Like many others who are a bit, um, obsessive when it comes to politics, I’ve long been a fan of the Political Compass. Most people are familiar with the differences between left wing redistributive and right wing capitalist politics. The observation underlying the Political Compass is that these aren’t the only salient axes of political disagreement.

In addition to the standard left-right economic disagreement, the Political Compass looks at the disagreements between libertarians and authoritarians. This second axis deals with the amount of social restrictions (or, from the other point of view, mandated social cohesiveness) a government imposes on its citizens.

The Political Compass breaks political parties (and the political views of individuals) into four quadrants: the authoritarian left (think centralized communism, e.g. Mao, Stalin), the authoritarian right (think socially conservative capitalism, e.g. Reagan, Thatcher), the libertarian right (think socially permissive capitalism e.g. Macron, Gary Johnson), and the libertarian left (socially permissive welfare states or regional collectivism, e.g. Corbyn, Stein).

It is common to see authoritarian policies coupled with deregulated capitalism and socially liberal policies coupled with more redistributive economic systems, a trend which causes many people to associate the economic left with libertarian social attitudes and the economic right with authoritarian social attitudes. One of the goals of the Political Compass is to allow people to disentangle these common correlations.

The categorization provided by the Political Compass is perhaps most useful when discussing less common political views, like nationalism and (economic) libertarianism. Many nationalists are actually very economically centrist – the nationalist and racist British National Party is economically to the left of the UK Labour Party. This makes it inappropriate to simply label these groups as “far-right”. They aren’t far right in the economic sense. They are instead very authoritarian, a characteristic most people associate with the economic right.

Libertarians are also occasionally referred to as extremely right. In this case, it is correct to make a comparison with other economically right parties, but important to remember that libertarians lack the social conservativism that defines most right-wing parties. The Libertarian Party in the United States might agree with the GOP on economics, but they’re more likely even than Democrats to oppose the militarization of police forces, the expansion of national security powers, or the war on drugs.

I’ve been a fan of the Political Compass for a long time. Recently I wondered how my political views (as measured by a political compass score) have changed over the past few years. Unfortunately, I don’t have any good records of where exactly the political compass put me in the past. All of I have to go on are my somewhat fuzzy memories, which I think put me on the extreme left-libertarian side of things (I believe the score was approximately -7/-7, far into the left-libertarian quadrant).

One of my great joys this past year has been reading year-old journal entries; this is the first time I’ve kept a regular journal, so having a written record of what exactly I did a year ago is still novel to me. Because of my journal, I’ve gained a lot of insight into how the past year has (and hasn’t) changed me. When I retook the Political Compass test recently, I was sad that I didn’t know for sure how I’d done in the past. With this in mind, I’ve decided to publish my results (and just as importantly, why I think I got them) yearly.

The Results

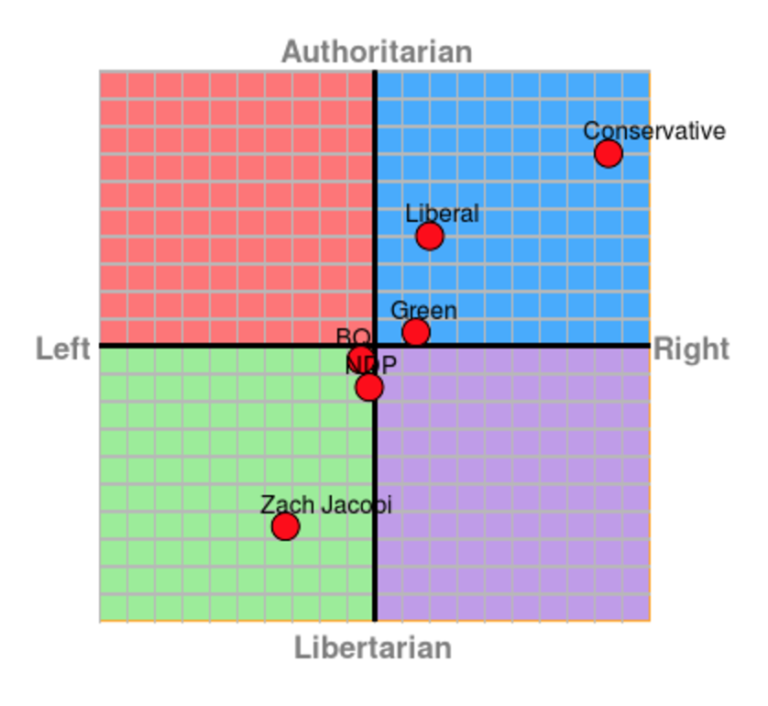

I scored -3.25 on the economic axis (this puts me firmly left of centre) and -6.56 on the authority axis (putting me deep in the social libertarian camp). Here’s how I stack up against the Canadian political parties (as assessed in 2015 by the Political Compass).

These results put me to the left of all Canadian political parties economically and very, very far from all of the Canadian political parties on civil liberties. The new score is in the same quadrant as my previous score, but is somewhat less extreme (especially economically).

Much more interesting (to my imagined version of a future me at least) than the fact of my score is the political reasoning that caused me to receive it.

Economics

I’m not surprised that the Political Compass put me more or less in the centre-left, because centre-left policies feel very much like part of my identity. Drawing on Joseph Heath’s definition, I would say that the centre-left is united by a belief that the government should primarily focus its economic interventions on solving collective action problems and fixing market failures and that the government should do this in a redistributive manner.

Adjacent to the centre-left on one side is the centre-right, which agrees with the centre-left on the purpose of government, but doesn’t advocate for redistributive solutions. One of the best examples of how this difference actually plays out is in healthcare.

The centre-left solution to the well-known market failures of health insurance is to mandate a national insurance scheme with non-actuarial premiums (premiums based on income, rather than on risk of requiring health care). The centre-right uses something like Obamacare’s individual mandate, which requires everyone to hold health insurance or pay an extra tax. In both cases market failure is corrected through government policy and the average consumer is better off. The main difference is in who picks up most of the price tag.

In general, it’s my utilitarian ethics that make me favour the centre-left over the centre-right, not a belief that one approach (or the other) leads to better economic outcomes. The utilitarian argument for progressive taxation is simple. Money has decreasing marginal utility – the more you have of it, the less each individual dollar matters to you. When dealing with essential services, I think it is most ethical to pay for them in the way that causes the least dissatisfaction, which in practice means progressive taxation.

The centre-left isn’t entirely opposed to regressive taxation though. I support regressive taxation if that’s what it takes to price an externality (e.g. carbon taxes are regressive, but another cost structure wouldn’t correctly price the externality) or if the tax leads to better outcomes (e.g. cigarette taxes are regressive, but reduce the incidence of smoking).

My disagreements with the hard-left are rarely about morality. In general, I am liable to agree with your average communist, anarcho-communist, anarcho-syndicalist, socialist, etc. about the moral necessity of reducing poverty. I disagree with the hard-left merely about what is practical or expedient. I oppose setting prices (whether it’s for rent, pharmaceuticals, or fossil fuels) because the “cure” of setting prices is so often worse than the disease the price-setting is supposed to fix. I do genuinely believe that a rising tide can lift all boats and worry that hard-left policies would sabotage the engine of growth that has lifted over billion people out of absolute poverty in the past few decades.

The main role I see for the government is offering insurance. There are a variety of insurance products that suffer from adverse selection – the tendency for only the highest risk individuals or companies to purchase insurance against for certain risks. We see adverse selection in deposit insurance1, health insurance, unemployment insurance, welfare (which is basically poverty insurance), and pensions (which are best modelled as insurance against outliving your savings). In these areas, the government can easily address a market failure by mandating that everyone must buy insurance against the risk. This lowers prices the average price considerably, making it feasable for the average person to protect against rare events in a way that isn’t possible in a market with adverse selection.

I also believe that the government should be involved in correcting for negative externalities. Without some central body forcing market participants to pay for negative externalities, we see them become distressingly common. If companies and individuals had always had to pay for the carbon they dumped into the atmosphere, we would expect global warming to be far less advanced by now. Where the externality doesn’t compete too strongly with human health and flourishing (e.g. small amounts of pollution, carbon dioxide, etc.), I think it makes sense to price it rather than ban it completely.

I absolutely loath systems like cap and trade, where a negative externality is dealt with through a complicated bureaucratic process that incentivizes people to game the system wherever possible. Just one concrete example of how this sort of thing can go wrong: a lot of the carbon credits in the European exchange came from the destruction of a potent greenhouse gas, HFC-23, at refrigerant plants in India and China. Destroying this gas became such a lucrative market that more refrigerant plants opened to get in on the action. The refrigerants were just an afterthought and were dumped on the market, making air-conditioning cheaper (which wasn’t good for global warming in its own right). When European regulators realized the scope of the mess they had caused, they banned the sale of HFC-23 carbon credits. Now former producers are threatening to release their stockpiles of HFC-23 (equivalent to two billion tonnes of CO2 emissions, 2.7 times the yearly CO2 emissions of all of Canada) unless Europe pays them off. [EDIT: An earlier version of this post said “27 times” instead of 2.7 times. I messed up the math.]

There are other reasons for my rejection of the European model of government meddling. European safety regulations do make it genuinely harder to bring new products to market in Europe (compared to the US and Canada). Here I’m happy to make a trade off that favours more innovation. Europe generously subsidizes post-secondary education. I’d prefer if we instead made post-secondary education much less mandatory.

I care about dynamism, not out of a belief in trickle-down economics, but because I’ve become (almost against my will) something of a techno-utopian. While I don’t want to diminish the role that social change plays in building a more ethical society (for example, there seems to be no technological solution to racism), I’m increasingly convinced that we won’t be able to solve poverty and disease except with radically improved technology. It’s uncontroversial to claim better technology is necessary to eradicate disease, but I think it is a bit more of an ask to get people to believe that technology offers a solution to poverty, so let me explain.

Capitalism offers an excellent solution to the problem of resource distribution: give more to people who create value for others, encouraging positive-sum interactions. But the moral case for capitalism breaks down in the presence of wealth. When people can hoard vast amounts of value or pass it on to their children (regardless of what value those children create for anyone), the argument that this method of resource allocation is ethical falls apart.

I don’t know if we can convince many people to make do with less. I know that revolutions almost always seem to go poorly and that socialism has an atrocious record of allocating even the simplest resources to people who need them – for all that there are ways global capitalism fails developing countries, global communism seemed to do no better. Given a choice between socialism and capitalism, I’ll take capitalism. It at least has the good graces to only lead to famines when they’re caused by external conditions, rather than as a matter of course [pdf link].

Given my skepticism about radical redistribution, I’ve become convinced that the only way to eradicate poverty is to create such a plenty that everyone can be guaranteed a decent living. This is why I worry about the slow and steady European approach to growth. Extreme poverty is the greatest stain on our collective morality I can see, an unconscionable and despicable ender of lives. We can’t afford to wait a single extra day to destroy it.

(In the absence of the eschaton, there is a community of people dedicated to doing what they can to reduce the impact of poverty. I encourage everyone to check out the moral case for Giving What We Can, an initiative that encourages those who can afford it to donate 10% of their income to the charities that are able to use that money to most effectively save lives).

Authority

I view the government as having little business legislating morality. I’m happy to accept economic legislation. I’m happy for the government to make activities associated with poor outcomes (e.g. alcohol consumption) more expensive via taxes. I’m even happy to pay taxes, both of the regular and “vice” varieties. I accept that taxes are a coercive use of government violence and I don’t care. I’m not a deontologist. I view violence as likely to be wrong, but I’m actually fine with the threat of violence being used to force society wide cooperation on the sorts of things that we’d mostly agree to from behind a Rawlsian veil of ignorance.

On the other hand, when we’re dealing with private, consensual behaviour (between people able to meaningfully consent), I can’t see any good that can come out of enforcing particular people’s versions of morality. I oppose most all blanket restrictions on the right of people to choose what to do with their bodies and oppose most especially restrictions on the ability of women to control their fertility. I oppose tighter restrictions on euthanasia. I oppose prohibitory drug laws (both out of a philosophical belief that people should be free to make their own decisions about their health, even bad ones, and out of a belief that prohibition increases crime and decreases access to treatment).

I even break with many other skeptics with my opposition to banning homeopathy or other widely accepted but empirically useless forms of placebo treatment. A friend has convinced me we’d likely see worse outcomes if we forced alternative medicines and their practitioners underground.

I think Canada’s free speech protections are inadequate and that we’re at risk of becoming a forum for libel shopping. I’ve become increasingly convinced that the only proper response to most speech is more speech, not violence (even state sanctioned violence, like arrest and imprisonment). I make an exception here only for credible threats (in the context of internet discussion, a credible threat is something like: “I will be waiting at __, the place you work tomorrow and I’ll have a bullet with your name on it”, not “fuck you, I’m going to kill you”).

I think violent or hateful speech clearly marks someone as an unpleasant person to be around. Freedom of speech is inextricably tied to freedom of association; free speech rights can’t protect you from the social or reputational consequences of your speech. If you stop being invited to anything because of odious things you’ve said, you deserve it. No one has to offer you a platform for your speech. I see no responsibility to invite controversial speakers to events; doing so doesn’t “stand up for free speech”. Standing up for free speech merely requires we oppose violent responses to speech (including credible threats in response to speech) made by any actors, even the state.

Free speech is just one example of a right that is constantly under threat. Fair trials, access to housing without discrimination, and equal treatment under the law are arguably more important. I do support a central government enshrining rights and protecting people’s ability to enjoy these rights. The best quick heuristic I have for telling the difference between rights and legislated morality is that rights enumerate activities you should always be allowed to do, while legislated morality enumerates activities you will never be allowed to do.

I wish it was easier to tell when one person’s right becomes another person’s restriction. For me this feels intuitively simple, but maddeningly difficult to systematize. If you have a system, please share it with me. It will probably end up in my post next year.

My social libertarian streak comes from my belief in precedent utilitarianism. Precedent utilitarianism is basically a hybrid of rule and act utilitarianism. It acknowledges that many actions, especially those by taken by our government and leaders, set precedents that other people follow. Precedents you set are always transformed to the axioms of the people who witness them being set. If Prime Minister Trudeau were to remove a Supreme Court justice for being too conservative, the precedent he would be setting for future for conservative prime ministers wouldn’t be “it is okay to remove judges that are dangerously behind the times” (even if that was Trudeau’s explicit intention), it would be “it is okay to remove judges I disagree with”. I feel like the only way to avoid a horrible yo-yo of morality laws is to leave private morality as a private matter and respect that people have a variety of different beliefs and values.

I think that precedent utilitarianism looks favourable on human rights laws and I think Canada has an unusually good set of protected characteristics. I disagree with libertarians who find the human rights codes an unacceptable check on freedoms. I’m glad we have a set of protected characteristics that both protect vulnerable people from direct harm and protect society from tit-for-tat retaliation as various in-groups are threatened.

I do sometimes find my support for protected characteristics hard to square with my firm belief that the government shouldn’t enforce morality. I think that the precedent utilitarian argument for a government that doesn’t legislate morality but does vigourously enforce rights, including protection from discrimination, is probably best summed up by Scott Alexander in the essay In Favour of Niceness, Community, and Civilization. When the government stands up for rights, it is reminding people that they will be much better off if they avoid negative sum exchanges (like reciprocal discrimination) and instead focus on positive sum exchanges.

Delta

The change since I last took this test (2-3 years ago) is about +4 on the economic axis and +0.5 on the libertarian axis.

I think the change on the authoritarian/libertarian axis is driven by my increasing patriotism. All government is composed of trade-offs. I am such a product of the Canadian trade-offs that I could not countenance living long term (or raising children) in a country other than Canada.

Changes on the economic axis were driven by my changing opinions about socialism. A few years ago my thoughts were: “maybe this could work”. My current thoughts are more: “socialism: the correct answer for the post-scarcity future, where its propensity for famines will no longer be a problem”. A combination of In Due Course and Slate Star Codex convinced me that capitalism is our best bet for getting to that post-scarcity future.

Predictions

Looking directly at my current positions themselves, I don’t expect them to change much over the next year. Given that I recall feeling that way last time I took this test, I’m inherently skeptical of that intuition.

Taking just the past into account, I should expect my positions to change regardless of how I feel about them. Taking everything into account, here’s where I think I will be at the end of May 2018:

- I will have an economic score > -2.25: 50%

- I will have an economic score > -4.25: 80%

- My top level economic identity will still be "capitalist": 80%

- I will have an authority score > -7.56: 70%

- I will have an authority score < -5.56: 90%

- My top level social identity will still be "libertarian": 90%

-

Bank runs used to be a fact of life. Whenever anyone got hint of any trouble at a bank, they’d rush to it and pull all of their money out, to protect against losing it in the event the bank failed. Unfortunately, this often caused banks to fail, because everyone had an incentive to try and pull all their money out at the slightest hint of insecurity. If they didn’t, they’d risk losing it when other people ran to the bank to do the same. Old banks are imposing to give people a sense that their money is safe there. Ever wondered why bank runs just stopped happening in developed countries? Turns out it’s because the government started to insure deposits. Once you know that your money will be safe no matter what, you no longer have any incentive to withdraw it at the first sign of trouble. ↩