A friend of mine recently linked to a story about stamp scrip currencies in a discussion about Initiative Q1. Stamp scrip currencies are an interesting monetary technology. They’re bank notes that require weekly or monthly stamps in order to be valid. These stamps cost money (normally a few percent of the face value of the note), which imposes a cost on holding the currency. This is supposed to encourage spending and spur economic activity.

This isn’t just theory. It actually happened. In the Austrian town of Wörgl, a scrip currency was used to great effect for several months during the Great Depression, leading to a sudden increase in employment, money for necessary public works, and a general reversal of fortunes that had, until that point, been quite dismal. Several other towns copied the experiment and saw similar gains, until the central bank stepped in and put a stop to the whole thing.

In the version of the story I’ve read, this is held up as an example of local adaptability and creativity crushed by centralization. The moral, I think, is that we should trust local institutions instead of central banks and be on the lookout for similar local currency strategies we could adopt.

If this is all true, it seems like stamp scrip currency (or some modern version of it, perhaps applying the stamps digitally) might be a good idea. Is this the case?

My first, cheeky reaction, is “we already have this now; it’s called inflation.” My second reaction is actually the same as my first one, but has an accompanying blog post. Thus.

Currency arrangements feel natural and unchanging, which can mislead modern readers when they’re thinking about currencies used in the 1930s. We’re very used to floating fiat currencies, that (in general) have a stable price level except for 1-3% inflation every year.

This wasn’t always the case! Historically, there was very little inflation. Currency was backed by gold at a stable ratio (there were 23.2 grains of gold in a US dollar from 1834 until 1934). For a long time, growth in global gold stocks roughly tracked total growth in economic activity, so there was no long-run inflation or deflation (short-run deflation did cause several recessions, until new gold finds bridged the gap in supply).

During the Great Depression, there was worldwide gold hoarding2. Countries saw their currency stocks decline or fail to keep up with the growth rate required for full economic activity (having a gold backed currency meant that the central bank had to decrease currency stocks whenever their gold stocks fell). Existing money increased in value, which meant people hoarded that too. The result was economic ruin.

In this context, a scrip currency accomplished two things. First, it immediately provided more money. The scrip currency was backed by the national currency of Austria, but it was probably using a fractional reserve system – each backing schilling might have been used to issue several stamp scrip schillings3. This meant that the town of Wörgl quickly had a lot more money circulating. Perhaps one of the best features of the scrip currency within the context of the Great Depression was that it was localized, which meant that it’s helpful effects didn’t diffuse.

(Of course, a central bank could have accomplished the same thing by printing vastly more money over a vastly larger area, but there was very little appetite for this among central banks during the Great Depression, much to everyone’s detriment. The localization of the scrip is only an advantage within the context of central banks failing to ensure adequate monetary growth; in a more normal environment, it would be a liability that prevented trade.)

Second to this, the stamp scrip currency provided an incentive to spend money.

Here’s one model of job loss in recessions: people (for whatever reason; deflation is just one cause) want to spend less money (economists call this “a decrease in aggregate demand”). Businesses see the falling demand and need to take action to cut wages or else become unprofitable. Now people generally exhibit “downward nominal wage rigidity” – they don’t like pay cuts.

Furthermore, individuals don’t realize that demand is down as quickly as businesses do. They hold out for jobs at the same wage rate. This leads to unemployment4.

Stamp scrip currencies increase aggregate demand by giving people an incentive to spend their money now.

Importantly, there’s nothing magic about the particular method you choose to do this. Central banks targeting 2% inflation year on year (and succeeding for once5) should be just as effective as scrip currencies charging 2% of the face value every year[^6]. As long as you’re charged some sort of fee for holding onto money, you’re going to want to spend it.

Central bank backed currencies are ultimately preferable when the central bank is getting things right, because they facilitate longer range commerce and trade, are administratively simpler (you don’t need to go buy stamps ever), and centralization allows for more sophisticated economic monitoring and price level targeting[^7].

Still, in situations where the central bank fails, stamp scrip currencies can be a useful temporary stopgap.

That said, I think a general caution is needed when thinking about situations like this. There are few times in economic history as different from the present day as the Great Depression. The very fact that there was unemployment north of 20% and many empty factories makes it miles away from the economic situation right now. I would suspect that radical interventions that were useful during the Great Depression might be useless or actively harmful right now, simply due to this difference in circumstances.

</figure>

[^6]: You might wonder if there’s some benefit to both. The answer, unfortunately, is no. Doubling them up should be roughly equivalent to just having higher inflation. There seems to be a natural rate of inflation that does a good job balancing people’s expectations for pay raises (and adequately reduces real wages in a recession) with the convenience of having stable money. Pushing inflation beyond this point can lead to a temporary increase in employment, by making labour relatively cheaper compared to other inputs.

The increase in employment ends when people adjust their expectations for raises to the new inflation rate and begin demanding increased salaries. Labour is no longer artificially cheap in real terms, so companies lay off some of the extra workers. You end up back where you started, but with inflation higher than it needs to be.

See also: “The Importance of Stable Money: Theory and Evidence” by Michael Bordo and Anna Schwartz.

[^7]: I suspect that if the stamp scrip currency had been allowed to go on for another decade or so, it would have had some sort of amusing monetary crisis.

-

My opinion is that their marketing structure is kind of cringey (my Facebook feed currently reminds me of all of the “Paul Allen is giving away his money” chain emails from the 90s and I have only myself to blame) and their monetary policy has two aims that could end up in conflict. On the other hand, it’s fun to watch the numbers go up and idly speculate about what you could do if it was worth anything. I would cautiously recommend Q ahead of lottery tickets but not ahead of saving for retirement. ↩

-

See “The Midas Paradox” by Scott Sumner for a more in-depth breakdown. You can also get an introduction to monetary theories of the business cycle on his blog, or listen to him talk about the Great Depression on Vimeo. ↩

-

The size of the effect talked about in the article suggests that one of three things had to be true: 1) the scrip currency was fractionally backed, 2) Wörgl had a huge bank account balance a few years into the recession, or 3) the amount of economic activity in the article is overstated. ↩

-

As long as inflation is happening like it should be, there won’t be protracted unemployment, because a slight decline in economic activity is quickly counteracted by a slightly decreased value of money (from the inflation). Note the word “nominal” up there. People are subject to something called a “money illusion”. They think in terms of prices and salaries expressed in dollar values, not in purchasing power values.

There was only a very brief recession after the dot com crash because it did nothing to affect the money supply. Inflation happened as expected and everything quickly corrected to almost full employment. On the other hand, the Great Depression lasted as long as it did because most countries were reluctant to leave the gold standard and so saw very little inflation. ↩ -

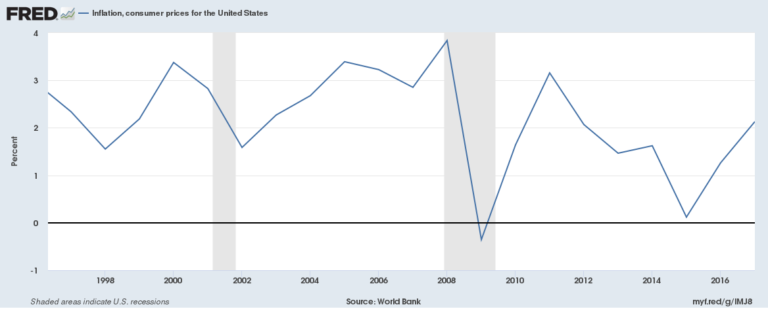

Here’s an interesting exercise. Look at this graph of US yearly inflation. Notice how inflation is noticeably higher in the years immediately preceding the Great Recession than it is in the years afterwards. Monetarist economists believe that the recession wouldn’t have lasted as long if it there hadn’t been such a long period of relatively low inflation.

As always, I'm a huge fan of the total lack of copyright on anything produced by the US government.