The following is the annotated speakers notes for a talk I gave on nuclear weapons today. I’d like to claim that it was a transcript, but after practicing from these notes for almost a week, I ended up giving the talk mostly ex tempore. Like I always do.

Note: The uncredited photos were created by the US government and therefore have no copyright attached. All other images are either original (and therefore covered by the same license as the rest of the blog) or are credited and subject to the original license (normally CC-BY of some sort).

Hi I’m Zach.

This will be a backwards explanation of nuclear weapons; I don’t have time to cover it all so instead of covering the boring stuff like how fission works, I’m going to talk about the strategic realities surrounding the use of nuclear weapons.

Let’s actually do this thing like you’re a bunch of kids; I’m going to assume you’re always asking me “why?”. So at the highest level: this is a presentation about nuclear weapons.

Why am I doing this?

Like maybe a lot of you, I’ve been worried about nuclear weapons of late. My worrying actually started in September 2016. I don’t know if you remember, but that was the first time it seemed like Trump might really win. And then I think a lot of us had to grapple with what that meant.

And the biggest question there was “could this mean the end of the world?”

I was worried about the end of the world because I knew Trump might end up with the nuclear launch codes and all I really knew about nuclear weapons was that they were really dangerous. At this point I was very much in the pop culture mode of “these are the things that end the world in blockbuster movies”.

Of course before I could really take this fear seriously, I had to think about why Trump might actually use nuclear weapons. Like I was pretty sure he wasn’t going to nuke Tuvalu just for fun.

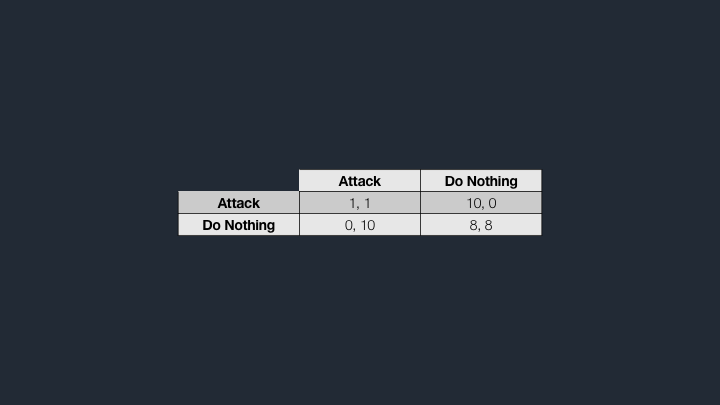

Here’s what the payoff matrix looks like for nuclear war between major powers. Everyone is pretty happy doing nothing, although they’d be happier if they could wipe out their pesky rivals1. Unfortunately, their rivals want to avenge themselves if they’re going to die.

The decision-making algorithm that tells us we’re going to stick to doing nothing is General Metarationality. We know how our opponents will act in response to our actions and we avoid actions that will cause strong sanctioning. And I don’t know of any sanctions stronger than getting nuked.

This whole thing works because everyone understands it. The logic is so inescapable and the probable actions of your enemies are so obvious that the whole edifice survives, even though doing nothing isn’t technically even the Nash equilibrium.

But this is just theory. How do you ensure mutually assured destruction in practice?

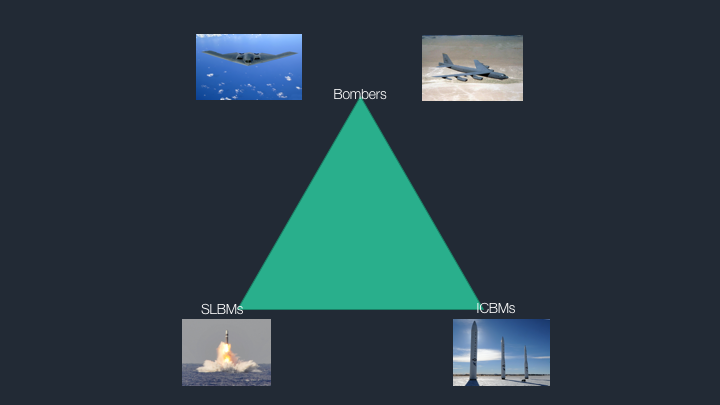

That’s a question people have been asking since the 1950s. By now everyone’s agreed that there’s a right way to do it and a wrong way to do it. The wrong way is to stick a bunch of missiles in a desert and call it a day. The right way is to come up with three separate ways of delivering your warheads, spend billions and billions of dollars on them, and call it a day.

Here we have the three methods that everyone’s chosen – and I want to make it clear that this is arbitrary; three others would work just as well2. As it stands though, the conventional nuclear triad is Nuclear armed bombers, like the US B-52 or B-2, Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) like the US Minuteman III, and submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), like the US Trident II. The idea with this triad is that it’s impossible for an enemy to launch a first strike so devastating that they take out your whole ability to respond.

Planners are always vaguely trying to build up their capacity for a “first strike” (remember the payoff matrix before; all nuclear powers would like it best if they could win a nuclear war). The first strike idea is this pernicious thought that maybe if you nuke someone else hard enough, you’ll take out all their nukes and just win. No one has ever felt confident in their ability to pull off a first strike, which is good because if someone ever was, nuclear war would become inevitable.

But why do we care about first strikes and MAD?

Because MAD has made civilization destroying nuclear war the default form of nuclear war, at least as far as all of the non-regional nuclear powers are concerned. With respect to Trump, it means that any nuclear war he starts with China or Russia, America’s traditional nuclear adversaries, would be really bad.

Now we all know that Trump is basically in Putin’s pocket. Because of this, I wasn’t very worried about a nuclear war with Russia; I always figured that if things got heated with Russia, Trump would fold.

At the time I first did this research – remember, this was September 2016, before we found out that Xi Jinping was more than a match for Trump – I thought nuclear war with China would become a lot more likely if Trump was president. So I looked into the Chinese nuclear arsenal and there I found the question that unlocked my understanding of nuclear weapons.

China’s premier missile is the silo-based Dongfeng 5. It has a range of about 12,000km and is tipped with a 5 Mt warhead.

A brief digression: when we talk about nuclear weapons and say “ton”, “kiloton”, or “megaton”, we’re referring to the explosion that would be created by a given mass of TNT. So, the warhead on the DF5 explodes with the same force as you’d expect from 5 million tonnes of TNT. Everyone always compares yields to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I hate this and think it’s stupid – for reasons I’ll get into in just one minute – but I’ll do it anyway. The DF5 releases 250 times as much energy as the 20 kt bomb that destroyed Nagasaki.

Anyway, the DF5 is 5Mt. The premier missile used by the US is the Trident II. It also has a range of 12,000km, it’s launched from a ballistic missile submarine, and it is armed with eight W88 warheads, each of which has a yield of 475kt.

And this was confusing, because we generally think of the US as more advanced than China when it comes to military technology – and here it definitely is! So why does China have bigger nukes?

That’s our key question right there.

So I just told you I hate the Hiroshima comparison. Here’s why: it assumes that nuclear weapons scale linearly. Get twice the yield and you should get twice the destruction, right? But very few things in the real world are linear. Nuclear weapons certainly aren’t.

There are actually 5 or 6 ways a nuclear weapon can kill you. There’s the shockwave, which knocks over buildings. There’s the gamma ray burst, which make death inevitable even as you appear to recover. There’s the thermal radiation, which can give you third degree burns, even if you’re kilometers distant. There’s the central fireball, which rips apart everything it touches. And then there’s the neutron burst and the X-rays and all the other ionizing radiation sources.

Each of these scales differently, but all of them are sublinear. This means that as a nuclear weapon gets bigger, it gets less efficient. The number of people you kill per additional ton of yield is much higher when your yield is 20kt than when it is 5Mt.

Some of these scaling effects are really complicated because of interactions with the ground or the air, but two are simple enough that I can give you a quick explanation of how to calculate them.

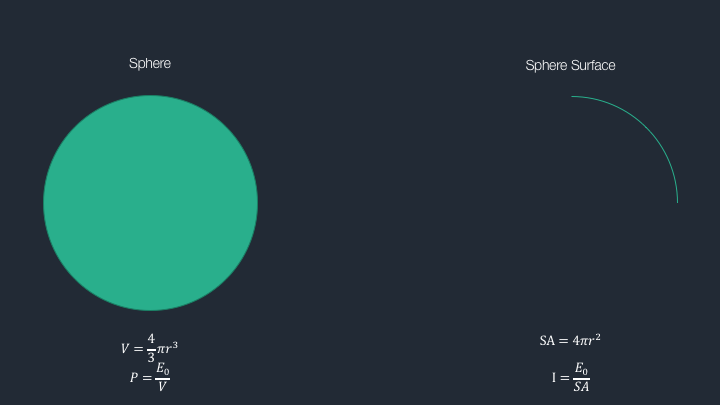

When it comes to shockwave, I want you to imagine a sphere. The amount of stuff in that sphere is proportional to the radius of that sphere, r, to the third power. Energy is just the capacity to do work, in this case, move stuff. If you want to figure out the amount of stuff energy can move – say move in a city destroying shockwave – you move this equation around a bit and you end up with the cube root of energy. To double the range of the shockwave, you need eight times as much energy.

For thermal radiation, I want you to think about the surface of a sphere. The size of the surface is proportional to r to the second power. Now we have a set amount of thermal radiation at the start that gets spread evenly around the whole surface of the sphere as flux, even as the sphere grows. So, you get ten meters out and the energy is spread out one hundred times as much as it was at one metre. You multiplied the radius by ten and saw the energy go down by a factor of one hundred. This also means that if you add in 100 times as much energy, the radius with a given flux will only grow ten-fold. The destructive radius (for any given destructive radiation effect) is proportional to the square root of the initial energy.

In both these cases, this means you’re facing severe diminishing returns. The 5 Mt Chinese warhead isn’t 10x as powerful as the 475kt American bomb. It’s between 2 and 3 times more powerful.

It gets worse for the Chinese warhead. It’s error radius is 800m, about 10x the 70m error radius of the Trident II. When aimed at a specific hardened target, like say a silo or a fortification, a target that needs to be hit with a certain amount of energy, the Chinese weapon is actually between 3x to 5x less likely to damage it than the American one, even though it’s much bigger. That’s not even to mention that there are eight American warheads on each missile.

They’re on these things called Multiple Independent Re-entry Vehicles, or MIRVs for short. Each one can pick its own target. Add all this up and the Trident II missile is something like 24x to 40x more dangerous than the DF5, despite looking less powerful at first glance.

The Chinese warhead is big because they haven’t mastered accuracy or MIRVs. With those, size matters much less.

24x or 40x or whatever is nice and all, but why doesn’t America go for broke and pack their thing full of 5 Mt warheads too? Wouldn’t that be best?

Well that’s because space and especially weight is at a premium on a rocket. The heavier it is, the shorter its range. There’s this whole laborious process called “miniaturization” that all nuclear weapons programs have to master. You detonate your test bomb in a big fixed installation, but then you need to make it small enough that you can fit it on a missile. That’s hard.

If you look at the real experts – not the pundits on CNN, but the brilliant folks at 38North or Ploughshares – you’ll see that there’s a lot of anxiety about North Korea “miniaturizing” their nuclear weapons. Jong-un say they have. We don’t know if he’s telling the truth or not. Miniaturization is the difference between some scary seismic readings and a crater where Tokyo used to be. If North Korea can get their physics package (the nuke part of the warhead) down to 400, 500kg, then they’ll have room to put on a heat shield. Then they’ll have an ICBM.

Not a triad. So, there’s still time for a first strike. But they’re working on SLBMs. Soon, maybe in a decade, they’ll be a “real” nuclear power. That’s bad for the US. But it’s really bad for China. Right now, China is actually more at risk from North Korea than the US, according to many analysts. It’s actually gotten so bad that China has set up missile defenses between North Korea and Beijing.

These probably won’t work if push comes to shove, but that’s a story for another day.

So to summarize:

- The major nuclear powers are China, Russia, and the USA

- Mutually Assured Destruction is guaranteed by a nuclear triad and has kept these powers from nuking each other.

- As long as the triad lasts, first strikes will bring massive retaliation

- Retaliation means that you have to do a certain amount of damage to certain targets. You can achieve this with really big nukes, or really precise nukes.

- Scaling means that 10x the yield does not bring 10x the destructive power. Conversely, accuracy gives a lot of bang for your buck. 10x accuracy means 100x or 1000x damage to a specific target.

- Don't use Hiroshima as a unit of measure, because people will assume that destruction is linear and overestimate how bad things will be

- North Korea can't do anything until they miniaturize a nuke. It's unclear if they have yet.

If you want to learn more, either about nuclear weapons in general or North Korea’s nuclear weapon program in particular, you can go to my blog at socraticfm.com. Also Wikipedia exists.

Questions

- In response to a question about the risk of Pakistani nuclear weapons falling into the wrong hands, I explained that this would be locally really bad, but drew the distinction between events that are bad for a localized group of people (like the Taliban nuking Karachi) and events that are bad for the human race (a MAD-level nuclear exchange between China and the US). If you're worrying about the existential risk posed by nuclear weapons, the first is really just noise, except insofar as it can make the second more likely by increasing tensions all around.

- In response to a question about disarmament, I talked about the New START treaty and the need to distinguish between warheads that are stored (most of them, at least for Russia and America) and warheads ready to go (1,550 for both the US and Russia, if they're sticking to their treaty obligations). I stressed the need for further treaties like New START to slowly reduce the number of active (and therefore existentially dangerous) nuclear weapons in the arsenals of major powers.

Using this presentation

The slides are available here. This content, like everything else original on my blog, is covered by the CC-BY-NC-SA v4 International license. If you present this, please reference this blog and include a link. If you are a student and using this presentation is against the academic policies of your institution, I’d ask that you please refrain from plagiarizing it.

-

I was questioned pretty heavily on this pay-off matrix. Several people thought that Do Nothing should be preferred to Attack. I have two things to say to this:

First, in an iterated game with this sort of matrix, the highest payoff comes when people cooperate the most. So while at any given point in time attacking might be preferred, once you take into account that real life is iterated, doing nothing is a better long term strategy.

Second, all of us born after the Cold War, or even born after the 60s, cannot adequately understand what it was like to live in a world where it really did seem like the Soviets might “bury us”. Faced with that kind of existential threat, a first strike seemed like an appealing option. In this globalist age, it does seem much worse to launch a first strike, especially because major powers do major mutual trade. ↩ -

If questioned here, I was going to mention carrier based bombers (France tried this for a while) and nuclear tipped cruise missiles (the US may move in this direction). ↩