Why do things happen the way they do?

Every day, there are conflicts between decision makers. These occur on the international scale (think the Cuban Missile Crisis), the provincial level (Ontario’s sex-ed curriculum anyone?) and the local level (Toronto’s bike lane kerfuffle). Conflict is inevitable. Understanding it, regrettably, is not.

The final results of many conflicts can look baffling from the outside. Why did the Soviet Union retreat in the Cuban missile crisis? Why do some laws pass and others die on the table?

The most powerful tool I have for understanding the ebb and flow of conflict is the Graph Model of Conflict Resolution (GMCR). I had the immense pleasure of learning about it under the tutelage of Professor Keith Hipel, one of its creators. Over the next few weeks, I’d like to share it with you.

GMCR is done in two stages, modelling and analysis.

Modelling

To model a problem, there are four steps:

- Select a point in time for the model

- Make a list of the players and their options

- Remove outcomes that don't make sense

- Create preference vectors for all players

The easiest way to understand this is to see it done.

Let’s look at the current nuclear stand-off on the Korean peninsula. I wrote this on Sunday, October 29th, 2017, so that’s the point in time we’ll use. To keep things from getting truly out of hand in our first example, let’s just focus on the US and North Korea (I’ll add in South Korea and China in a later post). What options does each side have?

US:

- Nuclear strike on North Korea

- Withdraw troops and normalize relations

- Status quo

North Korea:

- Invasion of South Korea

- Abandon nuclear program and submit to inspections

- Status quo

I went through a few iterations here. I originally wrote the US option “Nuclear strike” as “Pre-emptive strike”. I changed it to be more general. A nuclear strike could be pre-emptive, but it also could be in response to North Korea invading South Korea.

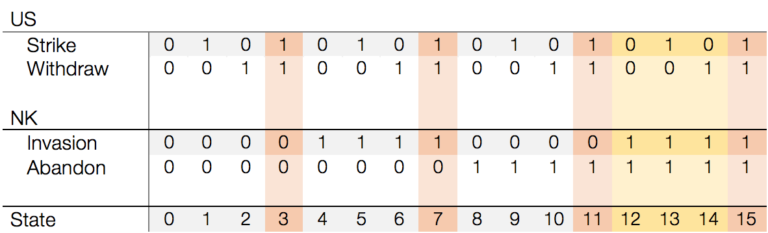

It’s pretty easy to make a chart of all these states:

If you treat each action that the belligerents can make as a binary variable (yes=1 or no=0), the states will have a natural ordering based off of the binary sum of the actions taken and not taken. This specific ordering isn’t mandatory – you can use any ordering scheme you want – but I find it useful.

You may also notice that “Status quo” appears nowhere on this chart. That’s an interesting consequence of how actions are represented in the GMCR. Status quo is simply neither striking nor withdrawing for the US, or neither invading nor abandoning their nuclear program for North Korea. Adding an extra row for it would just result in us having to do more work in the next step, where we remove states that can’t exist.

I’ve colour coded some of the cells to help with this step. Removing nonsensical outcomes always requires a bit of judgement. Here we aren’t removing any outcomes that are highly dispreferred. We are supposed to restrict ourselves solely to removing outcomes that seem like they could never ever happen.

To that end, I’ve highlighted all cases where America withdraws troops and strikes North Korea. I’m interpreting “withdraw” here to mean more than just withdrawing troops – I think it would mean that the US would be withdrawing all forms of protection to South Korea. Given that, it wouldn’t make sense for the US to get involved in a nuclear war with North Korea while all the while loudly proclaiming that they don’t care what happens on the Korean peninsula. Not even Nixon’s “madman” diplomacy could encompass that.

On the other hand, I don’t think it’s necessarily impossible for North Korea to give up its nuclear weapons program and invade South Korea. There are a number of gambits where this might make sense – for example, it might believe that if they attacked South Korea after renouncing nuclear weapons, China might back them or the US would be unable to respond with nuclear missiles. Ultimately, I think these should be left in.

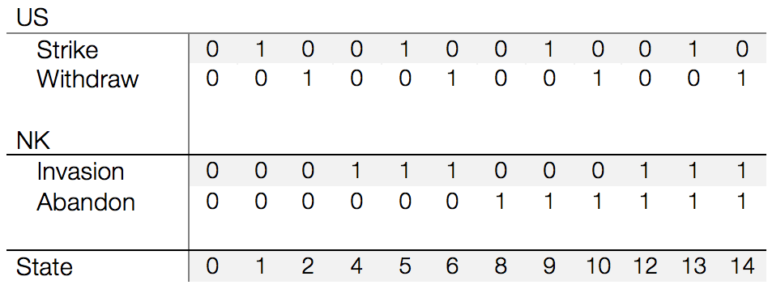

Here’s the revised state-space, with the twelve remaining states:

The next step is to figure out how each decision maker prioritizes the states. I’ve found it’s helpful at this point to tag each state with a short plain language explanation.

| State | Explantation |

|---|---|

| 0 | Status quo |

| 1 | Nuclear strike by the US, NK keeps nuclear weapons |

| 2 | Unilateral US troop withdrawal |

| 4 | North Korean invasion with only conventional US responses |

| 5 | North Korean invasion with US nuclear strike |

| 6 | US withdrawal and North Korean Invasion |

| 8 | Unilateral North Korean abandonment of nuclear weapons |

| 9 | US strike and North Korean abandonment of nuclear weapons |

| 10 | Coordinated US withdrawal and NK abandonment of nuclear weapons |

| 12 | NK invasion after abandoning nuclear weapons; conventional US response |

| 13 | NK invasion after abandoning nuclear weapons; US nuclear strike |

| 14 | US withdrawal paired with NK nuclear weapons abandonment and invasion |

While describing these, I’ve tried to avoid talking about causality. I didn’t describe s. 5 as “North Korean invasion in response to US nuclear strike” or “US nuclear strike in response to North Korean invasion”. Both of these are valid and would depend on which states preceded s. 5.

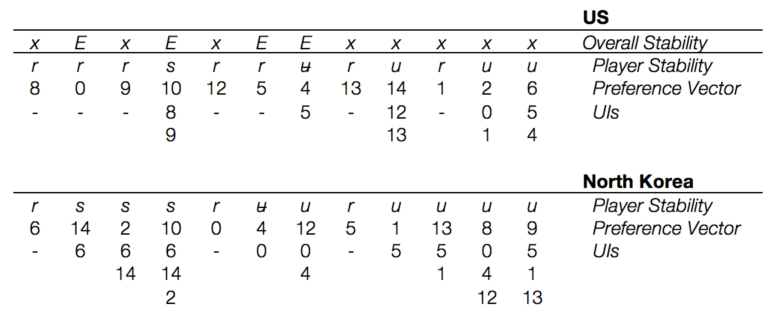

Looking at all of these states, here’s how I think both decision makers would order them (in order of most preferred to least preferred):

- US: 8, 0, 9, 10, 12, 5, 4, 13, 14, 1, 2, 6

- NK: 6, 14, 2, 10, 0, 4, 12, 5, 1, 13, 8, 9

The US prefers North Korea give up its nuclear program and wants to keep protecting South Korea. Its secondary objective is to seem like a reasonable actor on the world stage – which means that it has some preference against using pre-emptive strikes or nuclear weapons on non-nuclear states.

North Korea wants to unify the Korean peninsula under its banner, protect itself against regime change, and end the sanctions its nuclear program has brought. Based on the Agreed Framework, I do think Korea would be willing to give up nuclear weapons in exchange for a normalization of relations with the US and sanctions relief.

Once we have preference vectors, we’ve modelled the problem. Now it’s time for stability analysis.

Stability

A state is stable for a player if it isn’t advantageous for the player to shift states. A state is globally stable if it is not advantageous for any player to shift states. When a player can move to a state they prefer over the current state without any input from their opponent, this is a “unilateral improvement” (UI).

There are a variety of ways we can define “advantageous”, which lead to various definitions of stability:

Nash Stability (R): Stable if the actor has no unilateral improvements. States that are Nash stable tend to be pretty bad; these include both sides attacking in a nuclear war or both prisoners defecting in the prisoner’s dilemma. Nash stability ignores the concept of risk; it will never move to a less preferred state in the hopes of making it to a more preferred state.

General Metarationality (GMR): Stable if the actor has no unilateral improvements that aren’t sanctioned by unilateral moves by others. This tends to lead to less confusing results than Nash stability; Cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemma is stable in General Metarationality. General Metarationality accepts the existence of risk, but refuses to take any.

Symmetric Metarationality (SMR): Stable if an actor has no unilateral improvements that aren’t sanctioned by opponents’ unilateral moves after it has a chance to respond to them. This is equivalent to GMR, but with a chance to respond. Here we start to see the capacity to take on some risk.

Sequential Stability (SEQ): Stable if the actor has no unilateral improvements that aren’t sanctioned by opponents’ unilateral improvements. This basically assumes fairly reasonable opponents, the type who won’t cut off their nose to spite their face. Your mileage may vary as to how appropriate this assumption is. Like SMR, this system takes on some risk.

Limited Move Stability (LS): A state is stable if after N moves and countermoves (with both sides acting optimally), there exists no improvement. This is obviously fairly risky as any assumptions you make about your opponents’ optimal actions may turn out to be wrong (or wishful thinking).

Non-myopic Stability (NM): Equivalent to Ls with N set equal to infinity. This predicts stable states where there’s no improvements after any amount of posturing and state changes, as long as both players act entirely optimally.

The two stability metrics most important to the GMCR (at least as I was taught it) are Nash Stability (denoted with r) and Sequential Stability (denoted with s). These have the advantage of being simple enough to calculate by hand while still explaining most real-world equilibria quite well.

To do stability analysis, you write out the preference vectors of both sides, along with any unilateral improvements that they can make. You then use this to decide the stability of each state for each player. If both players are stable at a state by any of the chosen stability metrics, the state overall is stable. A state can also be stable if both players have unilateral improvements from it that result in both ending up in a dispreferred state if taken simultaneously. This is called simultaneous sanctioning and is denoted with u.

The choice of stability metrics will determine which states are stable. If you only use Nash stability, you’ll get a different result than if you combine Sequential Stability and Nash Stability.

Here’s the stability analysis for this conflict (using Nash Stability and Sequential Stability):

Before talking about the outcome, I want to mention a few things.

Look at s. 9 for the US. They prefer s. 8 to s. 9 and the two differ only on a US move. Despite this, s. 8 isn’t a unilateral improvement over s. 9 for the US. This system is called the Graph Model of Conflict Resolution for a reason. States can be viewed as nodes on a directed graph, which implies that some nodes may not have a connection. Or, to put it in simpler terms, some actions can’t be taken back. Once the US has launched a nuclear strike, it cannot un-launch it.

This holds less true for abandoning a nuclear program or withdrawing troops; both of those are fairly easy to undo (as we found out after the collapse of the Agreed Framework). Invasions on the other hand are in a tricky category. They’re somewhat reversible (you can stop and pull out), but the consequences linger. Ultimately I’ll call them reversible, but note that this is debatable and the analysis could change if you change this assumption.

In a perfect world, I’d go through this exercise four or five different times, each time with different assumptions about preferences or the reversibility of certain states or with different stability metrics and see how each factor changes the results. My next blog post will go through this in detail.

The other thing to note here is the existence of simultaneous sanctioning. Both sides have a UI from s. 4; NK to s. 0 and the US to s. 5. Unfortunately, if you take these together, you get s. 1, which both sides disprefer to s. 4. This means that once a war starts the US will be hesitant to launch a nuclear strike and North Korea would be hesitant to withdraw – in case they withdrew just as a strike happened. In reality, we get around double binds like this with negotiated truces – or unilateral ultimatums (e.g. “withdraw by 08:00 tomorrow or we will use nuclear weapons”).

There are four stable equilibria in this conflict:

- The status quo

- A coordinated US withdrawal of troops (but not a complete withdrawal of US interest) and North Korean renouncement of nuclear weapons

- All out conventional war on the Korean Peninsula

- All out nuclear war on the Korean Peninsula

I don’t think these equilibria are particularly controversial. The status quo has held for a long time, which would be impossible if it wasn’t a stable equilibrium. Meanwhile, s. 10 looks kind of similar to the Iran deal, with the US removing sanctions and doing some amount of normalization in exchange for the end of Iran’s nuclear program. State 5 is the worst-case scenario that we all know is possible.

Because we’re currently in a stable state, it seems unlikely that we’ll shift to one of the other states that could exist. In actuality, there are a few ways this could happen. A third party could intervene with its own preference vectors and shake up the equilibrium. For example, China could use the threat of economic sanctions (or the threat of ending economic sanctions) to try and get North Korea and the US to come to a détente. There also could be an error in judgement on the part of one of the parties. A false alarm could quickly turn into a very real conflict. It’s also possible that one party could mistake the others preferences, leading to them taking a course of action that they incorrectly believe isn’t sanctioned.

In future posts, I plan to show how these can all be taken into account, using the GMCR framework for Third Party Intervention and Coalitional Analysis, Strength of Preferences, and Hypergame Analysis.

Even without those additions, the GMCR is a powerful tool. I encourage you to try it out for other conflicts and see what the results are. I certainly found that the best way to really understand it was to run it a few times.

Note: I know it's hard to play around with the charts when they're embedded as images. You can see copyable versions of them here.