Last week I said that I’d been avoiding writing about Brexit because it was neither my monkeys nor my circus. This week, I’ll be eating those words.

I’m a noted enthusiast of the Westminster system of government, yet this week (with Teresa May’s deal failing in parliament and parliament taking control of Brexit proceedings, to uncertain ends) seems to fly in the face of everything good I’ve said about it. That impression is false; the current impasse has been caused entirely by recent ill-conceived British tinkering, not any core problems with the system itself.

As far as I can tell, the current shambles arise from three departures from the core of the Westminster system.

First, we have parliament taking control of the business of parliament in order to hold a set of indicative votes. I don’t have the sort of deep knowledge of British history that is necessary to assess whether this is unprecedented or not, but it is certainly unusual.

The majority in the house that controls the business of the house is, kind of definitionally, the government in a Westminster system. Unlike the American Republican system of government, the Brits don’t really have a notion of “the government” that extends beyond whomever can command the confidence of parliament. To have parliament in some sense (although not the formal one) withdraw that confidence, without forcing a new government to be appointed by the Queen or fresh elections is deeply unusual.

The whole point of the Westminster system is to always have a governing majority for key votes. If that breaks down, then either a new governing majority should arise, or new elections. Otherwise, you can have American-style gridlock.

This odd situation has arisen partially from the Fixed-term Parliaments Act of 2011, which severely limited the circumstances under which a sitting government can fall. Previously, all important legislation doubled as motions of confidence; defeat of any bill as strongly championed by the government as Teresa May’s Brexit bill would have resulted in new elections. Now, a motion of no-confidence (which requires a majority to amend a bill to add it, or for the government to schedule a motion of no confidence in itself) must pass, or 2/3 of the house must vote for an early election. This bar is considerably higher (as no government wants to go to the polls as a result of a no confidence motion), so it is much easier for a government to limp along, even when it lacks a working majority in the House of Commons.

It’s currently not clear what does have a working majority in parliament, although I suppose today’s indicative votes (where MPs will vote on a variety of Brexit proposals) will give us an idea.

Unfortunately, even if there’s a clear outcome from the indicative votes (and there’s no guarantee of that), there’s not a mechanism for enacting that. Either parliament will have to keep passing amendments every single day to take control of business from the government (which is supposed to be the entity setting business!), or the government has to buy into the outcome. If neither of those happen, the indicative votes will do nothing but encourage intransigence of those who know they have the support of many other MPs. If the rebels went to the Queen and asked to appoint a new government, this would obviously not be an issue, but MPs seem uninterested in taking that (arguably proper) step.

This all stems from the second problem, namely, that parliament is rubbish when constrained by external forces.

The way that parliament normally works is: people come up with a platform and try and get elected on it. If a majority comes from this process, then they implement the platform. They all signed off on it, after all. If there’s no clear majority, then people come up with a coalition agreement, which combines the platforms of multiple parties into some unholy mess that they can all agree to pass. In either case, the government agenda is clear.

The problem here is that there are people in each party on either side of the Brexit referendum. Some of them feel bound by the referendum results and some don’t, but even though its results were incorporated into party platforms, it still feels like a live issue to many MPs in a way that most issues in their platform just don’t.

It’s not even clear that there’s a majority of people in parliament in favour of Brexit. And when you have a government that feels bound by a promise to enact Brexit, but a parliament without a clear majority for any particular deal (or even a majority in favour of Brexit) you’re in for a bad time.

Basically “enact this referendum” and “keep 50% of the house happy” are two different goals and it is very easy to find them mutually incompatible. At this point, it becomes incredibly difficult to govern!

The third problem is Teresa May’s unwillingness to find another deal for the house. I get that there might not be any willingness in Europe to negotiate another deal and that she’s bound by a lot of domestic constraints, but there’s a longstanding tradition that MPs can’t vote on the same bill twice in one parliament. Australia is a rare Westminster system government that allows it, but only for bills that the senate rejects and with the caveat that a second rejection can be used to trigger an election.

This tradition exists so that the government can’t deadlock itself trying to get contentious legislation though. By ignoring it, Teresa May is showing contempt for parliament.

If, instead of standing by her bill after it had failed, she sought out some other bill that could get through parliament, she’d obviate the need for parliament to take matters into its own hands. Alternatively, if the Brexit vote had just been a confidence vote in the first place, she’d be able to ask the question of a brand-new parliament, which, if she headed it, presumably would have a popular mandate for her bill.

(And obviously if she didn’t head parliament, we wouldn’t have this particular impasse.)

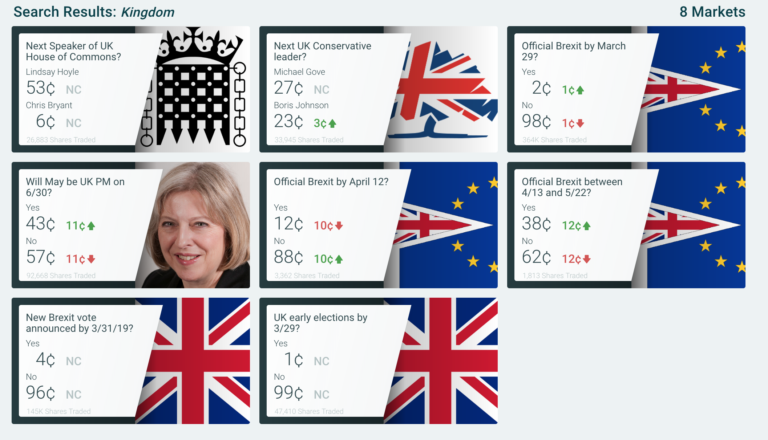

By ignoring and changing so many parliamentary conventions, the UK has stripped itself of its protections from deadlock, dooming us all to this seemingly endless Brexit Purgatory. At the time of writing, the prediction market PredictIt had the odds of Brexit at less than 2% by Friday and only 50/50 by May 22. May’s own chances are even worse, with only 43% of PredictIt users confident she would still be PM by the start of July.

I hope that parliament comes to its senses and that this is the last thing I’ll feel compelled to write about Brexit. Unfortunately, I doubt that will be the case.