A while back, I was linked to this Tweet:

| ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄|

— Audra J. Wolfe, PhD (@ColdWarScience) July 12, 2018

Science

has always

been

Political

|___________|

(\__/) ||

(•ㅅ•) ||

/ づ#HistorianSignBunny

It had sparked a brisk and mostly unproductive debate. If you want to see people talking past each other, snide comments, and applause lights, check out the thread. One of the few productive exchanges centres on bridges.

Bridges are clearly a product of science (and its offspring, engineering) – only the simplest bridges can be built without scientific knowledge. Bridges also clearly have a political dimension. Not only are bridges normally the product of politics, they also are embedded in a broader political fabric. They change how a space can be used and change geography. They make certain actions – like commuting – easier and can drive urban changes like suburb growth and gentrification. Maintenance of bridges uses resources (time, money, skilled labour) that cannot be then used elsewhere. These are all clearly political concerns and they all clearly intersect deeply with existing power dynamics.

Even if no other part of science was political (and I don’t think that could be defensible; there are many other branches of science that lead to things like bridges existing), bridges prove that science certainly can be political. I can’t deny this. I don’t want to deny this.

I also cannot deny that I’m deeply skeptical of the motives of anyone who trumpets a political view of science.

You see, science has unfortunate political implications for many movements. To give just one example, greenhouse gasses are causing global warming. Many conservative politicians have a vested interest in ignoring this or muddying the water, such that the scientific consensus “greenhouse gasses are increasing global temperatures” is conflated with the political position “we should burn less fossil fuel”. This allows a dismissal of the political position (“a carbon tax makes driving more expensive; it’s just a war on cars”) serve also (via motivated cognition) to dismiss the scientific position.

(Would that carbon in the atmosphere could be dismissed so easily.)

While Dr. Wolfe is no climate change denier, it is hard to square her claims that calling science political is a neutral statement:

You are getting warmer. Fascinating how “science” is read as “empirical findings” and “political” as inherently bad.

— Audra J. Wolfe, PhD (@ColdWarScience) July 12, 2018

With the examples she chooses to demonstrate this:

When chemists choose to produce synthetics at an industrial scale without investigating their safety, that’s a political choice.

— Audra J. Wolfe, PhD (@ColdWarScience) July 12, 2018

When pointing out that science is political, we could also say things like “we chose to target polio for a major elimination effort before cancer, partially because it largely affected poor children instead of rich adults (as rich kids escaped polio in their summer homes)”. Talking about the ways that science has been a tool for protecting the most vulnerable paints a very different picture of what its political nature is about.

(I don’t think an argument over which view is more correct is ever likely to be particularly productive, but I do want to leave you with a few examples for my position.)

Dr. Wolfe’s is able to claim that politics is neutral despite only using negative examples of its effects by using a bait and switch between two definitions of “politics”. The bait is a technical and neutral definition, something along the lines of: “related to how we arrange and govern our society”. The switch is a more common definition, like: “engaging in and related to partisan politics”.

I start to feel that someone is being at least a bit disingenuous when they only furnish negative examples, examples that relate to this second meaning of the word political, then ask why their critics view politics as “inherently bad” (referring here to the first definition).

This sort of bait and switch pops up enough in post-modernist “all knowledge is human and constructed by existing hierarchies” places that someone got annoyed enough to coin a name for it: the motte and bailey fallacy.

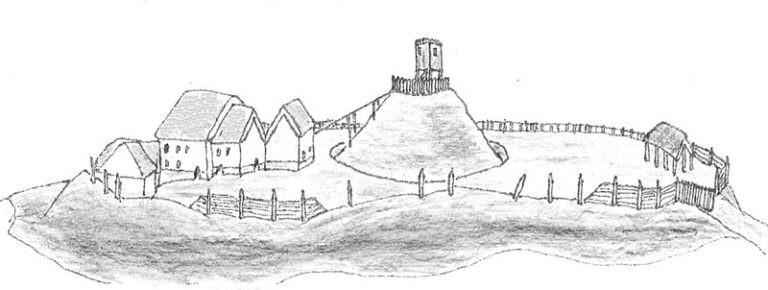

It’s named after the early-medieval form of castle, pictured above. The motte is the outer wall and the bailey is the inner bit. This mirrors the two parts of the motte and bailey fallacy. The “motte” is the easily defensible statement (science is political because all human group activities are political) and the bailey is the more controversial belief actually held by the speaker (something like “we can’t trust science because of the number of men in it” or “we can’t trust science because it’s dominated by liberals”).

From Dr. Wolfe’s other tweets, we can see the bailey (sample: “There’s a direct line between scientism and maintaining existing power structures; you can see it in language on data transparency, the recent hoax, and more.”). This isn’t a neutral political position! It is one that a number of people disagree with. Certainly Sokal, the hoax paper writer who inspired the most recent hoaxes is an old leftist who would very much like to empower labour at the expense of capitalists.

I have a lot of sympathy for the people in the twitter thread who jumped to defend positions that looked ridiculous from the perspective of “science is subject to the same forces as any other collective human endeavour” when they believed they were arguing with “science is a tool of right-wing interests”. There are a great many progressive scientists who might agree with Dr. Wolfe on many issues, but strongly disagree with what her position seems to be here. There are many of us who believe that science, if not necessary for a progressive mission, is necessary for the related humanistic mission of freeing humanity from drudgery, hunger, and disease.

It is true that we shouldn’t uncritically believe science. But the work of being a critical observer of science should not be about running an inquisition into scientists’ political beliefs. That’s how we get climate change deniers doxxing climate scientists. Critical observation of science is the much more boring work of checking theories for genuine scientific mistakes, looking for P-hacking, and doubled checking that no one got so invested in their exciting results that they fudged their analyses to support them. Critical belief often hinges on weird mathematical identities, not political views.

But there are real and present dangers to uncritically not believing science whenever it conflicts with your politic views. The increased incidence of measles outbreaks in vaccination refusing populations is one such risk. Catastrophic and irreversible climate change is another.

When anyone says science is political and then goes on to emphasize all of the negatives of this statement, they’re giving people permission to believe their political views (like “gas should be cheap” or “vaccines are unnatural”) over the hard truths of science. And that has real consequences.

Saying that “science is political” is also political. And it’s one of those political things that is more likely than not to be driven by partisan politics. No one trumpets this unless they feel one of their political positions is endangered by empirical evidence. When talking with someone making this claim, it’s always good to keep sight of that.