In simple economic theory, wages are supposed to act as signals. When wages increase in a sector, it should signal people that there’s lots of work to do there, incentivizing training that will be useful for that field, or causing people to change careers. On the flip side, when wages decrease, we should see a movement out of that sector.

This is all well and good. It explains why the United States has seen (over the past 45 years) little movement in the number of linguistics degrees, a precipitous falloff in library sciences degrees, some decrease in English degrees, and a large increase in engineering and business degrees1.

This might be the engineer in me, but I find things that are working properly boring. What I’m really interested in is when wage signals break down and are replaced by a job lottery.

Job lotteries exist whenever there are two tiers to a career. On one hand, you’ll have people making poverty wages and enduring horrendous conditions. On the other, you’ll see people with cushy wages, good job security, and (comparatively) reasonable hours. Job lotteries exist in the “junior doctor” system of the United Kingdom, in the academic system of most western countries, and teaching in Ontario (up until very recently). There’s probably a much less extreme version of this going on even in STEM jobs (in that many people go in thinking they’ll work for Google or the next big unicorn and end up building websites for the local chamber of commerce or writing internal tools for the company billing department2). A slightly different type of job lottery exists in industries where fame plays a big role: writing, acting, music, video games, and other creative endeavours.

Job lotteries are bad for two reasons. Compassionately, it’s really hard to see idealistic, bright, talented people endure terribly conditions all in the hope of something better, something that might never materialize. Economically, it’s bad when people spend a lot of time unemployed or underemployed because they’re hopeful they might someday get their dream job. Both of these reasons argue for us to do everything we can to dismantle job lotteries.

I do want to make a distinction between the first type of job lottery (doctors in the UK, professor, teachers), which is a property of how institutions have happened to evolve, and the second, which seems much more inherent to human nature. “I’ll just go with what I enjoy” is a very common media strategy that will tend to split artists (of all sorts) into a handful of mega-stars, a small group of people making a modest living, and a vast mass of hopefuls searching for their break. To fix this would require careful consideration and the building of many new institutions – projects I think we lack the political will and the know-how for.

The problems in the job market for professors, doctors, or teachers feel different. These professions don’t rely on tastemakers and network effects. There’s also no stark difference in skills that would imply discontinuous compensation. This doesn’t imply that skills are flat – just that they exist on a steady spectrum, which should imply that pay could reasonably follow a similar smooth distribution. In short, in all of these fields, we see problems that could be solved by tweaks to existing institutions.

I think institutional change is probably necessary because these job lotteries present a perfect storm of misdirection to our primate brains. That is to say (1) People are really bad at probability and (2) the price level for the highest earners suggests that lots of people should be entering the industry. Combined, this means that people will be fixated on the highest earners, without really understanding how unlikely that is to be them.

Two heuristics drive our inability to reason about probabilities: the representativeness heuristic (ignoring base rates and information about reliability in favour of what feels “representative”) and the availability heuristic (events that are easier to imagine or recall feel more likely). The combination of these heuristics means that people are uniquely sensitive to accounts of the luckiest members of a profession (especially if this is the social image the profession projects) and unable to correctly predict their own chances of reaching that desired outcome (because they can imagine how they will successfully persevere and make everything come out well).

Right now, you’re probably laughing to yourself, convinced that you would never make a mistake like this. Well let’s try an example.

Imagine a scenario is which only ten percent of current Ph. D students will get tenure (basically true). Now Ph. D students are quite bright and are incredibly aware of their long odds. Let’s say that if a student three years into a program makes a guess as to whether or not they’ll get a tenure track job offer, they’re correct 80% of the time. If a student tells you they think they’ll get a tenure track job offer, how likely do you think it is that they will? Stop reading right now and make a guess.

Seriously, make a guess.

This won’t work if you don’t try.

Okay, you can keep reading.

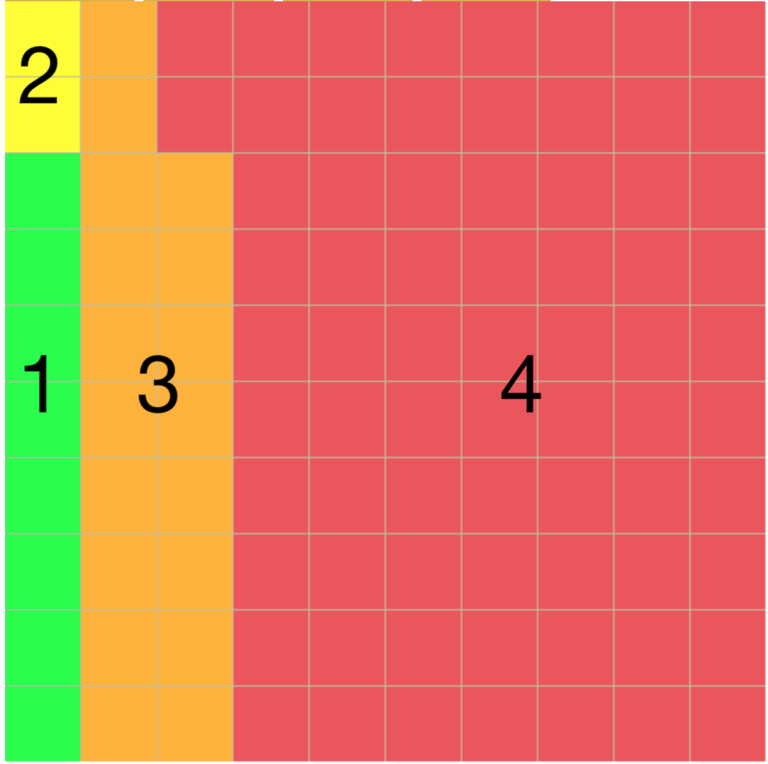

It is not 80%. It’s not even 50%. It’s 31%. This is probably best illustrated visually.

There are four things that can happen here (I’m going to conflate tenure track job offers with tenure out of a desire to stop typing “tenure track job offers”).

- A student can correctly believe they will get tenure

- A student can incorrectly believe they won't get tenure

- A student can incorrectly believe they will get tenure

- A student can correctly believe they won't get tenure

Ten students will get tenure. Of these ten, eight (0.8 x 10) will correctly believe they will get it (1/green) and two (10 – 0.8 x 10) will incorrectly believe they won’t (2/yellow). Ninety students won’t get tenure. Of these 90, 18 (90 – 0.8 x 90) will incorrectly believe they will get tenure (3/orange) and 72 (0.8 x 90) will correctly believe they won’t get tenure (4/red). Twenty-six students, those coloured green (1) and orange (3) believe they’ll get tenure. But we know that only eight of them really will – which works out to just below the 31% I gave above.

Almost no one can do this kind of reasoning, especially if they aren’t primed for a trick. The stories we build in our head about the future feel so solid that we ignore the base rate. We think that we’ll know if we’re going to make it. And even worse, we think that a feeling of “knowing” if we’ll make it provides good information. We think that relatively accurate predictors provide useful information against a small chance. They clearly don’t. When the base rate is small (here 10%), the base rate is the single greatest predictor of your chances.

But this situation doesn’t even require small chances for us to make mistakes. Imagine you had two choices: a career that leaves you feeling fulfilled 100% of the time, but is so competitive that you only have an 80% chance of getting into it (assume in the other 20%, you either starve or work a soul-crushing fast food job with negative fulfillment) or a career where you are 100% likely to get a job, but will only find it fulfilling 80% of the time.

Unless that last 20% of fulfillment is strongly super-linear34, or you don’t have any value at all on eating/avoiding McDrugery, it is better to take the guaranteed career. But many people looking at this probably rounded 80% to 100% – another known flaw in human reasoning. You can very easily have a job lottery even when the majority of people in a career are in the “better” tier of the job, because many entrants to the field will view “majority” as all and stick with it when they end up shafted.

Now, you might believe that these problems aren’t very serious, or that surely people making a decision as big as a college major or career would correct for them. But these fallacies date to the 70s! Many people still haven’t heard of them. And the studies that first identified them found them to be pretty much universal. Look, the CIA couldn’t even get people to do probability right. You think the average job seeker can? You think you can? Make a bunch of predictions for the next year and then talk with me when you know how calibrated (or uncalibrated) you are.

If we could believe that people would become better at probabilities, we could assume that job lotteries would take care of automatically. But I think it is clear that we cannot rely on that, so we must try and dismantle them directly. Unfortunately, there’s a reason many are this way; many of them have come about because current workers have stacked the deck in their own favour. This is really great for them, but really bad for the next group of people entering the workforce. I can’t help but believe that some of the instability faced by millennials is a consequence of past generations entrenching their benefits at our expense5. Others have come about because of poorly planned policies, bad enrolment caps, etc.

These cover the two ways we can deal with a job lottery, we can limit the supply indirectly (by making the job, or the perception of the job once you’ve “made it” worse), or limit the supply directly (by changing the credentials necessary of the job, or implementing other training caps) . In many of the examples of job lotteries I’ve found, limiting the supply directly might be a very effective way to deal with the problem.

I can make this claim because limiting supply directly has worked in the real world. Faced with a chronic 33% oversupply of teachers and soaring unemployment rates among teaching graduates, Ontario chose to cut in half the number of slots in teacher’s college and double the length of teacher’s college programs. No doubt this was annoying for the colleges, which made good money off of those largely doomed extraneous pupils, but it did lead to the end of the oversupply of teachers and a tighter job market for teachers and this was probably better for the economy compared to the counterfactual.

Why? Because having people who’ve completed four years of university do an extra year or two of schooling only to wait around and hope for a job is a real drag. They could be doing something productive with that time! The advantage of increasing gatekeeping around a job lottery and increasing it as early as possible is that you force people to go find something productive to do. It is much better for an economy to have hopeful proto-teachers who would in fact be professional resume submitters go into insurance, or real estate, or tutoring, or anything at all productive and commensurate with their education and skills.

There’s a cost here, of course. When you’re gatekeeping (for e.g. teacher’s college or medical school), you’re going to be working with lossy proxies for the thing you actually care about, which is performance in the eventual job. The lossier the proxy, the more you are needlessly depressing the quality of people who are allowed to do the job – which is a serious concern when you’re dealing with heart surgery – or the people providing foundational education to your next generation.

You can also find some cases where increasing selectiveness in an early stage doesn’t successfully force failed applicants to stop wasting their time and get on with their life. I was very briefly enrolled in a Ph. D program for biomedical engineering a few years back. Several professors I interviewed with while considering graduate school wanted to make sure I had no aspirations on medical school – because they were tired of their graduate students abandoning research as soon as their Ph. D was complete. For these students who didn’t make it into medical school after undergrad, a Ph. D was a ticket to another shot at getting in 6. Anecdotally, I’ve seen people who fail to get into medical school or optometry get a master’s degree, then try again.

Banning extra education before medical school cuts against the idea that people should be able to better themselves, or persevere to get to their dreams. It would be institutionally difficult. But I think that it would, in this case, probably be a net good.

There are other fields where limiting supply is rather harmful. Graduate students are very necessary for science. If we punitively limited their number, we might find a lot of valuable scientific progress falling to a stand-still. We could try and replace graduate students with a class of professional scientific assistants, but as long as the lottery for professorship is so appealing (for those who are successful), I bet we’d see a strong preference for Ph. D programs over professional assistantships.

These costs sometimes make it worth it to go right to the source of the job lottery, the salaries and benefits of people already employed7. Of course, this has its own downsides. In the case of doctors, high salaries and benefits are useful for making really clever applicants choose to go into medicine rather than engineering and law. For other jobs, there’s the problems of practicality and fairness.

First, it is very hard to get people to agree to wage or benefit cuts and it almost always results in lower morale – even if you have “sound macro-economic reasons” for it. In addition, many jobs with lotteries have them because of union action, not government action. There is no czar here to change everything. Second, people who got into those careers made those decisions based on the information they had at the time. It feels weird to say “we want people to behave more rationally in the job market, so by fiat we will change the salaries and benefits of people already there.” The economy sometimes accomplishes that on its own, but I do think that one of the roles of political economics is to decrease the capriciousness of the world, not increase it.

We can of course change the salaries and benefits only for new employees. But this somewhat confuses the signalling (for a long time, people will still have principle examples of the profession come from the earlier cohort). It also rarely alleviates a job lottery, because in practice people set this up for new employees to have reduced salaries and benefits for a time. Once they get seniority, they’ll expect to enjoy all the perks of seniority.

Adjunct professorships feel like a failed attempt to remove the job lottery for full professorships. Unfortunately, they’ve only worsened it, by giving people a toe-hold that makes them feel like they might someday claw their way up to full professorship. I feel that when it comes to professors, the only tenable thing to do is greatly reduce salaries (making them closer to the salary progression of mechanical engineers, rather than doctors), hire far more professors, cap graduate students wherever there is high under- and un- employment, and have more professional assistants who do short 2-year college courses. Of course, this is easy to say and much harder to do.

If these problems feel intractable and all the solutions feel like they have significant downsides, welcome to the pernicious world of job lotteries. When I thought of writing about them, coming up with solutions felt like by far the hardest part. There’s a complicated trade-off between proportionality, fairness, and freedom here.

Old fashioned economic theory held that the freer people were, the better off they would be. I think modern economists increasingly believe this is false. Is a world in which people are free to get very expensive training – despite very long odds for a job and cognitive biases that make understanding just how punishing the odds are – expensive training, in short, that they’d in expectation be better off without, a better one than a world where they can’t?

I increasingly believe that it isn’t. And I increasingly believe that having rough encounters with reality early on and having smooth salary gradients is important to prevent this world. Of course, this is easy for me to say. I’ve been very deliberate taking my skin out of job lotteries. I dropped out of graduate school. I write often and would like to someday make money off of writing, but I viscerally understand the odds of that happening, so I’ve been very careful to have a day job that I’m happy with8.

If you’re someone who has made the opposite trade, I’m very interested in hearing from you. What experiences do you have that I’m missing that allowed you to make that leap of faith?

And yes, I know there are many career opportunities for people holding those degrees and no I don’t think they’re useless. I simply think a long-term shift in labour market trends have made them relatively less attractive to people who view a degree as a path to prosperity.

-

I should mention that there’s a difference between economic value, normative/moral value, and social value and I am only talking about economic value here. I wouldn’t be writing a blog post if I didn’t think writing was important. I wouldn’t be learning French if I didn’t think learning other languages is a worthwhile endeavour. And I love libraries. ↩

-

That’s not to knock these jobs. I found my time building internal tools for an insurance company to be actually quite enjoyable. But it isn’t the fame and fortune that some bright-eyed kids go into computer science seeking. ↩

-

That is to say, that you enjoy each additional percentage of fulfillment at a multiple (greater than one) of the previous one. ↩

-

This almost certainly isn’t true, given that the marginal happiness curve for basically everything is logarithmic (it’s certainly true for money and I would be very surprised if it wasn’t true for everything else); people may enjoy a 20% fulfilling career twice as much as a 10% fulfilling career, but they’ll probably enjoy a 90% fulfilling career very slightly more than an 80% fulfilling career. ↩

-

It’s obvious that all of this applies especially to unions, which typically fight for seniority to matter quite a bit when it comes to job security and pay and do whatever they can to bid up wages, even if that hurts hiring. This is why young Canadians end up supporting unions in theory but avoiding them in practice. ↩

-

I really hope that this doesn’t catch on. If an increasing number of applicants to medical school already have graduate degrees, it will be increasingly hard for those with “merely” an undergraduate degree to get in to medical school. Suddenly we’ll be requiring students to do 11 years of potentially useless training, just so that they can start the multi-year training to be a doctor. This sort of arms race is the epitome of wasted time.

In many European countries, you can enter medical school right out of high school and this seems like the obviously correct thing to do vis a vis minimizing wasted time. ↩ -

The behaviour of Uber drivers shows job lotteries on a small scale. As Uber driver salaries rise, more people join and all drivers spend more time waiting around, doing nothing. In the long run (here meaning eight weeks), an increase in per-trip costs leads to no change whatsoever in take home pay.

The taxi medallion system that Uber has largely supplanted prevented this. It moved the job lottery one step further back, with getting the medallion becoming the primary hurdle, forcing those who couldn’t get one to go work elsewhere, but allowing taxi drivers to largely avoid dead times.

Uber could restrict supply, but it doesn’t want to and its customers certainly don’t want it to. Uber’s chronic driver oversupply (relative to a counterfactual where drivers waited around very little) is what allows it to react quickly during peak hours and ensure there’s always an Uber relatively close to where anyone would want to be picked up. ↩ -

I do think that I would currently be a much better writer if I’d instead tried to transition immediately to writing, rather than finding a career and writing on the side. Having a substantial safety net removes almost all of the urgency that I’d imagine I’d have if I was trying to live on (my non-existent) writing income.

There’s a flip side here too. I’ve spent all of zero minutes trying to monetize this blog or worrying about SEO, because I’m not interested in that and I have no need to. I also spend zero time fretting over popularizing anything I write (again, I don’t enjoy this). Having a security net makes this something I do largely for myself, which makes it entirely fun. ↩