In an effort to make my nuclear weapons post series a one stop resource for anyone interested in getting up to speed on nuclear weapons, I’ve decided to add supplementary materials filling any gaps that are pointed out to me. This supplementary post is on laser enrichment.

Enrichment is one of the more difficult steps in the building of certain nuclear weapons. Currently, enrichment is accomplished through banks of hundreds or thousands of centrifuges, feeding their products forward towards higher and higher enrichment percentages.

Significant centrifuge plants are relatively big (the Natanz plant in Iran covers 100,000m2, for example) and require a large and consistent supply of energy, which often makes it possible spot them in satellite imagery. The centrifuges themselves require a recognizable combination of components, which are carefully monitored. If a nation were to suddenly buy up components implicated in centrifuge design, it would clearly signal its intention to increase its enrichment capacity.

Recently, laser enrichment has emerged as an additional vector for proliferation. Properly called SILEX (separation of isotopes by laser excitation), this new technology has the potential to make enrichment (and therefore proliferation easier). This post discusses how laser enrichment works and puts the threat it represents in context. It’s both a summarization (and simplification) of the recent paper on laser enrichment in published in Science & Global Security by Ryan Snyder and the product of my extensive background reading on nuclear weapons.

How It Works

Like gas centrifugation, laser enrichment requires gaseous uranium hexafluoride (Hex). While the preparation of uranium hexafluoride doesn’t represent a significant technical challenge (compared to all of the rest of the work of building a nuclear weapon), it’s still the sort of work that most reasonable chemists try to avoid. “Requires work with a poisonous, corrosive, radioactive gas” will never be a selling feature of enrichment work.

Laser enrichment also requires a large laser capable of outputting 10.2µm light (which must be converted to 16µm using Raman scattering off of H2 gas), capable of pulsing 30,000 times per second. This appears to be just barely possible with current technology and impossible with off the shelf technology. It’s the sort of thing that would have to be custom assembled.

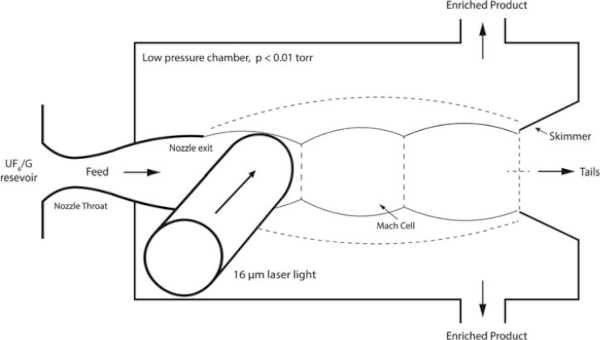

Also requiring custom assembly is the enrichment cell, which must have a nozzle capable of injecting a supersonic stream of uranium hexafluoride in such a way as to minimize post-injection expansion. The cell also must have an optically transparent window for your laser to shine through and must have several egress lines – peripheral ones for enriched product and a central one for the jet to flow out of.

Finally, if you want to make this maximally efficient, you’re going to need a mirror set up so as to have your laser pass through the gas twice. This corrects for the circular shape of the laser. Without this mirror, you won’t have enough coverage at that edges of the gas and you’re only going to operate at 78.5% of the maximum efficiency.

The whole setup looks like this:

Once you’ve assembled all of this, you’re good to start enriching.

Remember, natural Hex is largely made up of 238UF6 and is only about 0.7% 235UF6. The purpose of enrichment is to increase the percentage of 235UF6 in the gas until it is almost entirely made up of this isotope of uranium.

The process SILEX uses to achieve this is relatively simple. You run the Hex and a carrier gas (the paper says SF6) through this system at supersonic speeds and low temperatures while pulsing the laser so as to hit the jet just as it leaves the nozzle. If you’ve tuned your wavelength as directed, then photons from the laser will kick any 235UF6 molecules they hit into a heightened vibrational state (called the v3 vibrational mode), while doing nothing to the 238UF6 molecules that make up most of the Hex.

235UF6 in the v3 vibrational mode will eventually revert to a lower energy (or “ground”) state, but it is unlikely to spontaneously revert to a ground state during the few milliseconds it takes to traverse the cell. For the purposes of SILEX, 235UF6 in the v3 vibrational mode will remain in that mode unless something acts on it to change it. To improperly anthropomorphize a particle for a second, this is “bad” for the excited 235UF6, because it “wants” to be at a lower ground state.

The excited 235UF6 could get external “help” from a collision with 238UF6 (this collision would allow it to release a photon and revert to its ground state), but this is unlikely if you keep the overall concentration of UF6 in the carrier gas low (the paper recommends 5%). This is in fact exactly what is done, because efficiency is maximized when 238UF6 doesn’t get a chance to collide with 235UF6.

When you put Hex in a carrier gas like SF6, you’re going to see the formation of transitory dimers. These are temporary, weak bonds between one Hex molecule and one SF6 molecule. These bonds are fairly stable, unless the Hex is in the v3 (or similar) vibrational mode. If dimer formation occurs between v3 235UF6 and SF6, the dimer is very short-lived. The excited 235UF6 dumps all of its extra energy into the dimer bond, resulting in a lot of recoil; both the 235UF6 and the SF6 go flying apart in opposite directions. It’s the dimer formation that causes a very different outcome from a simple collision with 238UF6.

This recoil tends to push 235UF6 to the edges of the stream. A skimmer positioned around the outlet collects this enriched product. Note that it won’t be entirely enriched; the outside edges of the jet will have plenty of 238UF6 because the jet is going to be mostly 238UF6 – or at least, it will be when natural or lightly enriched uranium is the input.

If you were doing this on an industrial scale, you’d set a bunch of these cells up in series, with the enriched product of each cell being the feed for the next. In this way, you’d get the same sort of cascade towards higher enrichment as you would with centrifuges.

Proliferation

Laser enrichment might be more space and energy efficient than centrifuge arrays.

I have to say might because there’s some uncertainty here. A few key parameters that determine ease of proliferation using SILEX are missing. This isn’t because of censors removing them for security reasons. It’s because this technology is so new that there are serious question marks hanging over it. SILEX has shown promise in lab scale experiments, but there doesn’t yet exist any proof that SILEX will be superior to centrifuge enrichment when it comes to enriching uranium on an industrial scale. Given that the pilot project has been stalled since GE pulled out, it may be quite a while before we know if SELIX will fulfill its promise or not.

It looks like a SILEX would allow a country with technology on the level of Iran to enrich the same amount of uranium with only 59% of the floor area. This would make enrichment a bit easier to hide, but would do nothing to stop leaks. It was human intelligence, not satellite photos that allowed the west to discover the work at Natanz.

The error bound on SILEX energy consumption is large enough that it’s unclear if there would be a power consumption benefit or cost for rogue states switching to SILEX from indigenous centrifuge technology. State of the art American centrifuges still beat SILEX on floor space and they may beat it in energy use.

Estimates for SILEX efficiency span an order of magnitude and in the upper two-thirds of that range it seems to be a clear winner (in terms of amount of energy required per percent enrichment). I couldn’t see any consensus on the relatively likelihood of high vs. low actual efficiency, but I would personally bet that a lot of the probability distribution exists near the bottom of the allowed efficiencies. I haven’t worked in nuclear science, but I have done chemistry, and my experience is that few processes perform as well on an industrial scale as you might expect from efficiency calculations done at laboratory scale.

Enrichment with SILEX is quite possibly easier than enrichment with centrifuges. That is to say, even if SILEX doesn’t allow rogue nations to enrich more efficiently, it might allow them to enrich at all. SILEX requires some advanced optics knowledge and the lasers needed aren’t exactly available off the shelf, but they are easier to design and build than specialized enrichment centrifuges.

Before centrifugation became the preferred method of isotope separation for nuclear weapons (and nuclear energy), gaseous diffusion was used. Gaseous diffusion plants use truly prodigious amounts of space and energy. There is absolutely no way that these things can be hidden or disguised as something else.

With the advent of centrifuges, proliferation became significantly easier. Countries used to be faced with no good path to a functioning bomb. Plutonium is relatively easy to acquire and separate, but it is very difficult to build a successful implosion weapon (and impossible to do so without alerting anyone with test detonations). Uranium was relatively difficult to enrich, which closed off the option of a simpler gun assembly weapon (it is impossible to build a gun assembly weapon using plutonium).

If you want a nuclear arsenal and don’t care that gun assembly weapons are wasteful and less useful for staging, then the advent of uranium enrichment via centrifugation was a boon to you. Gun assembly weapons don’t even necessarily require test detonations, which allows for the (slim) possibility of entirely clandestine nuclear arsenals – assuming enough uranium can be secretly enriched.

SILEX may eventually exacerbate this problem, to the point where any country with access to uranium could conceivably build a relatively low yield bomb (say a dozen or two kilotons).

At present, the technology is too new for this to be true. SILEX almost certainly has a few kinks left to be worked out. Trying to work them out at the same time as your country builds a new nuclear program isn’t ideal. Best to wait for India or Pakistan to figure them out and then leak them to you in exchange for favours or missile technology (this has been North Korea’s approach to nuclear weapons and it has worked quite well).

In a decade, SILEX may make proliferation even easier. I don’t think it will make it easy to the point where Al Qaeda or Daesh can attempt to build nuclear weapons (can you imagine Daesh setting up a high-energy laser laboratory in Raqqa?). But I do worry that countries like Saudi Arabia or the Philippines might see the calculus around proliferation change enough to justify their building of a small arsenal of uranium weapons.

That would be a disaster for world peace and stability.

Governments are already reacting to threat posed by SILEX by adding necessary components to export ban and international watch lists. If any nation buys up a bunch of laser components over a short time without a good explanation, the international community will now suspect enrichment. I’m sure there are many men and women in the basement of the Pentagon and CIA headquarters now watching all laser equipment sales for more subtle signals of gradual stockpiling. Don’t think for a second that SILEX somehow represents a cheat code for proliferation. It’s still untested and unproven and governments and international organizations are already taking steps to reduce the proliferation risk.

Most nuclear technology is dual use. Uranium enrichment by centrifugation has made proliferation easier. It also increased the energy return on investment from burning uranium in power plants from ~40x to over 1500x (see here if you want to double check my calculations). Because of centrifugation, nuclear power plants could permanently end our dependence on oil if coupled with new battery technologies (and upfront capital and political will to build them).

SILEX could further increase the energy return on investment, making nuclear power plants even more economical. But SILEX also has the potential to make proliferation easier. It’s still a new, experimental technology and it might not even pan out. Until we know for sure, it is certainly best for the world to proceed with caution.