It is a truth universally acknowledged that an academic over the age of forty must be prepared to write a book talking about how everything is going to hell these days. Despite literally no time in history featuring fewer people dying of malaria, dying in childbirth, dying of vaccine preventable illnesses, etc., it is very much in vogue to criticise the foibles of modern life. Heck, Ross Douthat makes a full-time job out of it over at the New York Times.

Enlightenment 2.0 is Canadian academic Joseph Heath’s contribution to the genre. If the name sounds familiar, it’s probably because I’ve referenced him a bunch of times on this blog. I’m very much a fan of his book Filthy Lucre and his shared blog, induecourse.ca. Because of this, I decided to give his book (and only his book) decrying the modern age a try.

Enlightenment 2.0 follows the old Buddhist pattern. It claims that (1) there are problems with contemporary politics, (2) these problems arise because politics has become hostile to reason, (3) there is a way to have a second Enlightenment restore politics to how they were when they were ruled by reason, and (4) that way is to build politics from the ground up that encourage reason.

Now if you’re like me, you groaned when you read the bit about “restoring” politics to some better past state. My position has long been that there was never any shining age of politics where reason reigned supreme over partisanship. Take American politics. They became partisan quickly after independence, occasionally featured duels, and resulted in a civil war before the Republic even turned 100. America has had periods of low polarization, but these seem more incidental and accidental than the true baseline.

(Canada’s past is scarcely less storied; in 1826, a mob of Tories smashed proto-Liberal William Lyon Mackenzie’s printing press and threw the type into Lake Ontario. Tory magistrates refused to press charges. These disputes eventually spiralled into an abortive rebellion and many years of tense political stand-offs.)

What really sets Heath apart is that he bothers to collect theoretical and practical support for a decline in reason. He’s the first person I’ve ever seen explain how reason could retreat from politics even as violence becomes less common and society becomes more complex.

His explanation goes like this: imagine that once every ten years politicians come up with an idea that helps them get elected by short-circuiting reason and appealing to baser instincts. It gets copied and used by everyone and eventually becomes just another part of campaigning. Over a hundred and fifty years, all of this adds up to a political environment that is specifically designed to jump past reason to baser instincts as soon as possible. It’s an environment that is actively hostile to reason.

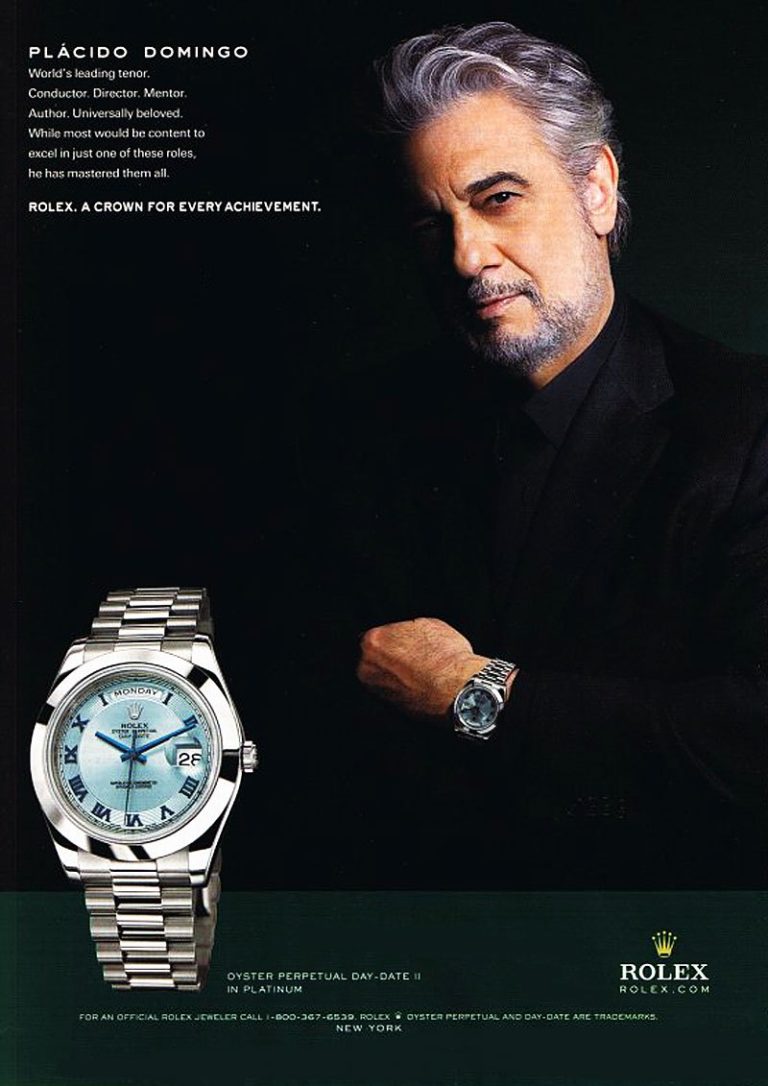

We have some evidence of a similar process occurring in advertising. If you ever look at an old ad, you’ll see people trying to convince you that their product is the best. Modern readers will probably note a lot of “mistakes” in old ads. For example, they often admit to flaws in the general class of product they’re selling. They always talk about how their product fixes these flaws, but we now know that talking up the negative can leave people with negative affect. Advertising rarely mentions flaws these days.

Modern ads are much more likely to try and associate a product with an image, mood, or imagined future life. Cleaning products go with happy families and spotless houses. Cars with excitement or attractive potential mates.

In Heath’s view, one negative consequence of globalism is that all of the most un-reasonable inventions from around the world get to flourish everywhere and accumulate, in the same way that globalism has allowed all of the worst diseases of the world to flourish.

Heath paints a picture of reason in the modern world under siege in all realms, not just the political. In addition to the aforementioned advertising, Facebook tries to drag you in and keep you there forever. “Free to play” games want to take you for everything you’re worth and employ psychologists to figure out how. Detergent companies wreck your laundry machine by making it as hard as possible to measure the right amount of fabric softener.

(Seriously, have you ever tried to read the lines on the inside of a detergent cap? Everything, from the dark plastic to small font to multiple lines to the wideness of the cap is designed to make it hard to pour the correct amount of liquid for a single load.)

All of this would be worrying enough, but Heath identifies two more trends that represent a threat to a politics of reason.

First is the rise of Common Sense Conservatism. As Heath defines it, Common Sense Conservatism is the political ideology that elevates “common sense” to the principle political decision-making heuristic. “Getting government out of the way of businesses”, “tightening our belts when times are tight”, and “if we don’t burn oil someone else will” are some of the slogans of the movement.

This is a problem because common sense is ill-suited to our current level of civilizational complexity. Political economy is far too complicated to be managed by analogy to a family budget. Successful justice policy requires setting aside retributive instincts and acknowledging just how weak a force deterrence is. International trade is… I’ve read one newspaper article that correctly understood international trade this year and it was written by Paul fucking Krugman, the Nobel Prize winning economist.

As the built environment (Heath defines this as all the technology that now surrounds us) becomes more hostile to reason (think: detergent caps everywhere) and further from what our brains intuitively expect, common sense will give us worse and worse answers to our problems.

That’s not even to talk about coordination problems. Common Sense Conservatism seems inextricably tied to unilateralism and a competitive attitude (after all, it’s “common sense” that if someone else is winning, you must be losing). With many of the hardest problems facing us (global warming, AI, etc.) being co-ordination problems, Common Sense Conservatism specifically degrades the capacity of our political systems to respond to them.

The other problem is Jonathon Haidt. In practical terms, Haidt is much less of a problem than our increasingly hostile technology or the rise of Common Sense Conservatism, but he has spearheaded a potent theoretical attack on reason.

As I mentioned in my review of Haidt’s most important book, The Righteous Mind, Heath describes Haidt’s view of reason as “essentially confabulatory”. The driving point in The Righteous Mind is that a lot of what we consider to be “reason” is in fact post-facto justifications for our actions. Haidt describes his view as if we’re the riders on an elephant. We may think that we’re driving, but we’re actually the junior partner to our vastly more powerful unconscious.

(I’d like to point out that the case for elephant supremacy has collapsed somewhat over the past five years, as psychology increasingly grapples with its replication crisis; many studies Haidt relied upon are now retracted or under suspicion.)

Heath thought (even before some of Haidt’s evidence went the way of the dodo) that this was an incomplete picture and this disagreement forms much of the basis for recommendations made in Enlightenment 2.0.

Heath proposes a modification to the elephant/rider analogy. He’s willing to buy that our conscious mind has trouble resisting our unconscious desires, but he points out that our conscious mind is actually quite good (with a bit of practise) at setting us up so that we don’t have to deal with unconscious desires we don’t want. He likens this to hopping off the elephant, setting up a roadblock, then hopping back, secure in the knowledge that the elephant will have no choice but to go the way we’ve picked out for it.

A practical example: you know how it can be very hard to resist eating a cookie once you have a packet of them in your room? Well, you can actually make it much easier to resist the cookie if you put it somewhere inconveniently far from where you spend most of your time. You can resist it even better if you don’t buy it in the first place. Very few people are willing to drive to the store just because they have a craving for some sugar.

If you have a sweet tooth, it might be hard to resist buying those cookies. But Heath points out that there’s a solution even for this. One of our most powerful resources is each other. If you have trouble not buying unhealthy snacks at the last second, you can go shopping with a friend. You pick out groceries for her from her list and she’ll do the same for you. Since you’re going to be paying with each other’s money and giving everything over to each other at the end, you have no reason to buy sweets. Do this and you don’t have to spend all week trying not eat the cookie.

Heath believes the difference between people who are always productive and always distracted has far more to do with the environments they’ve built than anything innate. This feels at least half-true to me; I know I’m much less able to get things done when I don’t have my whole elaborate productivity system, or when it’s too easy for me to access the news or Facebook. In fact, I saw a dramatic improvement in my productivity – and a dramatic decrease in the amount of time I spent on Facebook – when I set up my computer to block it for a day after I spend fifteen minutes on it, uninstalled it from my phone, and made sure to keep it logged out on my phone’s browser.

(It’s trivially easy for me to circumvent any of these blocks; it takes about fifteen seconds. But that fifteen seconds is to enough to make quickly opening up a tab and being distracted unappealing.)

This all loops back to talking about how the current built environment is hostile to reason – as well as a host of other things that we might like to be better at.

Take lack of sleep. Before reading Enlightenment 2.0, I hadn’t realized just how much of a modern problem this is. During Heath’s childhood, TVs turned off at midnight, everything closed by midnight, and there were no videogames or cell phones or computers. Post-midnight, you could… read? Heath points out that this tends to put people to sleep anyway. Spend time with people already at your house? How often did that happen? You certainly couldn’t call someone and invite them over, because calling people after midnight doesn’t discriminate between those awake and those asleep. Calling a land line after midnight is still reserved for emergencies. Texting people after midnight is much less intrusive and therefore much politer.

Without all the options modern life gives, there wasn’t a whole lot of things that really could keep you up all night. Heath admits to being much worse at sleeping now. Video games and online news conspire to often keep him up later than he would like. Heath is a professor and the author of several books, which means he’s a probably a very self-disciplined person. If he can’t even ignore news and video games and Twitter in favour of a good night’s sleep, what chance do most people have?

Society has changed in the forty some odd years of his life in a way that has led to more freedom, but an unfortunate side effect of freedom is that it often includes the freedom to mess up our lives in ways that, if we were choosing soberly, we wouldn’t choose. I don’t know anyone who starts an evening with “tonight, I’m going to stay up late enough to make me miserable tomorrow”. And yet technology and society conspire to make it all too easy to do this over the feeble objections of our better judgement.

It’s probably too late to put this genie back in its bottle (even if we wanted to). But Heath contends it isn’t too late to put reason back into politics.

Returning reason to politics, to Heath, means building up social and procedural frameworks like the sort that would help people avoid staying up all night or wasting the weekend on social media. In means setting up our politics so that contemplation and co-operation isn’t discouraged and so that it is very hard to appeal to people’s base nature.

Part of this is as simple as slowing down politics. When politicians don’t have time to read what they’re voting on, partisanship and fear drive what they vote for. When they instead have time to read and comprehend legislation (and even better, their constituents have time to understand it and tell their representatives what they think), it is harder to pass bad bills.

When negative political advertisements are banned or limited (perhaps with a total restriction on election spending), fewer people become disillusioned with politics and fewer people use cynicism as an excuse to give politicians carte blanche to govern badly. When Question Period in parliament isn’t filmed, there’s less incentive to volley zingers and talking points back and forth.

One question Heath doesn’t really engage with: just how far is it okay to go to ensure reason has a place in politics? Enlightenment 2.0 never goes out and says “we need a political system that makes it harder for idiots to vote”, but there’s a definite undercurrent of that in the latter parts. I’m also reminded of Andrew Potter’s opposition to referendums and open party primaries. Both of these political technologies give more people a voice in how the country is run, but do tend to lead to instability or worse decisions than more insular processes (like representative parliaments and closed primaries).

Basically, it seems like if we’re aiming for more reasonable politics, then something might have to give on the democracy front. There are a lot of people who aren’t particularly interested in voting with anything more than their base instincts. Furthermore, given that a large chunk of the right has more-or-less explicitly abandoned “reason” in favour of “common sense”, aiming to increase the amount of “reason” in politics certainly isn’t politically neutral.

(I should also mention that many people on the left only care about empiricism and reason when it comes to global warming and are quite happy to pander to feelings on topics like vaccines or rent control. From my personal vantage point, it looks like left-wing political parties have fallen less under the sway of anti-rationalism, but your mileage may vary.)

Perhaps there’s a coalition of people in the centre, scared of the excess of the extreme left and the extreme right that might feel motivated to change our political system to make it more amiable to reason. But this still leaves a nasty taste in my mouth. It still feels like cynical power politics.

While there might not be answers in Enlightenment 2.0 (or elsewhere), I am heartened that this is a question that Heath is at least still trying to engage with.

Enlightenment 2.0 is going to be one of those books that, on a fundamental level, changes how I look at politics and society. I had an inkling that shaping my environment was important and I knew that different political systems lead to different strategies and outcomes. But the effect of Enlightenment 2.0 was to make me so much more aware of this. Whenever I see Google rolling out a new product, I now think about how it’s designed to take advantage of us (or not!). Whenever someone suggests a political reform, I first think about the type of discourse and politics it will promote and which groups and ideologies that will benefit.

(This is why I’m not too sad about Trudeau’s broken electoral reform promises. Mixed member proportional elections actually encourage fragmentation and give extremists an incentive to be loud. First past the post gives parties a strong incentive to squash their extremist wings and I value this in society.)

For that (as well as its truly excellent overview of all the weird ways our brains evolved), I heartily recommend Enlightenment 2.0.