There are many problems that face modern, developed economies. Unfortunately, no one agrees with what to do in response to them. Even economists are split, with libertarians championing deregulation, while liberals call for increased government spending to reduce inequality.

Or at least, that’s the conventional wisdom. The Captured Economy, by Dr. Brink Lindsey (libertarian) and Dr. Steven M. Teles (liberal) doesn’t have much time for conventional wisdom.

It’s a book about the perils of regulation, sure. But it’s a book that criticizes regulation that redistributes money upwards. This isn’t the sort of regulation that big pharma or big finance wants to cut. It’s the regulation they pay politicians to enact.

And if you believe Lindsey and Teles, upwardly redistributing regulation is strangling our economy and feeding inequality.

They’re talking, of course, about rent-seeking.

Now, if you don’t read economic literature, you probably have an idea of what “rent-seeking” might mean. This idea is probably wrong. We aren’t talking here about the sorts of rents that you pay to landlords. That rent probably includes some economic rents (quite a lot of economic rents if you live in Toronto, Vancouver, San Francisco, or New York), but does not itself represent an economic rent.

An economic rent is any excess payment due to scarcity. If you control especially good land and can grow wheat at half the price of everyone else, the rent of this land is the difference between how much it costs you to grow wheat and how much it costs everyone else to grow wheat.

Rent-seeking is when someone tries to acquire these rents without producing anything of value. It isn’t rent-seeking when you invent a new mechanical device that cuts your costs in half (although your additional profit will represent economic rents). It is rent-seeking when you use some of those profits as “campaign contributions” to get the government to pass a law that requires all future labour-saving devices need to be “tested” for five years before they can be introduced. Over that five-year period, you’ll reap rents because no one else can compete with you to bring the price of the goods you are producing down.

How could we know if rent-seeking is happening in the US economy (note: this book is written specifically about the US, so assume all statements here are about the US unless otherwise noted) and how can we tell what it’s costing?

Well, one of the best signs of rent-seeking is increased profits. If profits are increasing and this can’t be explained by innovation or productivity growth or any other natural factor, then we have circumstantial evidence that profits are increasing from rent-seeking. Is this the case?

Lindsey and Teles say yes.

First, it seems like profits for US firms are increasing, from a low of 3% in the 1980s to a high of 11% currently. These are average profits, so they can’t be swayed by one company suddenly becoming much more efficient – as something like that should be cancelled out by a decline in profits at somewhere less efficient.

At the same time, however, the majority of these new profits have been going to companies that were already very profitable. If being very profitable makes corrupting the political process easier, this is exactly what we’d expect to see.

In addition, formation of new companies has slowed, concentration has increased, the ratio of intangible assets to tangible assets has increased, and yet spending on intangible assets (like R&D) has dropped. The only intangibles you get without investing in R&D are better human capital (but then why should profits increase if this is happening everywhere?) and tailor-made regulation.

Lindsey and Teles go on to cite research by Dr. James Bessen that show that most of the increases in profits since the start of the 21st century is heavily correlated with increasing regulation, a result that remained robust even when accounting for reverse causation (e.g. a counter-factual where profits causing regulation).

This circumstantial evidence is about all we can get for something as messy as real-world economics, but it’s both highly suggestive and fits in well with what keen observers have noted in individual industries, like the pharmaceutical industry.

An increase in rent-seeking would explain a whole bunch of the malaise of the current economy.

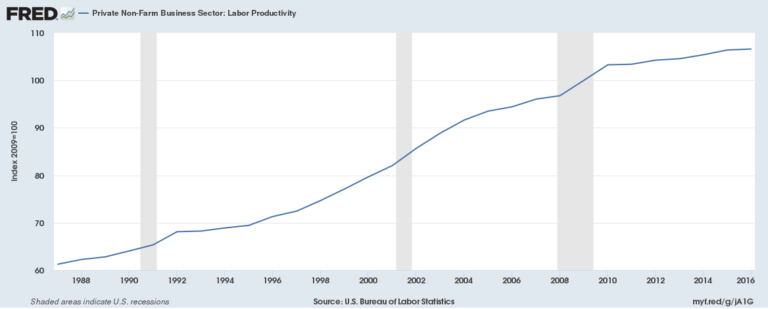

Economists have been surprised by the slow productivity growth since the last recession. If there was significantly more rent-seeking now than in the past, then we would expect productivity growth to slow.

In a properly functioning economy, productivity growth is largely buoyed up by new entrants to a field. The most productive new entrants thrive, while less productive new entrants (and some of the least productive existing players) fail. Over time, this gradually improves the overall productivity of an industry. This is the creative destruction you might hear economists talking glowingly about.

Productivity can also be raised by the slow diffusion of innovations across an industry. When best practices are copied, everyone ends up producing more with fewer inputs.

Rent-seeking changes the nature of this competition. Instead of competing on productivity and innovation, companies compete to see who can most effectively buy the government. Everyone who fails to buy off the government will eventually fail, leaving an increasingly moribund economy behind.

Lindsey and Teles believe that we’re more likely to see the negative effects of rent-seeking today than in the past because the underlying economy has less favourable conditions. In the 1950s, women started to enter the workforce. In the 60s, Boomers began to enter it. In addition, many returning soldiers got university educations after World War II, making college graduates much more common.

All of these trends have now stagnated or reversed. It’s hard for developed countries to get any more educated. Most of the women who want to or have to work are already in the labour force. And the Boomers are starting to retire. Therefore, we can no longer rely on strong underlying growth. We either need a lot of investment or a lot of productivity growth if we’re going to see strong overall growth. And it’s politically hard to get people to delay their consumption to invest.

Therefore, rent-seeking, as a force holding down productivity growth, would be a serious problem in political economy even if it didn’t lead to increased inequality and all of the problems that can cause.

But that’s where the other half of this book comes in; the authors suggest that our current spate of rent-seeking policies are fueling income inequality as well as economic malaise1. Rent-seeking inflates stock prices (which only helps people who are well-off enough that they own stocks) or wages at the top of corporations. Rents from rent-seeking also tend to accrue to skilled workers, to people who own homes, and people in regulated professions. All of these people are wealthier than average and increasing their wealth increases inequality.

That’s the theory. To show it in practice, Lindsey and Teles introduce four case studies: finance, intellectual property, zoning, and occupational licensing.

Finance

Whenever I think about finance, I am presented with a curious double image. There are the old-timey banks of yore, that I see in movies, the ones that provided smiling service to their local customers. And then there are the large financial entities that exist today, with their predatory sales tactics and “too big to fail” designations. Long gone are the days when banks mostly made money by collecting interest on loans, loans made possible by paying interest on deposits.

Today’s banks also have an excellent racket going on. They decry taxes and regulation on one hand, while extracting huge rents from governments on the other.

To understand why, we first need to talk about leverage. Bank profits can be increased many times over via the magic of leverage – basically borrowing money to buy assets. If you believe, for example, that the price of silver is going to skyrocket tomorrow, you could buy $100 of silver. If silver goes up by 20%, you’ll pocket a cool $20 for 20% profit. If you borrow an extra $900 from friends and family at 1% interest and buy silver with that too, you’ll pocket a cool $191 once it goes up (20% of $1000 less 1% of $900), for 191% profit.

Leverage becomes a problem when prices fall. If the price goes down by 10% instead of going up, you’ll be left with $90 if you didn’t leverage yourself – and $1 if you did. Because it leads to the potential of outsized losses, leverage presents problems with downside risks, the things that happen when your bet is wrong.

One of the major ways banks extract rents is by forcing the government to hold onto their downside risks. In America, this is accomplished several ways. First, deposits are insured by the government. This is good, in that it prevents bank runs2, which were a significant problem in the 19th and 20th century, but bad because it removes most incentive for consumers to care about the lending practices of their bank. Insurance removes the risk associated with picking a bank with risky lending practices, so largely people don’t bother to see if their bank is responsible or not. Banks know this, so feel no pressure to be responsible, especially because shareholders love the profits irresponsibility brings in good times.

Second, the government (especially in America, but also recently in Ireland) seems unable to resist insulating bondholders from the consequences of backing a bank with bad standards. The bailouts after the financial crisis mean that few bondholders were punished for their failure to do due diligence when providing the credit banks used to make leveraged bets. As long as no one is punished for lending to the banks that make risky bets, things won’t get better.

(Interestingly, there is theoretical work that shows banks can accomplish everything they currently do with debt using equity at the same cost. This isn’t what we see in real life. Lindsey and Teles suggest this is because debt is kept artificially cheap for banks by repeated bailouts. Creditors don’t demand extra to lend to an indebted bank, because they know they won’t have to pay if things go south.)

Third, there’s mortgage debt, which is often insured or bought by the Federal Government in America. This makes risky lending much more palatable for many banks (and much more profitable as well). This whole process is really opaque and largely hidden from the US population. When times are good, it’s a relatively cheap way to make housing more affordable (although somewhat regressive; it favours the already wealthy). When times are bad it can cost the government almost $200 billion.

The authors suggest that this sort of “public program by kluge” is the perfect vehicle for rent-seeking. The need to do the program in a klugey way so that taxpayers don’t complain is anathema to accountability and often requires the support of businesses – which are happy to help as long as they get to skim off the top. Lindsey and Teles suggest that it would be much better for the US just to provide straight up housing subsidies in a means-tested way.

Being able to extract all these rents has probably increased the size of the US financial sector. Linsey and Teles argue that this is a very bad thing. They cite data that show decreased economic growth once the financial sector grows beyond a certain size, possibly because an outsized financial sector leads to misallocation of resources.

Beyond a certain point, the financial sector is just moving money around to no productive aim (this is different than e.g. loans to businesses; I’m talking about highly speculative bets on foreign currencies or credit default swaps here). The financial sector also aggressively recruits very bright people using very high salaries. If the financial sector were smaller and couldn’t compensate as highly, then these people would be out doing something productive, like building self-driving cars or curing malaria. Lindsey and Teles suggest that we should happily make a trade-off whereby these people can’t get quite as high salaries but do actually produce things of value.

(Remember: one of the pair here is a libertarian! Like “worked for Cato Institute for years” libertarian. If your caricature of libertarians is that “they hate poor people”, I suggest you consider the alternative: “they think the free market is the best way to help disadvantaged people find better circumstances”. Here, Lindsey is trying to correct market failures and misallocations caused by big banks getting too cozy with the government.)

Intellectual Property Law

If you don’t follow the Open Source or Creative Commons movements, you probably had mostly positive things to say about copyright until a few years ago when the protests against SOPA and PIPA – two bills designed to strengthen copyright enforcement – painted the internet black in opposition.

SOPA and PIPA weren’t some new overreach. They are a natural outgrowth of a US copyright regime that has changed radically from its inception. In the early days of the American Republic, copyrights required registering. Doing so would give you a fourteen-year term of exclusivity, with the option to extend it once for another fourteen years. Today all works, even unpublished ones, are automatically granted copyright for the life of the author… plus 70 years.

Penalties have increased as well; previously, copyright infringement was only a civil matter. Now it carries criminal penalties of up to $250,000 in fines and 1-5 years of jail time per infringement.

Patent protections have also become onerous, although here the fault is judicial action, not statute. Appeals for patent cases are solely handled by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. This court is made up of judges who are normally former patent lawyers and who attend all the same conferences as patent lawyers – and eat the food paid for by the sponsors. I don’t want to claim judicial corruption, but it is perhaps unsurprising that these judges have come to see the goals of patent holders as right and noble.

Certainly, they’ve broken with past tradition and greatly expanded the scope of patentability while reducing the requirements for new patents. Genes, business methods, and most odiously, software, have been made patentable. Consequently, patents filed have increased from approximately 60,000 yearly in 1983 to 300,000 per year by 2013. If this represented a genuine increase in invention, then it would be a cause for celebration. But we already know that R&D spending isn’t increasing. It would be very surprising – and the exact opposite of what diminishing returns would normally suggest – if companies managed to come up with an additional 240,000 patents per year with no additional real spending.

What if these patents just came from increased incentives for rent-seeking via the intellectual property system?

“Intellectual property” conjures a happy image. Who doesn’t like property3? Many (most?) people support paying authors, artists, and inventors for their creations, at least in the abstract4. Lindsey and Teles argue that we should instead take a dim view of intellectual property; to them, it’s almost entirely rent-seeking.

They point out that many of supposed benefits of intellectual property never manifest. It’s unclear if it spurs invention (evidence from World Fairs suggest that it just moves invention towards whatever types of inventions are patentable, where payoff is more certain). It’s unclear if it incentivizes artists and writers (although we’ve seen music revenue fall, more people than ever are producing music). My personal opinion is that copyright doesn’t encourage writers; most of us couldn’t stop if we wanted to.

When it comes to software patents, the benefits are even less clear and the harms even greater. OECD finds that software patents are associated with a decrease in R&D spending, while Vox reports that costs associated with software patent lawsuits have now reached almost $70 billion annually. The majority of software patent litigation isn’t even launched by the inventors. Instead, it’s done by so called “patent trolls”, who buy portfolios of patents and then threaten to sue any company who doesn’t settle with them over “infringement”.

When even a successfully-defended lawsuit can cost millions of dollars (not to mention several ulcers), software patents (often for obvious ideas and assuredly improper) held by trolls represent a grave threat to innovation.

All of this adds up to a serious drag on the economy, not to mention our culture. While “protecting property” is seen as a noble goal by many, Lindsey and Teles argue that IP protections go well beyond that. They acknowledge that it makes sense to protect a published work in its entirety. But protecting the setting? The characters? The right to make sequels? That’s surely too much. How is George Lucas hurt if someone can sell their Star Wars fanfiction? How is that “infringing” on what he has created?

They have less sympathy for patents, which grant a somewhat ridiculous monopoly. If you patent something three days before I independently invent it, then any use or sale by me is still considered infringement even though I am assuredly not ripping you off.

Lindsey and Teles suggest that IP laws need to be rolled back to a more reasonable state, when copyright was for 14 years and abstract ideas, software implementation, and business methods couldn’t be patented. About the only patents they really approve of are pharmaceutical patents, which they view as necessary to protect the large upfront costs of drug development (see also Scott Alexander’s argument for why this is the case 5); I’d like to add that these upfront costs would be lower if the rent-seeking by pharmaceutical companies hadn’t supported rent-seeking regulation that has made the FDA an almost impenetrable tar-pit.

Occupational Licensing

Occupational licensing has definitely become more common. It’s gone from affecting 10% of the workforce (1970) to 30% of the workforce today. It no longer just affects doctors, teachers, lawyers, and engineers. Now it covers make-up artists, auctioneers, athletic trainers, and barbers.

Now, there are sometimes good reasons to license professionals. No one wants to drive across a bridge built by someone who hasn’t learned anything about physics. But there’s good reason to suspect that much of the growth of occupational licensing isn’t about consumer protection, despite what proponents say.

First of all, there’s often a quite a bit of variability in how many days of study these newly licensed professions require. Engineering requirements tend to be similar from country to country because it’s governed by international treaty. On the other hand, manicurist requirements vary wildly by state; Alaska requires three days of education, while Alabama requires 163. There’s no national standards at all. If this was for consumer protection, then presumably some states are well below what’s required and others are well above it.

Second, there’s no allowance for equivalencies. Engineers can take their engineering degrees anywhere and can transfer professional status with limited hassles. Lawyers can take the bar exam wherever they want. But if you get licensed as a manicurist in Alabama, Alaska won’t respect the license. And vice versa.

(Non-transferability is a serious economic threat in its own right, because it makes people less likely to move in search of better conditions. The section on zoning further explains why this is bad.)

Several studies have shown that occupational licenses do nothing to improve services to customers. Randomly sampled floral arrangements from licensed and unlicensed states (yes, some states won’t let you arrange flowers without a license) are judged the same when viewed by unsuspecting judges. Roofing quality hasn’t fallen after hurricanes, when licensing restrictions are lifted (and if there’s ever a time you’d expect quality to fall, it’s then!).

Despite the lack of benefits, there are very real costs to occupational licensing. Occupational licensing is associated with consumers paying prices between 5% and 33% above unlicensed areas, which translates to an average 18% increase in wages for licensed professionals. The total yearly cost to consumers for this price gouging? North of $200 billion. Unfortunately, employment growth is also affected. Licensed professions see 20% slower employment growth compared to neighbouring unlicensed jurisdictions. Licensing helps some people make more money, but they make this money by, in essence, pulling up the ladder to prosperity behind them.

Occupational licensing especially hurts minorities in the United States. Many occupational licenses require a college degree (black and Latino Americans are less likely to have college degrees) and they often exclude anyone with a criminal record of any sort (disproportionately likely to be black or Latino). It may make sense to exclude people with criminal records from certain jobs. But from manicuring? I don’t see how someone could do worse damage manicuring then they could preparing fast food, and that isn’t regulated at all.

Licensing boards often protect their members against complaints from the public. Since the board is composed only of members of the profession, it’s common for them to close ranks around anyone accused of bad conduct. The only profession I’ve seen that doesn’t do this is engineers. Compare the responses of professional boards to medical and engineering malpractice in Canada.

Probably the most interesting case of rent-seeking Lindsey and Teles identify are lawyers in the United States. While they accuse lawyers of engaging in the traditional rent-seeking behaviour of limiting entry to their field (and point out that bar exam difficulty is proportional to the number of people seeking admittance, which suggests that its main purpose it to keep supply from rising), they also claim that lawyers in the United States artificially raise demands for their services.

Did you know that lawyers made up 41% of the 113th Congress, despite representing only 0.6% of the US population? I knew the US had a lot of lawyers in politics, but I hadn’t realized it was that high. Lindsey and Teles charge these lawyers with writing the kind of laws that make sense to lawyers: abstruse, full of minutia, and fond of adversarial proceedings. Even if this isn’t a sinister plot, it certainly is a nice perk6.

I do wish this chapter better separated what I think is dual messages on occupational licensing. One strand of arguments goes: “occupational licensing for jobs like barbers, manicurists, etc. is keeping disadvantaged people, especially minorities out of these fields with slightly better than average wages and making everyone pay a tiny bit more”. The other is: “professionals are robbing everyone else blind because of occupational licensing; lawyers and doctors make a huge premium in the United States and are disproportionately wealthy compared to other countries and make up a large chunk of the 1%”.

I’d like them separated because they seem to call for separate solutions. We might decide that if we could fix the equality issues (for example, by scrapping criminal records checks and college degree requirements where they aren’t needed), it might make sense to keep occupational licensing to prevent a race for the bottom among occupations that have never represented a significant fraction of individual spending. One thing I noticed is that the decline among union membership is exactly mirrored by the increase in occupational licensing. In a very real way, occupational licensing, with some tweaks, could be the new unions.

On the other hand, we have doctors and lawyers (and maybe even engineers, although my understanding is that they do far less to restrict supply, especially foreign supply) who are making huge salaries that (in the case of lawyers) might be up to 50% rents from artificially low supply. If we undid some of the artificial barriers to entry they’ve thrown up, we could lower their wages and improve income equality while at the same time improving competition and opening up these fields (which should still pay reasonably well) to more people. Many of us probably know people who’d make perfectly fine doctors that have been kept out of medical school by the overly restrictive quotas. Where’s the harm in having two doctors making $90,000/year instead of one doctor making $180,000/year? It’s not like we couldn’t find a use for twice as many doctors!

Zoning

The weirdest thing about the recent rise in housing prices is that building houses hasn’t really gotten any more expensive. Between 1950 and 1970, housing prices increased 35% above inflation (when normalized to size) and construction costs increased 28% above inflation. Between 1970 and 2000, construction prices rose 6% slower than inflation – becoming cheaper in real terms – and overall housing costs increased 72% above inflation.

Maybe house prices have gone up because house quality has improved? Not so say data from repeat house sales. When analyzing these data, economists have determined that increased house quality can account for at most 25% of the increase in prices.

Maybe land is just genuinely running out in major cities? Well, if that were the case, we’d see a strong relationship between density and price. After all, density would surely emerge if land were running out, right? When analyzing these data, economists have found no relationship between city density and average home price.

The final clue comes from comparing the value of land houses can be built on with the value of land houses cannot be built on. When you look at how much the size of a lot affects the sale price of very similar homes and compare that with the cost of the land that goes under a house (by subtracting construction costs from the sale prices of new homes), you’ll find that the land under a house is worth ten times the land that simply extends a yard.

This suggests that a major component of rising house prices is the cost of getting permission to build a house on land – basically, finding some of the limited supply of land zoned for actually building anything. This is not land value per se, but instead a rent imposed by onerous zoning requirements. In San Francisco, San Jose, and Manhattan, this zoning cost is responsible for approximately half of house worth.

The purpose of zoning has always been to protect the value of existing homes, by keeping “undesirable” land usage out of a neighbourhood. Traditionally, “undesirable” has been both racist and classist. No one in a well-off neighbourhood wanted any of “those people” to move there, lest prospective future buyers (who shared their racial and social prejudices) not want to move to the neighbourhood. Today, zoning is less explicitly racist (even if it still prices minorities out of many neighbourhoods) and more nakedly about preserving house value by preventing any increase in density. After all, if you live in a desirable neighbourhood, the last thing you want is a large tower bringing in hundreds of new residents at affordable prices. How will you be able to get a premium on your house then? The market will be saturated!

Now if there were no real benefits to living in a city, Lindsey and Teles probably wouldn’t care about zoning. But there definitely are very good reasons why we want more people to be able to live in cities. First: transportation. Transportation is easier when people are densely packed, which makes supplies cheaper and reduces negative externalities from carbon intensive travel. Second: choice. Cities have enough people to allow people to make profits off of weird things, to allow people to carefully choose their jobs, and to allow employers choice in employees. All of these are helpful to the economy. Third: ineffable increases in human capital. There’s just something about cities (theorized to be “information spillover” between people in unrelated jobs) that make them much more productive per capita than anywhere else.

This productivity is rewarded in the form of higher wages. Lindsey and Teles claim that the average income of a high school graduate in Boston is 40% higher than the average income of a college graduate in Flint, Michigan. I’ll buy these data, but I’m a bit skeptical that this results in any more take-home pay for the Bostonian, because wages in Boston have to be higher if people are to live there. Would this hold true if you looked at real wages accounting for differences in cost of living7?

If wages are genuinely higher in places like Boston in real terms, then this spatial inequality should be theoretically self-correcting. People from places like Flint should all move to places like Boston, and we’ll see a sudden drop in income inequality and a sudden jump in standard of living for people who only have high school degrees. Lindsey and Teles believe this isn’t happening because the scarcity of housing drives up the initial price of moving far beyond what people without substantial savings can pay – the same people who most need to be able to move8.

Remember, many apartments require first and last month’s rent, plus a security deposit. I looked up San Francisco on PadMapper and the median rent looks to be something like $3300, a number that agrees with a cursory Google. Paying first and last on that, plus a damage deposit would cost you over $7,000. Add to that moving expenses, and you can see how it could be impossible for someone without savings to move to San Francisco, even if they could expect a relatively well-paid job.

(Lack of movement hurts people who stay behind as well. When people move away in search of higher wages, businesses must eventually raise wages in places seeing a net drain of people, lest the whole workforce disappear. This effect probably led to some of the convergence in average income between states that occurred from 1880 to 1980, an effect that has now markedly slowed.)

Zoning isn’t great anywhere, but it’s worst in the Bay Area and in New York. 75% of the economic costs of misallocated labour and lost productivity growth come from New York, San Francisco, and San Jose. Furthermore, housing might be entirely responsible for Thomas Piketty’s conclusion that we’re doomed to a spiraling cycle of inequality.

Out of all of these examples of rent-seeking, the one I feel least optimistic about is zoning. The problem with zoning is that people have bought houses at the prices that zoning guaranteed. If we were to significantly loosen it, we’d be ruining many people’s principle investment. Even if increasing home wealth represents one of the single greatest sources of inequality in our society and even if it is exacting a terrifying toll on our economy, it will be extremely hard to build the sort of coalition necessary to break the backs of municipalities and local landowners.

Until we figure out how to do that, I’m going to continue to fight back tears every time I see a sign like this one:

How do we fight rent-seeking?

Surprisingly, most of the suggestions Lindsey and Teles put forth are minor, pro-democratic, and pro-government. There isn’t a single call in here to restrict democracy, shrink the size of the government, or completely overhaul anything major. They’re incrementalist, pragmatic, and give me a tiny bit of hope we might one day even be able to conquer zoning.

Rent-seeking is easiest when democracy is opaque, when it is speedy, when it is polarized, and when it is difficult for independent organizations to supply high-quality information to politicians.

One of the right-wing policies that Lindsey and Teles are harshest on are efforts to slash and burn the civil service. They claim that this has left the civil service unable to come up with policies or data of its own. They’re stuck trusting the very people they seek to regulate for any data about the effects of their regulations.

Obviously, there are problems with this, even though it doesn’t seem to extend to outright horse-trading or data-manipulation. It’s relatively easy to nudge peoples’ decision making by choosing how data is presented. Just slightly overstate the risks and play down the benefits. Or anchor someone with a plan you know they’re primed to like and don’t present them any alternatives that would hurt your bottom line. No briefcases of money change hands, but government is corrupted nonetheless9.

To combat this, Lindsey and Teles suggest that all committees in the US House and Senate should have a staffing budget sufficient to hire numerous staffers, some of whom would work for the committee as a whole and others who would work for individual members. Everything would get reshuffled every two years, with a rank-match system used to assign preferences. Employee quality would be ensured by paying market-competitive salaries and letting go anyone who was too-consistently ranked low.

(Better salaries would also end the practice of staffers going to work for lobbyists after several years, which isn’t great for rent-seeking.)

Having staff assigned to committees, rather than representatives on a permanent basis prevents representatives from diverting these resources to their re-election campaigns. It also might build bridges across partisan divides, because staff would be free from an us vs. them mentality.

The current partisan grip on politics can actually help rent-seeking. Lindsey and Teles claim that when partisanship is high, party discipline follows. Leaders focus on what the party agrees on. Unfortunately, neither party is in any sort of agreement with itself about combatting rent-seekers, even though fighting rent-seeking offers a compelling way to spur economic growth (ostensibly a core Republican priority) and decrease economic inequality (ostensibly a core Democratic priority).

If partisanship was less severe and the coalitions less uniform, leaders would have less power over their caucuses and representatives would search for ways to cooperate across the aisle whenever doing so could create wins for their constituents. This would mark a return to the “strange-bedfellows” temporary coalitions of bygone times. Perhaps one of these coalitions could be against rent-seeking10?

Lindsey and Teles also call for more issues to be decided in general jurisdictions where public interest and opportunity for engagement are high. They point to studies that show teachers can extract rents when budgets are controlled by school boards (which are obscure and easily dominated by unions). When schools are controlled by mayors, it becomes much harder for rents to be extracted, because the venue is much broader. More people care about and vote for municipal representatives and mayors than attend school board meetings.

Similarly, they suggest that we should very rarely allow occupation licensing to be handled by the profession itself. When a professional licensing body stacked with members of the profession decides standards, they almost always do it for their own interest, not for the interest of the broader public. State governments, one the other hand, are better at considering what everyone wants.

Finally, politics cannot be too quick. If it’s possible to go from drafting a bill to passing it in less time than it takes to read it, then it’s obviously impossible to build up a public pressure campaign to stop any nastiness in it. If bills required one day of debate for every hundred pages in them and this requirement (or a similar one) was inviolable, then if someone buried something nasty in it (say, a repeal of a nation’s prevailing currency standards), people would know, would be able to organize, and would be able to make the electoral consequences of voting for it clear to their representatives.

To get to a point where any of this is possible, Lindsey and Teles suggest building up a set of policies on the local, state, and national levels and working to build public support for them. With these policies existing in the sidelines, it will be possible to grab any political opportunity – the right scandal or outrage, perhaps – and pressure representatives to stand up against entrenched interests. Only in these moments when everyone is paying attention can we make it clear to politicians that their careers depend most on satisfying our desires than they do on satisfying the desires of the people who fund their campaign. Since these moments are rare, preparation for them is key. It isn’t enough to start looking for a solution when an opportunity presents itself. If we don’t move quickly, the rent-seekers will.

This book is, I think, the opening salvo in this war. Its slim and its purpose is to introduce people from across the political spectrum to the problem of rent-seeking and galvanize them to prepare for when the time is right. Its’ authors are high profile economists with major backing. Perhaps this is also a signal that similar backing might be available for anyone willing to innovate around anti-rent-seeking policy?

For my part, I had opposed rent-seeking because I knew it hurt economic growth. I hadn’t understood just how much it contributed to income inequality. Rent-seeking increases corporate profits, making capitalists far wealthier than labourers can ever hope to be. It inflates the salaries of already wealthy professionals at the cost of everyone else and locks people without college degrees out of all but the most moribund or dangerous parts of the job market. It leads bankers to speculate wildly, in a way that occasionally brings down the economy. And it makes the humble home-owners of last generation the millionaires of this one, while pricing millions out of what was once a rite of passage.

Lindsey and Teles convinced me that fighting rent-seeking is entirely consistent with my political commitments. Municipal elections are coming up and I’m committed to finding and volunteering for any candidate who is consistently anti-zoning. If none exists, then I’ll register myself. Winning almost isn’t the point. I want to be one of those people getting the word out, showing that alternatives to the current broken system is possible.

And when the time is right, I want to be there when those alternatives supplant the rent-seekers.

-

Rent-seeking doesn’t necessarily have to lead to increased inequality. Strict immigration controls, monopolies, strong unions, and strict tariffs all extract rents. These rents, however, tend to distribute down or sideways, so don’t really increase inequality. ↩

-

Banks don’t keep enough money on hand to cover deposits entirely, because they need to lend out money to make money. If banks didn’t lend money, you’d have to pay them for the privilege of parking your money there. This means that banks run into a problem when everyone tries to withdraw their money at once. Eventually, there will be no more money and the bank will fail. This used to happen all the time.

Before deposits were insured, it was only rational to withdraw your money if you thought there was even a small chance of a bank run. If you didn’t withdraw your money from a bank without deposit insurance and a bank run happened, you would lose your whole deposit.

Bank architecture reflects this risk. Everything about the imposing facades of old banks is supposed to make you think they’re as stable as possible and so feel comfortable keeping your money there. ↩ -

Socialists. ↩

-

The rise of streaming and torrenting suggests that this is more often held as an abstract principle than it is followed “in the breach”. ↩

-

See also his argument for why we shouldn’t retroactively grant new exclusivity on generics. ↩

-

I wonder if this generalizes? Would a parliament full of engineers be obsessed with optimization and fond of very clear laws? Would a parliament full of doctors spend a lot of time running a differential diagnosis on the nation? Certainly military dictators excel at seeing everyone as an enemy on whom force can be justifiably used. ↩

-

College graduates in the wealthiest cities make 61% more money than college graduates in the least wealthy cities, while people with only high school degrees make 137% more in the richest cities compared to the poorest cities. This suggests that it’s possible high school graduates are much better off in wealthy cities, but it could also be true that college graduates fall prey to money illusions or are willing to pay a premium to live in a place that provides them with many more opportunities for new experiences. ↩

-

I think there will also always be social factors preventing people from moving, but perhaps these factors would weigh less heavily if real wage differences between thriving cities and declining areas weren’t driven down by inflated real estate prices in cities. ↩

-

This is perhaps the most invidious – and unintended – consequence of Stephen Harper’s agenda for Canada. Cutting the long form census made it harder for the Canadian government to enact social policies (Harper’s goal), but if these sorts of actions aren’t checked, reversed, and guarded against, they also make rent-seeking much more likely. ↩

-

In Canadian politics, I have hope that some sort of housing affordability coalition could form between some members from left-leaning parties and some principled free-marketers. Michael Chong already has a plan to lower housing prices by getting the government out of the loan securitization business. No doubt banks wouldn’t enjoy this, but I for one would appreciate it if my taxes couldn’t be used to bail out failing banks. ↩