ETA (October 2018): Preliminary studies from Seattle make me much more pessimistic about the effects of the Ontario minimum wage hike. I’d also like to highlight the potential for problems when linking a minimum wage to inflation.

There’s something missing from the discussion about the $15/hour minimum wage in Ontario, something basically every news organization has failed to pick up on. I’d have missed it too, except that a chance connection to a recent blog post I’d read sent me down the right rabbit hole. I’ve climbed out on the back of a mound of government statistics and I really want to share what I’ve found.

I

Reading through the coverage of the proposed $15/hour minimum wage, I was reminded that the Ontario minimum wage is currently indexed to inflation. Before #FightFor15 really took off, indexing the minimum wage to inflation was the standard progressive minimum wage platform (as evidenced by Obama calling for it in 2013). Ontario is actually aiming for the best of both worlds; the new $15/hour minimum wage will be indexed to inflation. The hope is that it will continue to have the same purchasing power long into the future.

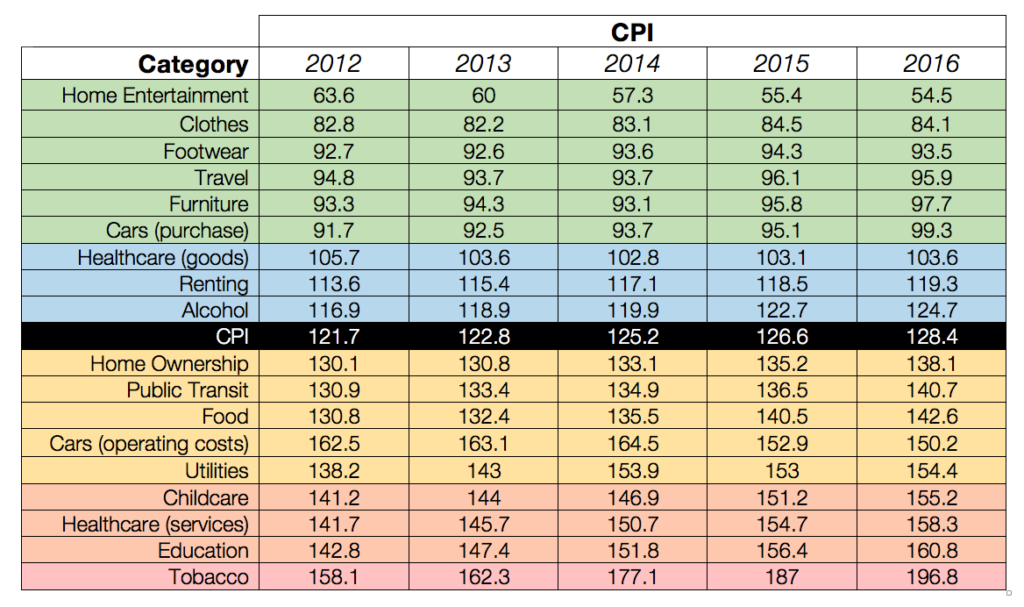

In Canada, inflation is also called the “consumer price index” or CPI. The CPI is based on a standard basket of goods (i.e. a list that includes such things as “children’s sneakers” and “French fries, curly”), which Statistics Canada assesses the price of every few months. These prices are averaged, weighted, and compared to the previous year’s prices to get a single number. This number is periodically reset to 100 (most recently in 2002). The CPI for 2016 is 128.4; in 2016, it cost $128.40 to buy a basket of goods that cost $100.00 in 2002.

The problem with the CPI is that it’s just an average; when you look at what goes into it category by category, it becomes clear that “inflation” isn’t really a single number.

Here’s the last few years of the CPI, with some of the categories broken out:

Every row in this table that is shaded green has decreased in price since 2002. Rows that are shaded blue have increased in price, but have increased slower than the rate of inflation. Economists would say that they’ve increased in price in nominal (unadjusted for inflation) terms, but they’ve decreased in price in real (adjusted for inflation) terms. Real prices are important, because they show how prices are changing relative to other goods on the market. As the real value of goods and services change, so too does the fraction of each paycheque that people spend on them.

The red, yellow, and orange rows represent categories that have increased in price faster than the general rate of inflation. These categories of goods and services are becoming more expensive in both real and nominal terms.

There’s no other way to look at the CPI that shows variation as large as that between categories. When you break it down by major city, the CPI for 2016 varies from 120.7 (Victoria, BC) to 135.6 (Calgary, AB). When you break it down by province, you see basically the same thing, with the CPI varying from 122.4 in BC to 135.2 in Alberta.

Looking at this chart, you can see that electronics (“Home Entertainment”) have become 45% cheaper in nominal (unadjusted for inflation) terms and a whopping 58% cheaper in real (adjusted for inflation) terms. Basically, electronics have never been less expensive.

On the other hand, you have education, which has become 60.8% more expensive in nominal terms and 25% more expensive in real terms. It costing more and more to get an education, in a way that can’t just be explained by “inflation”.

Three of the four categories with the biggest increases in prices rely on the labour of responsible people. The fourth is tobacco; prices increases there are probably driven by increased taxation and its position is a bit of a red herring. It’s potentially worrying that the categories where things are getting cheaper (e.g. electronics, clothes) are in the industries that are most amenable to automation. This might imply that tasks that cannot be automated are doomed to become increasingly expensive1.

II

I’m certainly not the first person to make the observation that “inflation” isn’t a single number. Economists have presumably known this forever, related as it is to the important economics concept of “cost disease”. More recently, you can see this point made from two different directions in Scott Alexander’s “Considerations on Cost Disease” (which tries to get to the bottom of the price increases in healthcare and education) and Andrew Potter’s “The age of anti-consumerism has passed” (which looks at the societal changes wrought by many consumer goods becoming much cheaper). As far as I know, no one has yet tied this observation to the discussion surrounding the new Ontario minimum wage.

Like I said above, the new minimum wage will still be indexed to inflation; the “$15/hour” minimum wage won’t stay at $15/hour. If inflation follows current trends (this is a terrible assumption but it’s all I’ve got), it will rise by about 1.5% per year. In 2020 it will be (again, bad extrapolation alert) $15.25 and in 2021 it will be $15.50.

Extrapolating backwards, the current Ontario minimum wage ($11.40/hour) was equivalent to $8.88/hour in 2002 (when the CPI was last reset). If instead of tracking inflation generally, the minimum wage had tracked electronics, it would be $4.84 today. If it tracked education, it would be $14.28. Next year, the minimum wage will be $14/hour (it will take until 2019 for the $15/hour wage to be fully phased in), which will make 2018 the first time that students working minimum wage are getting paychecks that will have increased as much as the cost of education.

This won’t last of course. The divergence in prices shows no signs of decreasing. The CPI will continue to climb upwards at a steady rate (the target is 2%, last year it only rose 1.4%), buoyed up by large increases in education costs (2.8% last year) and held down by steady decreases in the price of electronics (-1.6% last year). Imagine that the $15/hour minimum wage allows a student to pay a year’s tuition with a summer’s worth of work. If current trends continue, in 15 years, it would only cover 75% of tuition. Fifteen years after that it would cover about 60%.

III

There’s a funny thing about these numbers. The stuff that’s getting more expensive more quickly is largely stuff that younger people have to pay for. If you’re 50, have more or less raised your kids, and own a house, then you’re golden even if you’re working a minimum wage job (although by this point, you probably aren’t). Assuming your wage has increased with inflation over your working lifetime, a lot of the things you’re looking to buy (travel, electronics, medical devices) will be getting cheaper relative to what you make. Healthcare service costs (e.g. the cost of seeing a doctor) might be increasing for you in theory, but in practice OHIP has you covered for all your doctor’s visits2.

It’s younger people who are really shafted. First, they’re more likely to be earning minimum wage, with nearly 60% of minimum wage earners in Canada in the 15 to 24 age bracket. Second, the sorts of things that younger people need or aspire to (education, childcare, home ownership) are big ticket items that are increasing in cost above the rate of inflation. Like with the tuition example above, childcare and home ownership are going to slip out of the grasp of young workers even if you index their wage to inflation.

I happen to like the idea of a $15/hour minimum wage. There’s a lot of disagreement among economists as to whether they’ll be ill effects, but this meta-analysis (complete with funnel plot!) has me more or less convinced that the economy will do just fine3. Given that Ontario will still have an economy post wage-hike, I think increasing the minimum wage will be good for workers.

But a minimum wage increase leaves the larger problem of differing rates of inflation unsolved. Even with a minimum wage indexed to inflation, we’re going to have people waking up twenty-five years from now, realizing that their minimum wage job doesn’t pay for university/food/utilities/childcare/transit the same way their parents’ minimum wage job did. This will be a problem.

I’m game to kick the can down the road for a bit if it means we can make the lives of minimum wage workers better right now. But until we’ve solved this problem for good, it will keep coming back4.

-

I’m not sure this is exactly a bad thing, per se. Money is a means of signalling that you’d like your preferences satisfied. It becoming more expensive to pay actual humans to do things could mean that actual humans have so many good options that they’re only going to waste their time satisfying your preferences if you really make it worth their while. Looked at this way, this means we’re steadily freeing ourselves from work.

On the other hand, this seems to apply mainly to responsible/competent/intelligent people and not everyone is responsible/competent/intelligent, so this could also imply that we have a looming crisis, with a huge number of people simply becoming economically unnecessary. This is really bad, because high-quality life should be possible for everyone, not just those who’ve lucked into economically valuable traits and under capitalism it is really hard to have a high-quality life if you aren’t economically valuable. ↩ -

For readers outside of Ontario, OHIP is the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. It covers all hospital and clinic care for all legal residents of Ontario, as well as dental and ophthalmological care for minors. OHIP is a non-actuarial insurance program; premiums come from provincial income tax and payroll tax revenues, as well as transfer payments of federal tax revenues. All Ontarians enrolled in OHIP (i.e. basically all of us) have a health card which allows us to access all covered services free of charge (beyond the taxes we’ve already paid) any time we want to. ↩

-

No effect on the unemployment rate does not mean no effect on the employment of individual people. A $15/hour minimum wage will probably tempt some people back into the labour force (I’m thinking here that this will mostly be women), while excluding others whose labour would not be valued that highly (unfortunately this will probably hit people with certain mental illnesses or disabilities the hardest). ↩

-

I think it’s especially pernicious how the difference in inflation rates between types of goods is kind of by default a source of inter-generational strife. First, it makes it more difficult for each succeeding generation to hit the same landmarks that defined adulthood and independence for the previous generation (e.g. home ownership, education, having children), with all the terrible think-pieces, conflict-ridden Thanksgiving dinners, and crushed dreams this implies. Second, it can pit the economic interests of generations against each other; healthcare for older people is subsidized by premiums from younger ones, while the increase in the cost of homes benefit existing players (who skew older) to the determinant of new market entrants (who skew younger). ↩