The last section required that you take it on faith that nuclear weapons are hard to design. Now it’s time to get into the nitty-gritty details of weapon design and understand why that is.

Nuclear explosions require a critical mass of the right unstable isotope. But there’s no safe way to store an assembled critical mass. As soon as you get to the critical mass, the chain reaction starts and an explosion will occur without drastic countermeasures.

All nuclear weapon design ultimately starts with this problem of assembling a critical mass in situ (and only ever in situ).

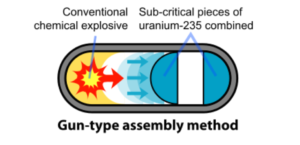

The first atomic bombs used one of two methods: gun assembly or implosion. These methods are still used to this day in fission weapons or in the fission first stage of multiple stage weapons.

4.1 Gun Assembly Design

The gun assembly method was used in Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima. In this method, sub-critical hemispheres (or a ring and a cylinder) are combined by conventional explosives into a critical mass (inside a neutron reflective tamper, which further decreases the necessary fissile mass).

This method is highly inefficient and suffers from “fizzling”. Basically, the pieces tend to become supercritical before they fully touch. The massive energy released by this reaction will then blow the pieces far apart before the reaction can complete. Only 1% of the uranium in the Hiroshima bomb was used up in the explosion. The rest was scattered and eventually rained down as fallout.

The only possible fuel in gun-assembly bombs is U-235. Plutonium fissions much more quickly, leading to the sub-critical pieces being blown apart before any significant mass of the plutonium can fission.

Due to these problems, this method has mostly fallen out of use, except in applications where only one dimension can be large (such as artillery shells).

Additional Reading: Little Boy, Nuclear Artillery, Fizzle, and Gun-type assembly weapon

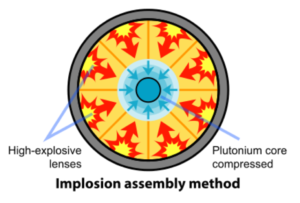

4.2 Implosion Design

Implosion type weapons start with a sub-critical mass and use explosives to compress it until it becomes critical. As the density increases, fewer neutrons escape the mass without triggering further fission events, leading to criticality despite the lower than normally necessary mass. An outer shell directly around the core that reflects neutrons can further decrease the mass necessary for a detonation.

The fizzling problem that plagues the gun-type device is also present here – eventually, the nuclear chain reaction will overwhelm the force imparted by the conventional explosives and blow the fuel apart, stopping the fission progress. Tamper design plays a factor in this; due to its very strong and heavy uranium tamper, the Fat Man plutonium bomb held together for a few hundred additional nanoseconds, allowing it to attain 20% efficiency.

In addition to tampers, there are various strategies to mitigate the breakup, all adding cost or technical complexity. For example, some nuclear weapons add a layer of aluminum-beryllium alloy between the explosives and the tamper to slow down the explosive shock wave and cause the core to be held compressed for slightly longer. This tweak can marginally increase the efficiency of a weapon.

Additional Reading: Implosion-type weapon and Fat Man

4.3 Miniaturizing Weapons

The core of a nuclear weapon is very small and relatively light (compared to conventional munitions). Most of the size and weight of a nuclear weapon comes from the explosives, tamper, and superstructure necessary to hold it all in the right place. The Fat Man bomb was egg shaped, 3.3 metres long and 1.5m in diameter at its thickest. The whole thing weighed 4.67t. the plutonium core was only 6.4kg, 0.14% of the total weight.

There’s no point having a weapon you can’t deliver. Methods that worked to deliver bombs across the 2500km that separated US island airbases and Japan weren’t feasible when dealing with the vast expanse of the Pacific, or the 8500km between the missile silos in the central United States and Moscow. Mass is the principle limit – the lighter its payload, the further a missile or bomber might fly.

Making weapons more powerful and miniaturizing them are two sides of the same coin. Every innovation that makes a bomb blast bigger can also potentially allow a smaller weapon to have the same effect as a larger weapon.

There are many unique challenges to miniaturizing weapons, such as correctly focusing explosions to create the desired pressure pattern. Regardless of the specific features necessary for miniaturization, it’s important to understand why miniaturization is such a big deal. North Korea, for example, has only possibly succeeded in miniaturizing its weapons to the point that its missiles can carry them any significant range. Until it thoroughly conquers this technical hurdle, only its closest neighbours have anything to fear.

4.4 Boosted Weapons

Boosted weapons were the first atomic bombs to make use of both fusion and fission, although they still get almost all of their energy from fission. Boosted weapons are all of the implosion type. Instead of a solid core, a boosted weapon will use a core with a hollow centre. In this hollow will be an equal mixture of tritium and deuterium.

Detonation proceeds as normal in the implosion assembly method, but with one extra wrinkle. The intense heat and pressure of the plutonium explosion compresses the deuterium/tritium mix to the point where these atoms begin to fuse into helium. Deuterium has two neutrons and one proton; tritium has three neutrons and one proton. Helium most commonly has two of each. Which means that every single fusion event also releases a neutron and imparts into that neutron a great amount of kinetic energy – it will be moving. These neutrons are the goal of the fusion stage.

Recall that fission chain reactions occur because neutrons from each fission event create further fission events. Adding a bunch of bonus neutrons to the mix puts the whole process on steroids. It helps that fusion neutrons move even faster than fission neutrons, so when they cause fission to happen, even more neutrons are released.

Using a boosted weapon, efficiency can be doubled. Which means that the same mass can give twice the yield, or the same yield can be attained with half the mass (because of this, boosting is one of the principle mechanisms of miniaturization).

There are a host of other benefits to boosting. Because the efficiency is increased, a smaller, lighter tamper can be used (these days they’re made of beryllium, which reflects neutrons but is not nearly as dense as uranium). Because the tamper is lighter, less explosives are required to compress the whole package. Boosting also gives a higher efficiency, so there’s no need for an additional focusing layer of aluminum/beryllium, leading to further savings in direct mass and mass of explosives necessary to drive the implosion.

All of these, combined with the reduction in plutonium mass necessary to get the same yield means that bombs have shrunk dramatically since the earliest days of nuclear weapons. The Fat Man bomb was 4.67t and 3.3m by 1.5m. It had a yield of 20kt. The first boosted weapon, the US “Swan” had a weight of just 47.6kg and measured 58cm long by 29.5cm in diameter, with a yield of 15kt, there was only a small loss of power for a 100x decrease in mass.

While it’s possible to build bombs in the >100kt range using boosted fission, this is rarely done. Fission remains fairly inefficient, so the amount of fissile material and tritium that must be used to get these yields quickly becomes wasteful. Very high yields remain the sole providence of fusion bombs, which can achieve these yields much more cheaply (recall how difficult and expensive enrichment is – to put a dollar value on it, the US pays $5,000 per gram of weapons grade plutonium-239).

There’s only one real drawback to boosted weapons: tritium. Tritium has a half-life of just 12 years. Even worse, it breaks down into helium-3, a form of helium with a single neutron that really “wants” to have two neutrons instead. Because of this, helium-3 “poisons” nuclear weapons by capturing neutrons that would otherwise cause fission. This means that boosted weapons must be periodically serviced and the helium-3 removed and replaced with fresh tritium. This is expensive (tritium cost $30,000 per gram in 2003 but is probably much more expensive now; we can’t calculate the cumulative cost because no government is willing to share the amount of tritium that is in each of their nukes, but it’s probably large) and almost certainly tricky (again, I can’t be sure, because no one releases their refueling procedures).

Additional Reading: Swan, Tritium, and Boosted Fission Weapon

4.5 Alarm Clock/Sloika

The Alarm Clock (named because Teller thought it would “wake up” the United States to the possibilities present by fusion weapons) or Sloika (Russian for a type of layered cake dessert) is a single stage boosted fission weapon that gets up to 20% of its yield from fusion (compare the ~1-2% that boosted weapons get from fusion).

The Sloika is made up of three layers. In the centre is a classic fission core, like in the normal implosion detonation design. Surrounding this is lithium-6 deuteride. The outer layer is unenriched uranium-238.

When this whole contraption is detonated (and detonating it takes a lot of explosives due to the three layers), three reactions occur in sequence. First, the core goes critical and fissions, ejecting a bunch of neutrons. Second, these neutrons hit the lithium-6 deuteride, which first cause lithium-6 to fission into tritium, which promptly fuses with the deuterium in the intense heat. The fusion reaction releases a lot of heat energy, a lot of radiation, and a lot of very fast neutrons. Finally, these fast fusion neutrons hit the natural uranium and cause it to fission. Since fusion neutrons are about 14 times more energetic than fission neutrons, they can cause fission even in unenriched uranium-238. The neutrons the uranium-238 releases during fission actually lack the energy to cause a self-sustaining chain reaction within itself, but they are capable of converting lithium-6 into tritium and helping the tritium fuse with deuterium. For a brief moment, this bomb has a stable multi-step chain reaction (fusion à high energy neutrons à fission à lower energy neutrons à lithium converted to tritium à fusion). Then it tears itself apart.

The Sloika derives most of its explosive power from relatively cheap natural uranium, which makes it a more cost effect way of getting yields in the 100s of kilotons compared to pure or boosted fission. It’s also safer, because most of its yield comes from a fuel incapable of spontaneous fission. Despite this it can’t truly compete with fusion weapons for cost effectiveness and lacks the ability to scale to the Mt range (as the amount of explosives necessary to detonate it grows infeasibly large at higher yields).

Because of these inadequacies, the Sloika proved a dead end in weapon design and is not used in any current nuclear weapons.

Additional Reading: Joe 4 and Alarm Clock/Sloika

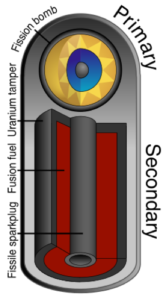

4.6 Teller-Ulam Design

The Teller-Ulam design is necessary to economically achieve multi-megaton yields with devices small enough to be delivered intercontinentally. Teller-Ulam weapons (also known as thermonuclear bombs or H-bombs) use multiple stages of fission and fusion and incorporate concepts previously seen in boosted, implosion, and Sloika weapons. Here’s what the design looks like:

The primary is a standard boosted implosion bomb, normally with a yield in the range of 10-20kt. The secondary is made up of a “sparkplug” of highly enriched plutonium or uranium, a supply of lithium-6 deuteride (the fusion fuel), and a natural or depleted uranium tamper (made primarily of uranium-238). In many designs, the bomb is also packed tightly with a plastic foam.

Detonation begins with the primary, which works exactly like the boosted implosion design described above (while boosting isn’t strictly necessary, boosting is important for reducing the size of the weapon and so in practice will be used in almost all modern thermonuclear weapons). As the primary detonates, three separate forces begin to exert immense pressure on the secondary.

First is X-ray radiation. The primary produces x-rays (in addition to neutrons and gamma rays), which can be mirrored by the outer casing to focus on the secondary. These x-rays have momentum and therefore exert pressure when they collide with the secondary. The large amount of high energy x-rays exerts a pressure equivalent to tens of millions of atmospheres, beginning the process of compression.

Plasma from the foam also plays a role in compression. X-rays aren’t just hitting the secondary. They’re also being absorbed by the foam. No plastic can withstand such an intense barrage of x-rays – so it almost immediately converts into plasma. As this plasma tries to expand in the confines of the bomb, it exerts even more pressure on the secondary, probably an order of magnitude more than the x-ray radiation alone.

Finally, the x-rays cause the tamper to begin to vaporize. Gaseous uranium boils off the surface under the intense x-ray bombardment. For every action, there must be an equal and opposite reaction and such is the case here. The uranium boiling off the surface pushes the rest of the uranium into the fusion fuel and it pushes it hard. The ablation pressure in a thermonuclear weapon is an appreciable fraction of the pressure at the centre of the sun, equivalent to many billions of Earth atmospheres.

Which one of these ultimately causes the secondary to detonate is intensely classified. What we do know is that one (or more) of these eventually causes the fissile “sparkplug” to go supercritical, which pushes on the fusion fuel from another direction and provides neutrons to activate it. Shortly after the sparkplug ignites, fusion begins.

Fusion provides a bit less than half of the total power of the average thermonuclear bomb. The rest comes from the fission of the uranium tamper with the very fast neutrons produced in the fission process.

Total yield varies from a hundred kilotons to a dozen megatons. It’s actually possible to make one bomb design that can have multiple yields (called “dial-a-yield”), by varying the amount of tritium in the primary (and therefore the pressure under which the secondary is compressed).

The Teller-Ulam design has the same disadvantage as boosted weapons: constant maintenance is required to replace the unstable tritium necessary to boost the first phase. This disadvantage pales beside the massive power of this design. It’s the only economical (in terms of cost, weight and size) way to achieve yields in the megaton range.

While a two-stage design is by far the most common, there is no theoretical cap on the number of stages this weapon can have. Each stage provides the compressive force to ignite the next. In this manner, yields up to a gigaton of TNT can be achieved, although a bomb this large would be very difficult to deliver, even with the general efficiencies of this design. The largest bomb ever detonated, the Soviet Tsar Bomba used three stages, massed 27t, and had a total yield of 50 Mt (although it used lead tampers to minimize fallout; had the tampers been uranium the yield would have been 100Mt – and fallout from the fission would have irradiated large swathes of the USSR).

Additional Reading: Thermonuclear Weapon, History of the Teller-Ulam Design, and Tsar Bomba