Breaking news: a retired mechanic spent one afternoon and $550 building a staircase. This is news because the City of Toronto said it would cost $65,000 for them to do it. They’ve since walked back that estimate, claiming it won’t be that expensive (instead, the final cost looks to be a mere $10,000).

Part of this is materials and labour. The city will probably go for something a bit more permeant than wood – probably concrete or metal – and will probably have higher labour costs (the mechanic hired a random guy off the street to help out, which is probably against city procurement policy). But a decent part (perhaps even the majority) of the increased costs will be driven by regulation.

First there’s the obvious compliance activities: site assessment, community consultation, engineering approval, insurance approval. Each of these will take the highly expensive time of highly skilled professionals. There’s also the less obvious (but still expensive and onerous) hoops to jump through. If the city doesn’t have a public works crew who can install the stairs, they’ll have to find a contractor. The search for a contractor would probably be governed by a host of conflict of interest and due diligence regulations; these are the sorts of thing a well-paid city worker would need to sink a significant amount of time into managing. Based on the salary information I could find, half a week of a city bureaucrat’s time already puts us over the $550 price tag.

And when the person in charge of compliance is highly skilled, the loss is worse than simple monetary terms might imply. Not only are we paying someone to waste her time, we are also paying the opportunity cost of her wasting her time. Whenever some bright young lawyer or planner is stuck reading regulatory tomes instead of creating something, we are deprived of the benefits of what they could have created.

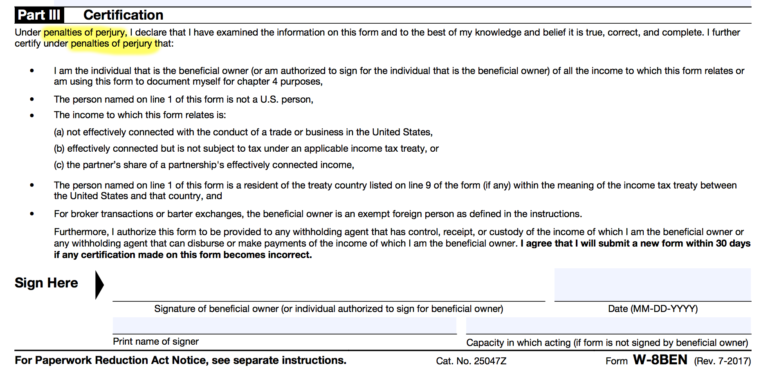

When it comes to the stairs, regulations don’t stop with our hypothetical city worker. The construction firm they hire is also governed by regulations. They have to track how much everyone works, make sure the appropriate taxes go to the appropriate parties, ensure compliance with workplace health and safety standards and probably take care of a dozen minor annoyances that I don’t know about. When you aren’t the person doing these things, they just blend into the background and you forget that someone has to spend a decent part of their time filling out incredibly boring government forms – forms that demand accuracy under pain of perjury.

Hell, the very act of soliciting bids can inflate the cost, because each bid will require a bunch of supporting paperwork (you can’t submit these things on a sticky note). As is becoming the common refrain, this takes time, which costs money. You better bet that whichever firm eventually gets hired will roll the cost of all its failed past bids (either directly or indirectly) into the cost the city ends up paying.

It’s not just government regulations that drive up the price of stairs either. If the city has liability insurance, it will have to comply with a bunch of rules given to it by its insurer (or face higher premiums). If it chooses to self-insure, the city actuaries will come up with all sorts of internal policies designed to lessen the city’s chance of liability – or at least lessen the necessary payout when the city is inevitably sued by some drunk asshole who forgets how to do stairs and breaks a bone.

With all of this regulation (none of which seems unreasonable when taken in isolation!) you can see how the city was expecting to shell out $65,000 (at a minimum) for a simple set of stairs. That they managed to get the cost down to $10,000 in this case (to avoid the negative media attention of over-estimating the cost of stairs more than one hundred times over?) is probably indicative of city workers doing unpaid overtime, or other clever cost hiding measures1.

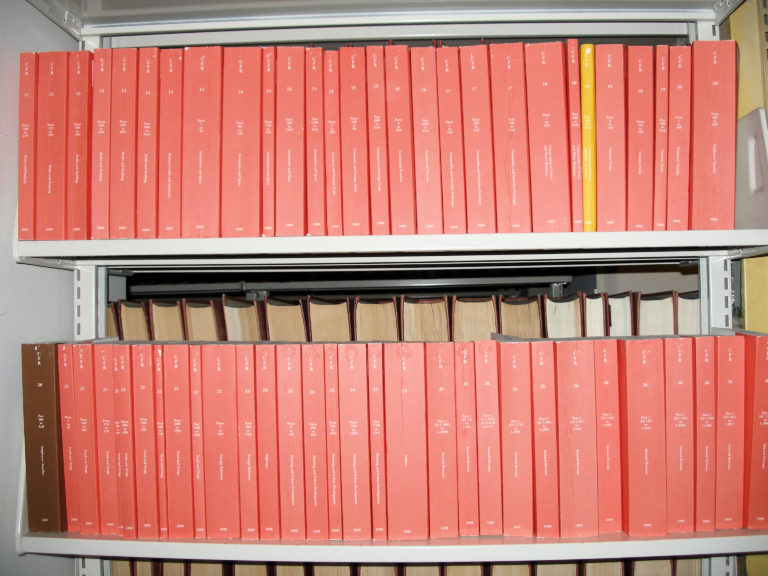

The point here is that regulation is expensive. It’s expensive everywhere it exists. The United States has over 1,000,000 pages of federal regulation. Canada makes its federal regulation available as a compressed XML dump(!) with a current uncompressed size of 559MB. Considering XML overhead, the sum total of Canadian federal regulation is probably approximately equivalent to that of the United States.

This isn’t it for either country; after federal regulation, there’s provincial/state and local regulations. Then there are the interactions between all three, with things becoming even worse when you want to do anything between different jurisdictions within a country or (and it’s a miracle this can even happen at all) between countries.

People who can hold a significant subset of these regulations in their head and successfully navigate them (without going mad from boredom) are a limited resource. Worse, they’re a limited resource who can be useful in a variety of fields (i.e. there has to be some overlap between the people who’d make good programmers, doctors, or administrators and the people who can parse and memorize reams of regulation). Limited supply and consistent (or increasing) demand drives the excessive cost of buying their time that I mentioned earlier.

This is the part where I’m supposed to talk about how regulation destroys jobs and how we should repeal it all if we care about the economic health of our society. But I’m not going to do that. The idea that regulation kills jobs is based on economic fallacies2 and not borne out by evidence (although it is surprisingly poorly studied and new evidence could change my mind here).

As best we can currently tell, regulation doesn’t destroy jobs; it shifts them. In a minimally regulated environment, there will be fewer jobs requiring highly educated compliance wizards and more jobs for everyone else. As the amount of regulation increases, we should see more and more labour shift from productive tasks to compliance tasks. Really regulation is one of the best ways that elites can guarantee jobs for other elites.

Viewed through this lens, regulation is similar to a very regressive tax. It might be buying us social goods that we really want, but it does so in a way that transfers wealth from already disadvantaged workers to already advantaged workers. I think (absent offloading regulatory compliance onto specialized AI expert systems) that this might be an inherent feature of regulation.

When I see progressives talking about regulation, the tone is often that companies should whine about it less. I think it’s totally true that many companies push back against regulation that is (on the face of it at least) in the public good – and that companies aren’t pushing back primarily out of concern for their workers. However, rejecting the libertarian position doesn’t mean we should automatically support all regulation. After reading this, I hope you look at regulation as a problematically regressive tax that can have certain other benefits.

Because even taking into account its regressive effects, regulation is often a net good. Emissions standards around nitrous oxide emissions have saved thousands of lives – and Volkswagen cheating on them will lead to the “pre-mature deaths” of over one thousand people.

Corporations have no social duty beyond giving returns to their shareholders. It’s only through regulation that we can channel them away from anti-social behaviour3. Individuals are a bit better, motivated as they are by several things beyond money, but regulation is still sometimes needed to help us avoid the tragedy of the commons.

That said, even the best-intentioned regulation can have ruinous second order effects. Take the new French law that requires supermarkets to donate unsold, expiring produce to food banks. The law includes a provision indemnifying supermarkets against any legal action for food poisoning or other problems caused by the donated food. Without that provision, companies would be caught in a terrible bind. They’d face fines if they didn’t donate, but face the risk of huge lawsuits if they did45.

Regulation isn’t just the purview of the government. If all government regulation disappeared overnight, private regulation – overseen primarily by insurance companies – would take its place. The ubiquity of liability insurance in this litigious age has already turned many insurers into surrogate regulators6.

Insurance companies really hate paying out money. They can only make money if they make more in premiums than they pay out for losses. The loss prevention divisions of major insurers work with their clients, making sure they toe the line of the insurer’s policies and raising their premiums when they don’t.

This task has become especially important for the insurers who provide liability insurance to police departments. Many local governments lack the political will to rein in their police force when they engage in misconduct, but insurance companies have no such compunctions. Insurers have written use of force policies, provided expensive training, furnished use of force simulators, and ordered the firing of chiefs and ordinary officers alike.

When insurers make these demands, they expect to be obeyed. Cross an insurer and they’ll withdraw insurance or make the premiums prohibitively high. It isn’t unheard of for police departments to be disbanded if insurers refuse to cover them. Absent liability insurance, a single lawsuit can literally bankrupt a small municipality, a risk most councillors won’t take.

As the Colombia Law School article linked above suggested, it may be possible to significantly affect the behaviour of insurance purchasers with regulation that is targeted at insurers. I also suspect that you can abstract things even further and affect the behaviour of insurers (and therefore their clients) by making arcane changes to how liability works. This has the dubious advantage of making it possible to achieve political goals without obviously working towards them. It seems likely that it’s harder to get together a big protest when the aim you’re protesting against is hidden behind several layers of abstraction7.

Regulation isn’t inherently good or bad. It should be able to stand on its own merits and survive a cost-benefit analysis. This will inevitably become a tricky political question, because different people weight costs and benefits differently, but it isn’t an intractable political problem.

(I know that’s what I always say. But it’s a testament to the current political climate that saying “policy should be based on cost-benefit analyses, not ideology” can feel radical8.)

I would suggest that if you’re the type of person whose knee-jerk response to regulation is to support it, you should look at how it will displace labour from blue-collar to white-collar industries or raise prices and ponder if this is worth its benefits. If instead you oppose regulation by default, I’d suggest looking at its goals and remembering that the cost of reaching them isn’t infinite. You might be surprised at what a true cost benefit analysis returns.

Also, it probably seems true that some things are a touch over-regulated if $65,000 (or even $10,000) is an unsurprising estimate for a set of stairs.

Epistemic Status: Model

-

Of course, even unpaid overtime has a cost. After a lot of it, you might feel justified to a rather longer paid vacation than you might otherwise take. Not to mention that long hours with inadequate breaks can harm productivity in the long run. ↩

-

It seems to rest on the belief that regulation makes things more expensive, therefore fewer people buy them, therefore fewer people are needed to produce them. What this simple analysis misses (and what’s pointed out in the Pro Publica article I linked) is that regulatory compliance is a job. Jobs lost directly producing things are more or less offset by jobs dealing with regulations, such that increased regulation has an imperceptible effect on employment. This seems related to the lump of labour fallacy, although I’ve yet to figure out how to clearly articulate the connection. ↩

-

In Filthy Lucre, Professor Joseph Heath talks about the failures of state-run companies to create “socially inclusive growth”. Basically, managers in companies care far more about their power within the company than the company being successful (the iron law of institutions). If you give them a single goal, you can align their incentives with yours and get good results. Give them two goals and they’ll focus on building up their own little fief within the company and explaining away any failures (from your perspective) as the necessary results of balancing their dual tasks (“yes, I posted no profits, I was trying to be very socially inclusive this quarter”).

Regulation, if set up so that it seriously affects profits (or if set up so that it has high personal consequences for managers) forces the manager to avoid acting in a ruinously anti-social way without leaving them with the sort of divided loyalties that can cause companies to become semi-feudal. ↩ -

The end game would quite possibly involve supermarkets setting up legally separate (with significant board overlap) charitable organizations that would handle the distribution, and compelling these shells (who would carry almost no cash so as to be judgement proof) to sign contracts indemnifying the source supermarket against all lawsuits. This would require lots and lots of lawyer time and money, which means consumers would see higher food prices. ↩

-

Actually, higher food prices are pretty much inevitable, because there’s still a bunch of new logistics that have to be worked out as a result of this law. If the logistics turn out to be more expensive then the fines, supermarkets will continue to throw out food (while passing the costs of the fines on to the consumer). If the fines are more expensive, then food will be donated (but price of donating it will still inevitably be passed on to consumers). Any government program that makes food more expensive is incredibly regressive – it’s this realization that underlies the tax-free status of unprepared food in Canada.

Supplemental nutrition programs (AKA “food stamps”) have the benefit of subsidizing food for those who need it from the general tax pool, which can be based on progressive taxation and mainly paid for by the wealthy.

It’s really easy to see a bunch of food sitting around and realize it could be better used. It’s really hard (and expensive) to actually handle the transport and preparation of that food. ↩ -

Meaning that a government that really wanted to reduce regulation would have to make it rather hard to sue anyone. This seems like an unlikely use of political capital and also probably in conflict with many notions of fundamental justice.

Anyway, you should look at changes to liability the same way you look at regulation. Ultimately, they may amount to the same thing. ↩ -

This is dubious because it’s inherently anti-democratic (the government is taking actions designed to be opaque to the governed) and also incredibly baroque. I’m not talking about simple changes to liability that will be intuitively understood. I’m talking about provisos written in solid legalese that tweak liability in ways that I wouldn’t expect anyone without a law degree and expertise in liability law to understand. If a government was currently doing this, I would expect that I wouldn’t know it and wouldn’t understand it even if it was pointed out to me. ↩

-

Note, crucially, that it feels radical, but isn’t. Most people who read my blog already agree with me here, so I’m not actually risking any consequences by being all liberal/centrist/neo-liberal/whatever we’re calling people who don’t toe the party line this week. ↩