One of the best things about taking physics classes is that the equations you learn are directly applicable to the real world. Every so often, while reading a book or watching a movie, I’m seized by the sudden urge to check it for plausibility. A few scratches on a piece of paper later and I will generally know one way or the other.

One of the most amusing things I’ve found doing this is that the people who come up with the statistics for Pokémon definitely don’t have any sort of education in physics.

Takes Onix. Onix is a rock/ground Pokémon renowned for its large size and sturdiness. Its physical statistics reflect this. It’s 8.8 metres (28’) long and 210kg (463lbs).

Surely such a large and tough Pokémon should be very, very dense, right? Density is such an important tactile cue for us. Don’t believe me? Pick up a large piece of solid medal. Its surprising weight will make you take it seriously.

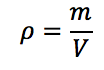

Let’s check if Onix would be taken seriously, shall we? Density is equal to mass divided by volume. We use the symbol ρ to represent density, which gives us the following equation:

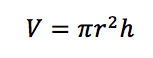

We already know Onix’s mass. Now we just need to calculate its volume. Luckily Onix is pretty cylindrical, so we can approximate it with a cylinder. The equation for the volume of a cylinder is pretty simple:

Where π is the ratio between the diameter of a circle and its circumference (approximately 3.1415…, no matter what Indiana says), r is the radius of a circle (always one half the diameter), and h is the height of the cylinder.

Given that we know Onix’s height, we just need its diameter. Luckily the Pokémon TV show gives us a sense of scale.

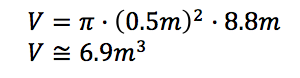

Judging by the image, Onix probably has an average diameter somewhere around a metre (3 feet for the Americans). This means Onix has a radius of 0.5 metres and a height of 8.8 metres. When we put these into our equation, we get:

For a volume of approximately 6.9m3. To get a comparison I turned to Wolfram Alpha which told me that this is about 40% of the volume of a gray whale or a freight container (which incidentally implies that gray whales are about the size of standard freight containers).

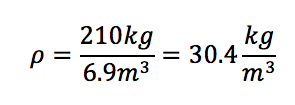

Armed with a volume, we can calculate a density.

Okay, so we know that Onix is 30.4 kg/m3, but what does that mean?

Well it’s currently hard to compare. I’m much more used to seeing densities of sturdy materials expressed in tonnes per cubic metre or grams per cubic centimetre than I am seeing them expressed in kilograms per cubic metre. Luckily, it’s easy to convert between these.

There are 1000 kilograms in a ton. If we divide our density by a thousand we can calculate a new density for Onix of 0.0304t/m3.

How does this fit in with common materials, like wood, Styrofoam, water, stone, and metal?

| Material | Density |

|---|---|

| Styrofoam | 0.028 |

| Onix | 0.03 |

| Balsa | 0.16 |

| Oak1 | 0.65 |

| Water | 1 |

| Granite | 2.6 |

| Steel | 7.9 |

From this chart, you can see that Onix’s density is eerily close to Styrofoam. Even the notoriously light balsa wood is five times denser than him. Actual rock is about 85 times denser. If Onix was made of granite, it would weigh 18 tonnes, much heavier than even Snorlax (the heaviest of the original Pokémon at 460kg).

While most people wouldn’t be able to pick Onix up (it may not be dense, but it is big), it wouldn’t be impossible to drag it. Picking up part of it would feel disconcertingly light, like picking up an aluminum ladder or carbon fibre bike, only more so.

How did the creators of Pokémon accidently bestow one of the most famous of their creations with a hilariously unrealistic density?

I have a pet theory.

I went to school for nanotechnology engineering. One of the most important things we looked into was how equations scaled with size.

Humans are really good at intuiting linear scaling. When something scales linearly, every twofold change in one quantity brings about a twofold change in another. Time and speed scale linearly (albeit inversely). Double your speed and the trip takes half the time. This is so simple that it rarely requires explanation.

Unfortunately for our intuitions, many physical quantities don’t scale linearly. These were the cases that were important for me and my classmates to learn, because until we internalized them, our intuitions were useless on the nanoscale. Many forces, for example, scale such that they become incredibly strong incredibly quickly at small distances. This leads to nanoscale systems exhibiting a stickiness that is hard on our intuitions.

It isn’t just forces that have weird scaling though. Geometry often trips people up too.

In geometry, perimeter is the only quantity I can think of that scales linearly with size. Double the length of the sides of a square and the perimeter doubles. The area, however does not. Area is quadratically related to side length. Double the length of a square and you’ll find the area quadruples. Triple the length and the area increases nine times. Area varies with the square of the length, a property that isn’t just true of squares. The area of a circle is just as tied to the square of its radius as a square is to the square of its length.

Volume is even trickier than radius. It scales with the third power of the size. Double the size of a cube and its volume increases eight-fold. Triple it, and you’ll see 27 times the volume. Volume increases with the cube (which again works for shapes other than cubes) of the length.

If you look at the weights of Pokémon, you’ll see that the ones that are the size of humans have fairly realistic weights. Sandslash is the size of a child (it stands 1m/3’ high) and weighs a fairly reasonable 29.5kg.

(This only works for Pokémon really close to human size. I’d hoped that Snorlax would be about as dense as marshmallows so I could do a fun comparison, but it turns out that marshmallows are four times as dense as Snorlax – despite marshmallows only having a density of ~0.5t/m3)

Beyond these touchstones, you’ll see that the designers of Pokémon increased their weight linearly with size. Onix is a bit more than eight times as long as Sandslash and weighs seven times as much.

Unfortunately for realism, weight is just density times volume and as I just said, volume increases with the cube of length. Onix shouldn’t weigh seven or even eight times as much as Sandslash. At a minimum, its weight should be eight times eight times eight multiples of Sandslash’s; a full 512 times more.

Scaling properties determine how much of the world is arrayed. We see extremely large animals more often in the ocean than in the land because the strength of bones scales with the square of size, while weight scales with the cube. Become too big and you can’t walk without breaking your bones. Become small and people animate kids’ movies about how strong you are. All of this stems from scaling.

These equations aren’t just important to physicists. They’re important to any science fiction or fantasy writer who wants to tell a realistic story.

Or, at least, to anyone who doesn’t want their work picked apart by physicists.

-

Not the professor. His density is 0.985t/m3. ↩