When you’re noticing that you’re talking past someone, what does it look like? Do you feel like they’re ignoring all the implications of the topic at hand (“yes, I know the invasion of Iraq is causing a lot of pain, but I think the important question is, ‘did they have WMDs?’”)? Or do you feel like they’re avoiding talking about the object-level point in favour of other considerations (“factory farmed animals might suffer, but before we can consider whether that’s justified or not, shouldn’t we decide whether we have any obligation to maximize the number of living creatures?”)?

I’m beginning to suspect that many tense disagreements and confused, fruitless conversations are caused by differences in how people conceive of and process the truth. More, I think I have a model that explains why some people can productively disagree with anyone and everyone, while others get frustrated very easily with even their closest friends.

The basics of this model come from a piece that Jacob Falkovich wrote for Quillette. He uses two categories, “contextualizers” and “decouplers”, to analyze an incredibly unproductive debate (about race and IQ) between Vox’s Ezra Klein and Dr. Sam Harris.

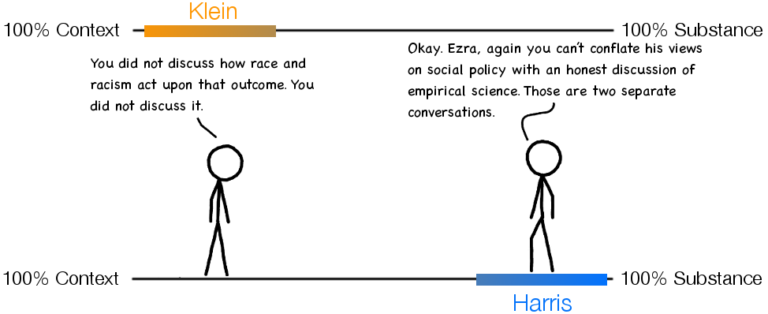

Klein is the contextualizer, a worldview that comes naturally to a political journalist. Contextualizers see ideas as embedded in a context. Questions of “who does this effect?”, “how is this rooted in society?”, and “what are the (group) identities of people pushing this idea?” are the bread and butter of contextualizers. One of the first things Klein says in his debate with Harris is:

Here is my view: I think you have a deep empathy for Charles Murray’s side of this conversation, because you see yourself in it [because you also feel attacked by "politically correct" criticism]. I don’t think you have as deep an empathy for the other side of this conversation. For the people being told once again that they are genetically and environmentally and at any rate immutably less intelligent and that our social policy should reflect that. I think part of the absence of that empathy is it doesn’t threaten you. I don’t think you see a threat to you in that, in the way you see a threat to you in what’s happened to Murray. In some cases, I’m not even quite sure you heard what Murray was saying on social policy either in The Bell Curve and a lot of his later work, or on the podcast. I think that led to a blind spot, and this is worth discussing.

Klein is highlighting what he thinks is the context that probably informs Harris’s views. He’s suggesting that Harris believes Charles Murray’s points about race and IQ because they have a common enemy. He’s aware of the human tendency to like ideas that come from people we feel close to (myside bias) – or that put a stick in the eye of people we don’t like.

There are other characteristics of contextualizers. They often think thought experiments are pointless, given that they try and strip away all the complex ways that society affects our morality and our circumstances. When they make mistakes, it is often because they fall victim to the “ought-is” fallacy; they assume that truths with bad outcomes are not truths at all.

Harris, on the other hand, is a decoupler. Decoupling involves separating ideas from context, from personal experience, from consequences, from anything but questions of truth or falsehood and using this skill to consider them in the abstract. Decoupling is necessary for science because it’s impossible to accurately check a theory when you hope it to be true. Harris’s response to Klein’s opening salvo is:

I think your argument is, even where it pretends to be factual, or wherever you think it is factual, it is highly biased by political considerations. These are political considerations that I share. The fact that you think I don’t have empathy for people who suffer just the starkest inequalities of wealth and politics and luck is just, it’s telling and it’s untrue. I think it’s even untrue of Murray. The fact that you’re conflating the social policies he endorses — like the fact that he’s against affirmative action and he’s for universal basic income, I know you don’t happen agree with those policies, you think that would be disastrous — there’s a good-faith argument to be had on both sides of that conversation. That conversation is quite distinct from the science and even that conversation about social policy can be had without any allegation that a person is racist, or that a person lacks empathy for people who are at the bottom of society. That’s one distinction I want to make.

Harris is pointing out that questions of whether his beliefs will have good or bad consequences or who they’ll hurt have nothing to do with the question of if they are true. He might care deeply about the answers of those questions, but he believes that it’s a dangerous mistake to let that guide how you evaluate an idea. Scientists who fail to do that tend to get caught up in the replication crisis.

When decouplers err, it is often because of the is-ought fallacy. They fail to consider how empirical truths can have real world consequences and fail to consider how labels that might be true in the aggregate can hurt individuals.

When you’re arguing with someone who doesn’t contextualize as much as you do, it can feel like arguing about useless hypotheticals. I once had someone start a point about police shootings and gun violence with “well, ignoring all of society…”. This prompted immediate groans.

When arguing with someone who doesn’t decouple as much as you do, it can feel useless and mushy. A co-worker once said to me “we shouldn’t even try and know the truth there – because it might lead people to act badly”. I bit my tongue, but internally I wondered how, absent the truth, we can ground disagreements in anything other than naked power.

Throughout the debate between Harris and Klein, both of them get frustrated at the other for failing to think like they do – which is why it provided such a clear example for Falkovich. If you read the transcripts, you’ll see a clear pattern: Klein ignores questions of truth or falsehood and Harris ignores questions of right and wrong. Neither one is willing to give an inch here, so there’s no real engagement between them.

This doesn’t have to be the case whenever people who prefer context or prefer to deal with the direct substance of an issue interact.

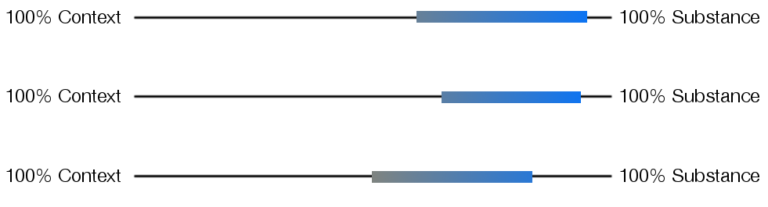

My theory is that everyone has a window that stretches from the minimum amount of context they like in conversations to the minimum amount of substance. Theoretically, this window could stretch from 100% context and no substance to 100% substance and no context.

![]()

But practically no one has tastes that broad. Most people accept a narrower range of arguments. Here’s what three well compatible friends might look like:

We should expect to see some correlation between the minimum and maximum amount of context people want to get. Windows may vary in size, but in general, feeling put-off by lots of decoupling should correlate with enjoying context.

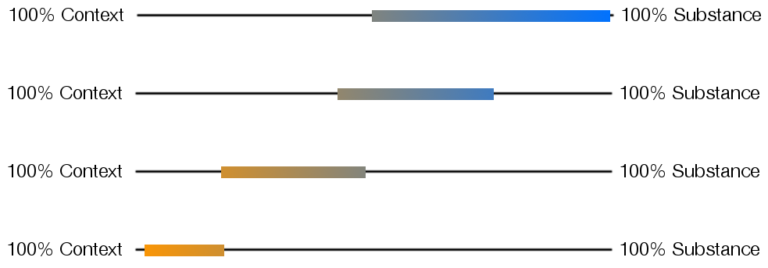

Klein and Harris disagreed so unproductively not just because they give first billing to different things, but because their world views are different enough that there is absolutely no overlap between how they think and talk about things.

I’ve found thinking about windows of context and substance, rather than just the dichotomous categories, very useful for analyzing how me and my friends tend to agree and disagree.

Some people I know can hold very controversial views without ever being disagreeable. They are good at picking up on which sorts of arguments will work with their interlocutors and sticking to those. These people are no doubt aided by rather wide context windows. They can productively think and argue with varying amounts of context and substance.

Other people feel incredibly difficult to argue with. These are the people who are very picky about what arguments they’ll entertain. If I sort someone into this internal category, it’s because I’ve found that one day they’ll dismiss what I say as too nitty-gritty, while the next day they criticize me for not being focused enough on the issue at hand.

What I’ve started to realize is that people I find particularly finicky to argue with may just have a fairly narrow strike zone. For them, it’s simultaneously easy for arguments to feel devoid of substance or devoid of context.

I think one way that you can make arguments with friends more productive is explicitly lay out the window in which you like to be convinced. Sentences like: “I understand what you just said might convince many people, but I find arguments about the effects of beliefs intensely unsatisfying” or “I understand that you’re focused on what studies say, but I think it’s important to talk about the process of knowledge creation and I’m very unlikely to believe something without first analyzing what power hierarchies created it” are the guideposts by which you can show people your context window.