When I write about economics on this blog, it is quite often from the perspective of monetary economics. I’ve certainly made no secret about how important monetary economics is to my thinking, but I also have never clearly laid out the arguments that convinced me of monetarism, let alone explained its central theories. This isn’t by design. I’ve found it frustrating that many of my explanations of monetarism are relegated to disjointed footnotes. There’s almost an introduction to monetarism already on this blog, if you’re willing to piece together thirty footnotes on ten different posts.

It is obviously the case that no one wants to do this. Therefore, I’d like to try something else: a succinct explanation of monetary economics, written as clearly as possible and without any simplifying omissions or obfuscations, but free of (unexplained) jargon.

It is my hope that having recently struggled to shove this material into my own head, I’m well positioned to explain it. I especially hope to explain it to people broadly similar to me: people who are vaguely left-leaning and interested in economics as it pertains to public policy, especially people who believe that public policy should have as its principled aim ensuring a comfortable and dignified standard of living for as many as possible (especially those who have traditionally been underserved or abandoned by the government).

To begin, I should define monetarism. Monetarism is the branch of (macro-)economic thought that holds that the supply of money is a key determinant of recessions, depressions, and growth (in whole, the “business cycle”, the pattern of boom and bust that characterizes all market economies that use money).

Why does money matter?

In general, during both periods of growth and recessions, the supply of money increases. However, there have been several periods of time in America where the supply of money has decreased. Between the years of 1867 and 1963, there were eight such periods. They are: 1873-1879, 1892-1894, 1907-1908, 1920-1921, 1929-1933, 1937-1938, 1948-1949, and 1959-1960.

When I first read those dates, I got chills. Those are the dates of every single serious contraction in the covered years.

Furthermore, while minor recessions aren’t characterized by a decrease in the supply of money, they are characterized by a decrease in the rate of the growth of the money supply. That is to saw, the money supply is still increasing, but by less than it normally does.

Let’s pause for a second and talk about the growth of the money supply. Why does it normally grow?

Under the international gold standard, which existed in modern times under one form or another until President Nixon de facto ended it in 1971, money either existed as precious metal coins (specie), or paper banknotes backed by specie. If you had a dollar in your wallet, you could convert it to a set amount of gold.

As long as gold mining was economically viable (it was in the period covering 1867-1963, which we’re talking about), there was, in general, steady growth in the money supply. Each dollar’s worth of gold pulled out of the ground made it possible to expand the monetary supply by a similar amount, although I should note that not all gold that was mined was used this way (some was used, for example, to make jewelry).

Since the end of the gold standard, governments have made a commitment to keeping the money supply steadily increasing. We commonly refer to this as “printing money”, but that’s a bit of an anachronism. Central banks create money by buying assets (like government debt) using money that did not previously exist. This process is digital1.

(We call currencies that aren’t backed by precious metals or other commodities “fiat” currencies, because their value exists, at least in part, because of government fiat.)

In both fiat and commodity currency regimes, there is a clear correlation between changes in the growth rate of the money supply and the growth rate of the economy. A decrease in money supply growth leads to a recession. An outright decrease in money supply (i.e. negative growth) leads to a depression. Even within the categories (depression and recession), there’s a correlation. The worse the decline in growth rate, the worse the downturn.

Whenever someone provides an interesting correlation, it is important to ask about causation. It does not necessarily need to be the case that a decrease in money supply is what is causing recessions. It could instead be that recessions cause the decrease in the rate of money growth, or that money supply is a lagging indicator of recessions (as unemployment is), rather than a leading one2.

There are four reasons to suspect that money is in fact the causal factor in business cycles.

First, there is the simple fact that history suggests a causal relationship. We do not see any history of central banks (which remember, help control the money supply) reacting to economic recession with plans to cut the supply of money. On the other hand, we have seen recessions which were started when central banks have deliberately decreased the growth of the money supply, as the Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker did in 1980.

Second, it is possible to do correlational analyses to determine if it is more probable that something is a leading or lagging indicator. Anna Schwartz and Milton Friedman did just such an analysis on data from US recessions and depressions between 1867 and 1963 and found correlation only with money as a leading indicator.

Third, money is much better positioned to explain recessions and depressions than the alternative (Keynesian) theory which holds that recessions occur due to a fall in investment. The correlation between the amount of investment and the amount of economic growth in America (again, between 1867 and 1963) disappears when you control for changes in the money supply. The correlation between money and growth remains, even when controlling for investment.

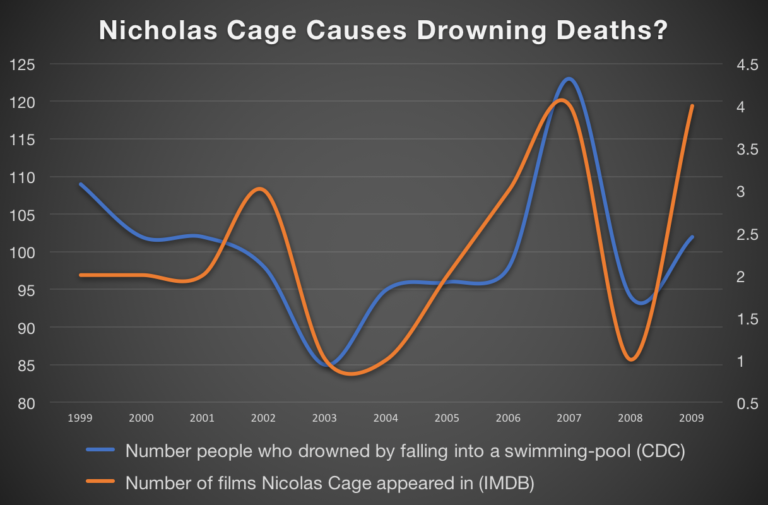

Fourth, we do not need to be a priori skeptical of money as a key determinant of the business cycle. Money is clearly linked to the economy; it literally permeates it. The business cycle of growth followed by recession is observed only in economies that use money3. While it would make sense to be inherently skeptical of a theory that holds that recessions occur when not enough sewing needles are produced, we need to be much less reflexively skeptical of money. Claiming money causes the business cycle isn’t like claiming Nicholas Cage movies cause accidental drowning.

These arguments are necessarily summaries; this blog post isn’t the best place to put all of the graphs and regression analyses that Schwartz and Friedman did when first formulating their theory of monetary economics. I’ve read through the analysis several times and I believe it to be sound. If you wish to pore over regressions yourself, I recommend the paper Money and Business Cycle (1963).

If you can accept that the supply of money plays a key role in the business cycle, you’ll probably find yourself in possession of several questions, not the least of which will be “how?”. That’s a good question! But before I can explain “how”, I first need to define money, explain how banking works, and delve into the role and abilities of the central bank. It will be worth it, I promise.

What is money?

At first blush, this is a silly question. Money is one of those things we know when we see. It’s the cash in our wallets and the accounts at our banks. Except, it’s not quite that.

Money isn’t a binary category. Things can have varying amounts of “moneyness”, which is to say, can be varyingly good at accomplishing the three functions of money. These three functions are: a store of value (something that can be exchanged for goods in the future), a unit of account (something that you can use to keep track of how many goods you could buy), and a medium of exchange (something that you can give to someone in exchange for goods).

While bank deposits and cash are obviously money, there are also a variety of financial products that we tend to consider money even though they have less moneyness than cash. For example, robo-investment accounts (of the sort that my generation uses) often given the illusion of containing cash by being denominated in dollars and allowing withdrawals4. What makes them have less moneyness than cash is only apparent when you look under the hood and realize they contain a mixture of stocks and loans.

In a monetary context, when we say “money”, we aren’t referring to investment accounts or any other instrument that pretends to be cash5. Instead, we’re referring to the “money supply”, which is made up of instruments with very high moneyness and is determined by three factors:

- The monetary base. This is the money that the central bank issues. We see it as cash, as well as the reserves that regular banks choose to hold.

- The amount of reserves banks keep against deposits. Later this will show up as the deposit-reserve ratio, which is calculated by dividing total deposits by the reserves kept on hand by banks.

- How much of its currency the public chooses to deposit at banks. This will surface later as the deposit-currency ratio. This is calculated by dividing the value of all deposit accounts at banks by the total amount of currency in circulation.

What are reserves?

When you give your money to a bank, it doesn’t hold all of it in a vault somewhere. Vaults are expensive, as are guards, tellers, and account software. If banks held onto all of your cash for you, you’d have to pay them quite a lot of money for the service. Many of us would decide it’s not worth the bother and keep our cash under the proverbial mattress.

Banks realized this a long time ago. They responded like any good business – by finding a way to cut costs for the consumer.

Banks were able to cut costs by realizing that it is very rare for everyone to want all of their money back at once. If banks didn’t need to keep all of the deposited cash (or, in the olden days, gold and silver specie) on hand, they could lend some of it out and use the interest it earned to subsidize the cost of running the bank.

This led to the birth of the fractional reserve system, so named because bank reserves are a fraction of the money deposited in banks6.

Once you have a fractional reserve system, a funny thing happens with the money supply: it is no longer made up solely by money created by the central bank. When commercial banks lend out money that people have deposited, they essentially create money. This is how the money supply ends up depending on the deposit-reserve ratio; this ratio describes how much money banks are creating.

When banks decide to lend out more of their reserves, the deposit-reserve ratio increases and the money supply increases. When banks instead decide to lend out less and sit on their cash, the deposit-reserve ratio decreases and the money supply decreases.

But it isn’t just the banks that get a vote in the money supply under a fractional reserve system. Each of us with a bank account also gets a vote. If we trust banks or if we’re enticed by a high interest rate, we hold less cash and put more money in our bank accounts (which causes the deposit-currency ratio – and therefore the money supply – to increase). If we’re instead worried about the stability of banks or if bank accounts aren’t paying very appealing interest rates, we’ll tend to hold onto our cash (decreasing the deposit-currency ratio and the total supply of money).

Holding the deposit-reserve ratio constant, the money supply increases when the deposit-currency ratio increases and decreases when the deposit-currency ratio decreases. This is because every dollar in the bank becomes, via the magic of fractional reserve banking, more than a single dollar in the money supply. Your deposit remains available to you, but most of it is also lend out to someone else.

While we cannot in practice hold any ratio constant, there do exist real constraints on the deposit-reserve ratio. In the US, there are laws that require banks above a certain size to keep liquid reserves equal to at least 10% of their deposits. Many other countries lack reserve requirements per se, but do require banks to limit how leveraged they become, which acts as a de facto limit on their deposit-reserve ratio7.

It isn’t just the government that provides restraints. Banks may have internal policies that require them to have lower (safer) deposit-reserve ratios the government demands.

Governments and bank risk management departs set limits on the deposit-reserve ratio in an attempt to limit bank failures, which become more likely the higher the deposit-reserve ratio gets. Banks don’t really sit on all of their reserves, or even stuff it in vaults. Instead, they normally use it to buy assets that they and the government agree are safe. Often this takes the form of government bonds, but sometimes other assets are considered suitable. Many of the mortgage backed securities that exploded during the financial crisis were considered suitably safe, which was a major failure of the ratings agencies.

If assets banks have bought to act as their reserves lose value, they can find their deposit-reserve ratio higher than they want it to be, which often results in a sudden decline in loan activity (and therefore a decline in the growth rate of the money supply) as they try to return their financials to normal8. Bank failures can occur if deposit-reserve ratios get so far from normal that banks cannot afford to meet normal withdrawal requests.

If people and banks have so much control over the money supply, what do central banks do?

What central banks do depends on their mandate; what the government has told them to do. The US Federal Reserve Bank has a dual mandate: to maintain a stable price level (here defined as inflation of approximately 2%) and to ensure full employment (defined as an unemployment rate of around 4.5%9). The Fed is actually a bit of an aberration here. Many central banks (like Canada’s) have a single mandate: “to keep inflation low, predictable, and stable”.

Currently, central banks achieve their mandate by manipulating interest rates. They do this with a “target rate” and “open market operations”. The target rate is the thing you hear about on TV and in the news. It’s where the central bank would like interest rates to be (here, interest rates really means “the rate at which banks lend each other money”; consumers can generally expect to make less interest on their savings and pay more when they take out loans10).

Note that I’ve said the target rate is where the central bank would “like” interest rates to be. It can’t just call up every bank and declare the new interest rate by fiat. Instead, it engages in those “open market operations” that I mentioned. There are two types of open market operations.

When the interest rate is above target, the central bank lends money to banks at below-market interest rates (to increase the supply of money and encourage interest rates to become lower). When the interest rate is below target, the central bank will begin selling assets to banks (to give banks something else to do with their money and thereby make them demand more interest from each other when loaning).

Open market operations are normally fairly successful at keeping the interest rate reasonably close to the target rate.

Unfortunately, the target rate is only moderately effective at achieving monetary policy goals.

Remember, the correlation we identified in the first section is for the total supply of money, not for the interest rate. There’s some correlation between the two (lower interest rates can mean a fast monetary growth rate), but it isn’t exact.

When you hear people on TV say that “low interest rates mean easy money” (“easy money” means variously “high growth in the money supply” or “growth in the money supply likely to cause above-target inflation”) or “high interest rates mean tight money” (a shrinking money supply; below target inflation), you are hearing people who don’t entirely understand what they’re talking about.

The key piece of information reporters often lack is how much demand banks have for money. If banks don’t really want much more money (perhaps because the economy is tanking and there’s nothing to do with money that will justify loan repayments) then a low interest rate can still result in the money supply barely growing. It may be that the central bank target rate is quite low by historical standards (say 1%) but still not low enough to expand the money supply via loans to banks.

Put another way, while a 1% interest rate is always easier than a 2% interest rate, there’s often nothing to tell a priori if it represents easy money, which is to say, growth in the money stock. A 1% target rate can be contractionary (shrink the money stock) if banks won’t take out loans when charged it.

Conversely, a 10% interest rate could conceivably represent easy money if banks are still taking out lots of loans at that rate. Take a case where there’s some asset currently returning 20% every year. Under those circumstances, 10% interest payments are a steal and the money supply would continue to increase. It’s certainly tighter money than a 2% interest rate, but it’s not always tight money.

If you want to see if the target interest rate is inflationary or deflationary, you should look at the market’s expectations for inflation. If the market is predicting higher than target inflation, money is easy. If it’s predicting below target inflation, money is tight.

Central banks often collect statistics so that they can judge the effectiveness of their policy actions. If inflation is too low, they’ll lower their target rate. Too high, and they’ll raise it. Over time, if the economy is stable, central banks will correct any short run problems introduced by interest rate targeting and eventually zero in on their inflation target. Unfortunately, this leaves the door open to painful short-term failures.

How do central banks fail in the short run?

First, I want to make it clear that short-term failures are bad. While long-term price stability is definitely a good thing, short-term fluctuations in the money supply can lead to recessions (remember our solid correlation between shrinking money supply and recessions). Even relatively minor short-term failures can have consequences for hundreds of thousands or millions of people whenever recessions lead to job losses.

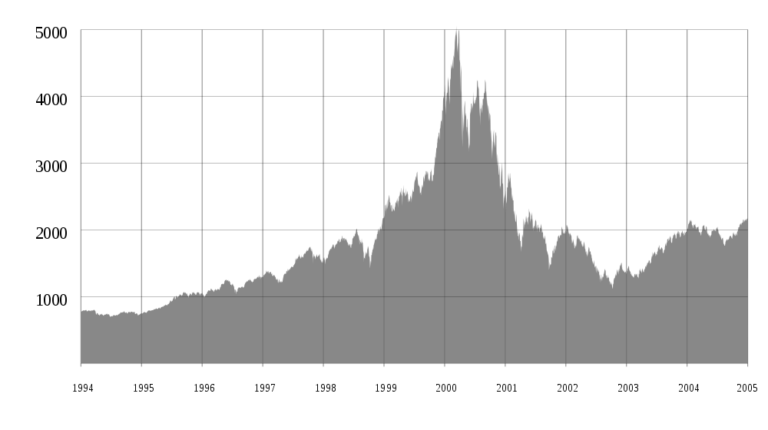

Central banks most commonly fail in the short-run because of some sort of unexpected shock. Most commonly, shocks that lead to long recessions originate in the financial sector. The 2001 dot-com crash, for example, didn’t technically lead to a recession in the United States, despite the huge stock market losses11.

Shocks to the financial sector are unusually likely to cause recessions because of the key role that the financial sector plays in determining the monetary supply (via the deposit-reserve ratio we discussed above), as well as the key role that confidence in the financial sector plays (via the deposit-currency ratio).

When financial institutions run into trouble, they have to scramble for liquidity – for cash that they can have on hand in case people wish to withdraw their money12 – which means they make fewer loans. Suddenly, the money multiplier that banks supply shrinks and the amount of money in the economy decreases.

Things can get even worse when the public loses faith in the banking system. If you suspect that a bank might fail, you will want to get your money out while you still can. Unfortunately, if everyone comes to believe this, then the bank will fail13. By design, it doesn’t have enough cash on hand to pay everyone back14. When this happens, it is called a “run” on the banks or a “bank run” and they’re thankfully becoming more and more rare. Many developed countries have ended them entirely with a program of deposit insurance. That’s the stickers you see on the door of your bank that promises your deposits will be returned to you, even if the bank fails15.

It’s good that we’ve stopped bank runs, because they’re incredibly deflationary (they are very good at shrinking the money supply). This is due to the deposit-currency ratio being a key determinant of the total money supply. When people stop using banks, the deposit-currency ratio falls and the money supply decreases.

Since bank failures can occur quite suddenly and can spread throughout the financial system quickly, a financial crisis can cause a deflation that is too rapid for the central bank to react too. This is especially true because modern central banks have a general tendency to fear inflation much more than many monetarists believe they should16. This is really unfortunate! A slow response to a decrease in the growth of the money supply (whether caused by a financial crisis or something else) can easily turn into a recession or depression, with all the attendant misery.

Okay, but can you explain how this happens?

Many individuals and companies like to keep a certain amount of money on hand, if at all possible. When they have less money than this, they economize, until they feel comfortable with the amount of money they have. When they have more money, the tend to invest it or spend it.

When the money supply increases, either via by the central bank buying bonds, the government reducing reserve requirements, or people deciding to hold more of their money at banks, there are suddenly larger supplies of money at banks then they would like to hold on to.

Banks then spend this money (or invest it, which is essentially giving it to someone else to spend). The people banks give the money to immediately face the same problem; they have more money than they plan on holding. What follows is a game of hot potato, as everyone in the economy tries to keep their account balances where they want them (by spending money).

If there is free capacity in the economy (e.g. factories are idle, people are unemployed, etc.), then this free capacity eventually absorbs the money (that is to say: people who had less money on hand then they desired are quite happy to grab and hold onto the extra money). If there is very little free capacity in the economy however (i.e. unemployment is low, production high), then this money really cannot be spent to produce anything extra. Instead, we have more money, chasing the same amount of goods and services. The end result of that is prices increasing – what we call inflation – or, just as correctly, money becoming worth less.

Once prices rise, people realize they need to hold onto slightly more money and a new equilibrium is reached.

After all, the money that people are holding onto is really acting as a unit of account. It denotes how many days (or weeks, or months) of consumption they want to have easy access to. Inflation changes how much money you need to hold onto to keep the same number of days (weeks, months) of production17.

Now, let’s run this whole thing in reverse. Instead of increasing the supply of money, the money supply is decreasing (or failing to grow at the expected rate). Maybe there were new reserve requirements, or a financial crash, or the central bank misjudged the amount of money it needed to create18. Regardless of how it happens, someone who was expecting to get some money isn’t going to get it.

This person (bank, corporation) will find themself having less cash on hand then they hoped for and will cut back on their spending. This spending was going to someone else who was hoping for it. And suddenly the whole economy is trying to collectively spend less money, which it can’t do right away.

Instead, money becomes relatively more valuable as everyone scrambles for it. This looks like prices going down.

The price of labour (wages), might, in theory be expected to go down, but in practice it doesn’t. It’s very emotionally taxing to try and convince many employees to accept pay cuts (in addition to being bad for morale), so firms tend to prefer pay freezes, cutting back on contract labour, switching some workers to part-time, and firings to pay cuts19.

Decreased growth in the rate of money affects more than just workers. Factories close or sit idle. Economic capacity diminishes. Ultimately, the whole economy can spend less, if some of the economy is gone.

All of these taken together are the hallmarks of recession. We see job losses, idle capacity, and closures. And we can directly point at failures of central bank policy as the culprit.

Can changes in the growth rate of money affect anything else?

There are three interesting relationships between inflation and employment.

First, it seems that higher than expected inflation leads to increased employment. Friedman and Schwartz speculated that this occurs because corporations are better positioned to see inflation than workers. When they see evidence of inflation, they can quickly hire workers at previously normal salaries. These salaries represent something of a discount when there’s unexpected inflation, so it’s quite a steal for the companies.

Unfortunately, this effect doesn’t persist. As soon as everyone understands that inflation has increased, they bake this into their expectations of salaries and raises. Labour stops being artificially cheap, and companies may end up letting go of some of the newly hired workers.

Second, it seems that increasing money supply is correlated with increasing real wages, that is, wages that are already adjusted for inflation. While it makes sense that inflation will lead to an increase in nominal wages (that is, inflation leads to higher salaries, even if those salaries cannot buy anything extra), it’s a bit odder that it leads to higher real wages. I haven’t yet seen an explanation for why this is true, but it’s an interesting tidbit and one I hope to understand better in the future20.

Finally, inflation can play an important role in avoiding job losses. Not all economic downturns are caused by central banks. Sometimes, the shock is external (like an earthquake, commodity crash, or a trade embargo). In these cases, certain sectors of the economy may be facing losses and may respond with firing (as we saw above, wage cuts are rarely considered a tenable option). However, inflation can act as an implicit wage cut and stop job losses long enough for the economy to adjust.

If salaries are kept constant while inflation continues apace (or even increases), they become relatively less expensive, all without the emotional toll that wage cuts take. This can protect jobs and engineer a “soft landing”, where a shock doesn’t lead to any large-scale job losses.

Obviously, this has to be temporary, so as not to erode the purchasing power of workers too much, but most shocks are temporary, so this is not a difficult constraint.

Okay, what does this say about policy?

There are three main policy takeaways from this post.

First, interest rates are a bad policy indicator. It’s hard for people to break their association between easy money and low interest rates, which means monetary policy is likely to end up too tight. The best analogy I’ve heard for interest rates are a steering wheel that sometimes points a bus left when turned left and sometimes points the bus left when turned right. If you wouldn’t get in a bus driven like that, you shouldn’t be thrilled about being in an economy that’s being driven in the exact same way.

Second, a stable monetary policy is very useful. Note that stable monetary policy implies neither stable interest rates, nor stable inflation. Rather, a stable monetary policy means that everyone can have confidence that the central bank will act in predictable and productive ways. Stable monetary policy smooths out the peaks and valleys of the business cycle. It stops highs from becoming too speculative and keeps lows from leading to terrible grinding unemployment. It also lets unions and workers bargain for long-term wage increases and allows companies to grant them without being scared they’ll become unsustainable due to below-target inflation.

Third, expectations are a powerful tool. If banks believe that the central bank will print lots of money (and buy lots of assets) during a crisis, they won’t have to stop making loans, or increase their reserves. Sometimes, the mere expectation of a forceful government intervention prevents any need for the intervention (like with deposit insurance; it rarely pays out because its existence has drastically reduced the need for it). Had the Federal Reserve reacted more aggressively to the financial crisis, it may have been possible to avoid the massive bailout to financial companies.

I know that “the money supply” will never be a progressive priority. But I think it’s a thing that progressives should care about. Billionaires may not like bad monetary policy, but they aren’t the ones who feel the brunt of its failure. Those are the workers who are laid off, or the pensioners who lose their savings.

I hope I’ve made the case that in order to care about them, we need to care about how money works.

Further Reading and Sources

I drew heavily on Money in Historical Perspective, by Anna J. Schwartz when writing this blog post. The papers Money and Business Cycles (1963, with Milton Friedman), Why Money Matters (1969), The Importance of Stable Money: Theory and Evidence (1983, with Michael D. Bordo), and Real and Pseudo-Financial Crises (1986) were particularly informative.

Scott Sumner’s blog The Money Illusion is an excellent resource for current monetarist thought, while J. P. Koning’s blog Moneyness provides many excellent historical anecdotes about money.

Like all of my posts about economics, this one contains way too many footnotes. These footnotes are mainly clarifying anecdotes, definitions, and comments. I've relegated them here because they aren't necessary for understanding this post, but I think they still can be useful.

-

Separately, banks create currency for day to day use based on the public’s demand for currency. The more you go to the ATM, the more bills the central bank creates for you to withdraw. Banks return currency to the central bank every so often (either to buy assets the central bank holds, or to replace it with its digital equivalents). If fewer people want cash and ATMs are overprovisioned, banks will deposit more cash with the central bank than they, as a whole, withdraw.

Therefore, while the central bank controls the growth of the money supply, the public collectively determines the growth in the cash supply. While in general the cash supply continues to grow, this may change as more and more commerce becomes digital. Sweden has already reached peak cash and is now seeing their total cash supply decline (without a corresponding decrease in money supply). ↩ -

That would be to say, that money decreases at or near the peak of a business cycles because of some delayed effect from the previous business cycle, rather than as an independent variable that will affect the current business cycle. ↩

-

Furthermore, it seems that depressions can be transmitted among countries with a common currency source (e.g. the gold standard, the current international dollar based payment regime), but are less likely transmitted outside of their home regime. China, for example, did not see a contraction during the first part of the Great Depression (it used silver as its monetary base, rather than gold) and only saw a contraction once the US began buying up silver, effectively shrinking the Chinese monetary supply. ↩

-

Although crucially, they don’t allow instant withdrawals, because they require some time to sell assets. ↩

-

We aren’t losing anything by making this distinction. The growth of products like credit cards has not affected the monetary transmission mechanism, see Has the Growth of Money Substitutes Hindered Monetary Policy? By Anna J Schwartz and Philip Cagan, 1975. ↩

-

Financial terms referring to banks are often oddly inverted. Customer deposits with banks are termed liabilities (as the bank is liable to return them), while loans the bank has made are assets (as someone else will hopefully pay the bank back for them). If you want to see which of your friends have been reading about economics, say “I think a lot of the loans that bank made have become liabilities”. The ones who visibly twitch or look confused are the ones studying economics. ↩

-

In addition to regulation, government policy can affect the deposit-reserve ratio. In the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve began, for the first time, to pay interest on reserves (both required reserves and excess reserves). This move led to a huge increase in excess reserves (to more than 16x required reserves by 2011; this happened because banks became very risk averse during the crisis and getting interest on their excess reserves became a risk-free way to make money) and a precipitous drop in the deposit-reserve ratio, which, as we discussed above, means a precipitous drop in the supply of money (which tends to lead to recessions and depressions). Scott Sumner calls this one of the greatest ever failures of monetary policy. ↩

-

In addition to cutting back on loans, this often results in banks selling assets, to try and increase the amount of cash they have on hand. If multiple banks run into trouble at once and they sell similar assets at the same time the value of the assets can drop precipitously, forcing other banks to sell and raising the possibility of multiple bank failures. This is called contagion, a word that came up a lot in the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. ↩

-

“Full employment” is a term economists use to mean “the unemployment rate during neutral macroeconomic conditions”, which is simply the unemployment rate outside of a recession or a speculative bubble. It’s my opinion that full employment is heavily dependent on the political and culture features of a country. Canada and America, for example, have rather different full employment rates (Canada’s allows more unemployment). I’d argue this is because Canada has more of a social safety net, which would imply that some people working in the US at “full employment” really would prefer not to work, but feel they have no other choice. This seems to fit well with empirical data. For example, when the extended unemployment benefits program ended in 2015, we simultaneously saw a drop in the unemployment rate and a decrease in wages. This is consistent with unemployed people suddenly scrambling for jobs at rather worse terms than they’d previously hoped for. ↩

-

Narrow exceptions apply and normally represent some sort of promotion or implicit sale. For example, short-term car loans on last year’s models will often be discounted below the target rate. It is generally a good idea to take a short-term loan at a below-target interest rate rather than pay a lump. This is not financial advice. ↩

-

Technically, for an event to qualify as a recession, there must be two quarters of successive contraction in national GDP. This never occurred during (or after) the Dot-com crash. Interestingly, the initial contraction was immediately preceded by the Federal Reserve signalling its intent to tighten monetary policy so as to rein in speculation, which it did by raising the interest rate target three times in quick succession. When markets crashed, it quickly reversed course, which may have played a role in averting a longer recession. ↩

-

This is another way of saying either “they try and return a deposit-reserve ratio that has become too high to normal” or “they try and shrink their deposit-reserve ratio”. In either case, the money supply is going to shrink. ↩

-

Banks, as Matt Levine likes to say are “a magical place that transforms risky illiquid long-term loans into safe immediately accessible deposits.” He goes on to point out that “like most magic, this requires a certain suspension of disbelief”. This is pretty socially useful; we want people to trust their bank accounts, but we also want loans for things like houses and factories and college to exist. Most of the time the magic works and everything is fine. But if people stop believing in the magic, it turns out that the guy behind the curtain is a bunch of loans that you can’t call due right away. If you try to, the bank fails. ↩

-

Remember, this is generally a good thing as it makes bank services much more affordable. If banks held onto all their reserves, banking services would be very expensive and many more disadvantaged people would be unbanked. ↩

-

Before insurance, only the first people to get to the bank would get their money back. This meant that you had a strong incentive to pull your money out at the very first sign of trouble. Otherwise stable and well-run banks could be undone by a rumour, as everyone panicked and flocked to the withdrawal counter. Deposit insurance changes the game; now no one has to rush to be first, which means no one needs to withdraw at all. ↩

-

Runaway inflation is bad! But a decrease in the money supply, or a decrease in the growth rate of the money supply is bad as well. A very irresponsible program of monetary growth could trigger double digit inflation. Failure to respond promptly to a decrease in the growth rate of money will cause a recession. Unfortunately, central banks aren’t blamed for recessions (by the government or the general populace) but are blamed for inflation, so they tend to act to minimize their chance of being blamed, instead of acting to maximize social good. ↩

-

Now in real life (as opposed to this simplified model), people probably don’t immediately spend or invest absolutely every extra dollar they get. They may expect to spend some extra in the near future and want to hold it in cash, or they may want to build up more than of a cushion.

This would be an example of an inelastic relationship, where a change in one variable (money supply) leads to a less than proportional change in another (spending/investment).

Still, the more money that is dumped into the economy, the closer we get to the idealized model. If you win $100 in a lottery, you may just leave it in your bank account. But if you win $1,000,000 you’re going to be spending some of it and investing a lot of the rest. ↩ -

Remember, it is possible for the central bank to increase interest rates (create less money) without changing the monetary growth rate. If banks are creating a lot of money and the economy is already at capacity, the central bank can sometimes safely cut back on the amount of money it’s creating while still allowing adequate money to be created by banks. This is why central banks often raise interest rates during booms. It can be necessary to keep inflation from rising. ↩

-

I am not the first to wonder if co-ops might be more “recession-proof” than conventional firms. Since co-ops generally operate via profit-sharing, rather than set wages, they may exhibit less downwards nominal wage rigidity (the economic term for people’s aversion to pay cuts), which means they might weather recessions with wage cuts, rather than outright job losses. I haven’t been able to find any studies on this subject, but I’d be very interested to see if they exist. ↩

-

There is a strain of leftist thought that views Paul Volcker reining in inflation as much worse for workers than any policy of Reagan’s. I’m trying to find a better explanation of this position somewhere and plan to write about it once I do. ↩